Scientists have identified the oldest known Homo sapiens footprints. Found in South Africa, the tracks have been dated to over 150,000 years ago.

A wealth of fossil evidence has pinpointed humanity’s homeland as somewhere in Africa, where Homo sapiens first diverged from earlier species about 300,000 years ago. But it’s not just bones that tell this story – tools, art, food and other traces can help fill in gaps about how our ancestors lived and spread across the globe.

