It’s one of life’s most frustrating ironies that Earth’s surface is over 70 percent water, but most of that is undrinkable. Desalination is an important technology that may help unlock more drinking water, and now two independent teams have developed new types of solar-powered desalination systems using very different mechanisms.

The first of the two new designs comes from researchers at MIT and Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The team says the multilayer system has an impressive overall efficiency of 385 percent, producing as much as 5.78 L (1.52 gallons) of clean water per hour per square meter of solar-collecting area, which is more than twice the amount produced by similar systems.

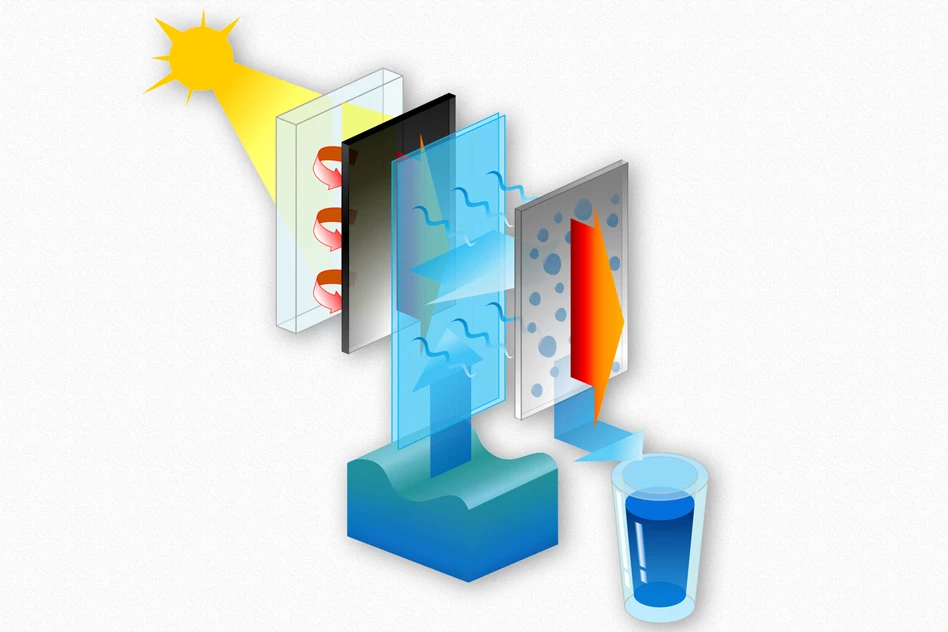

Each of the layers, arranged vertically, has an important role to play in the process. First, there’s a transparent insulating layer that lets sunlight through to a black, heat-absorbing layer. That in turn passes the heat onto several layers of wicking material, which have sucked the water up from below. The water evaporates out of that layer and strikes another surface, where it condenses and drips off to be collected.

The team says that much of the efficiency comes from the way heat is conserved. Rather than being lost to the environment, the heat gets passed along to each evaporation layer in turn. The salt is left behind in the wicking material, and apparently it’s naturally removed overnight. As the device cools down, the salt diffuses back down the material into the seawater.

The second system, designed by researchers at the University of Bath, University of Johannesburg and Bogor Agricultural University, uses a very different mechanism. Rather than moving the water through a membrane and leaving the salt behind, this device does the opposite, pulling the salt out of the water.

This feat is possible using an ionic system. Separating two chambers is a thin, synthetic, semi-permeable membrane that only allows salt ions to flow in one direction. That’s because the membrane is negatively charged, and coupled with an anionic resistor, it only allows negative ions of salt to pass through when an electric current is applied. That current doesn’t need to be too strong, and can be sourced from solar power.

When it’s switched on, salt is drawn out of the water in one chamber and deposited in a second chamber. Unlike the first system, which returns the leftover material to the sea, the team says that this salt can be collected for other uses.

The researchers on both projects say that these two designs would be useful for small-scale water desalination, possibly in portable units. That means they could be deployed in developing countries or in disaster-stricken areas, to provide drinking water when regular infrastructure is otherwise unavailable.

The MIT design is described in a paper published in the journal Energy and Environmental Science. The second study appeared in the journal Desalination, and is explained in the video below.

Sources: MIT, University of Bath