When you pull your car up on a quiet residential street at night, do you park under a street light thinking the bright light will dissuade a thief from breaking into your car? Intuitively it seems like the right thing to do, after all, it would be easier to stay unseen while stealing from a car in darkness. New research published in the Journal of Quantitive Criminology is challenging that conventional assumption, arguing rates of vehicle theft are lower in darkened streets compared to more well-lit streets.

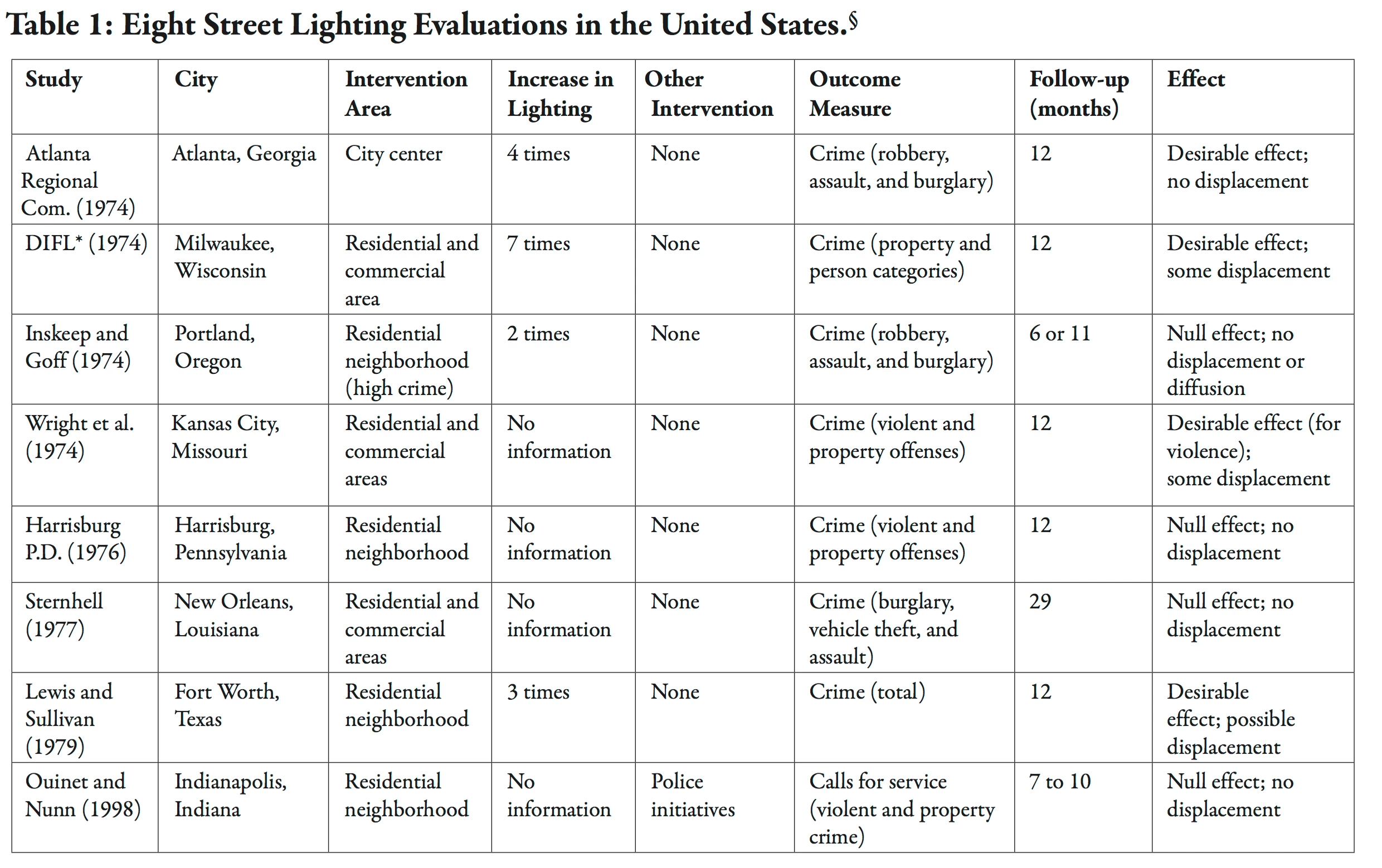

For decades researchers have been studying the association between street lighting conditions and crime. Despite years of mixed findings it is still generally believed by police, governments and citizens that improving street lighting can reduce crime.

In recent years, as a response to growing environmental concerns around energy use, many places in Europe and the United Kingdom have adopted part-night lighting schemes. The idea is to reduce the carbon footprint of a given area by automatically switching off street lights at certain times of night, often between midnight and 6am.

Of course, many people in these local communities have pushed against these part-night light plans arguing it will lead to increases in crime. Phil Edwards, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, says the new research arose out of an attempt to understand the effect of part-night light plans on crime.

“The reason we did this research is because many local authorities in the UK have introduced part-night lighting on quiet, urban residential roads and rural roads, which have very little use after midnight, to save energy costs and reduce carbon emissions,” said Edwards. “However, safety concerns about this policy have been raised.”

Back in 2015 the same research team more broadly investigated the links between different types of street lighting and crime. The study tracked several years of data spanning 62 local regions across England and Wales. No link could be found between increased violent crime or burglary and darker streets.

The new research set out to hone the prior findings, looking more closely at the impact of three kinds of street lighting on crime: part-night lighting, dimming street lights after midnight, and bright white light consistently throughout an entire night. The research also focused on smaller segments of streets to understand whether changes to lighting in one part of a street influences criminal activity in other nearby streets.

Analyzing nearly 10 years of data the researchers were able to look at what effect the institution of part-night lighting had on local crime rates. For the most part, the study replicated the team’s prior findings, detecting no link between lighting changes in a given street and levels of violence or residential burglary.

However, the interesting finding was a reduction in thefts from parked vehicles after a street introduced part-night lighting. In fact, switching off street lights at midnight led to a 50 percent drop in theft from vehicles compared to before the part-night lighting plan was introduced. Theft of vehicles was also seen to drop after part night lighting was introduced, but the researchers note this reduction was small and deemed not statistically significant.

The study also reported evidence of a kind of displacement effect where crime in one street dropped with part-night lighting but similar crime in adjacent well-lit streets increased. On average, nearby well-lit streets did show a 1.5 fold increase in theft from vehicles that coincided with the reductions of theft in part-night light streets.

But the researchers indicate not all car thefts were displaced, so there was an overall net reduction in crime. Edwards hypothesizes several reasons why crime may counter-intuitively increase on a well-lit street compared to a darkened street.

“We didn’t set out to find the reasons for the observed changes, but it is possible that when lighting is switched off after midnight, offenders consider that the costs of committing a crime, such as using a torch would likely raise suspicion among residents and risk being witnessed, outweigh the benefits,” he said. “When lighting is switched off after midnight the streets are likely to be in near darkness, which means that any would-be offenders may find it challenging to see if there are any valuable goods left unsecured in vehicles, so offenders may choose to move elsewhere to fulfil their intentions.”

The study, of course, does not broadly conclude we will all be better off if there were no street lights. Commenting on the findings, Peter Harrison from the Institution of Lighting Professionals, said there are a number of reasons we need lighting on our streets at night, so this study does not mean we should be switching all our street lights off.

“The way people use spaces is complex and multifaceted,” said Harrison. “This report looks at part of the picture and its valuable findings are just one piece of a bigger jigsaw. However, this should not be seen as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution. The report also did not mention the impact that lack of lighting had on the elderly and more vulnerable in society— their fear of crime and their reluctance to leave their homes at night.”

Steve Fotios, a lighting and visual perception researcher from the University of Sheffield was surprised by the study’s findings. Fotios, who did not work on the new study, said local decisions about how to light streets at night should be guided by evidence, and while these findings do indicate switching streets lights off may reduce vehicular crime there also may be a sweet spot of dim lighting that both reduces criminal acts and suits the needs of a local community.

“We need to be sure that lighting achieves the goals that we assume it will achieve when following lighting design guidance,” said Fotios. “The reduction in vehicle crime found by this study is surprising; further empirical research is needed to evaluate optimal light levels for residential streets after dark.”

The new study was published in the Journal of Quantitive Criminology.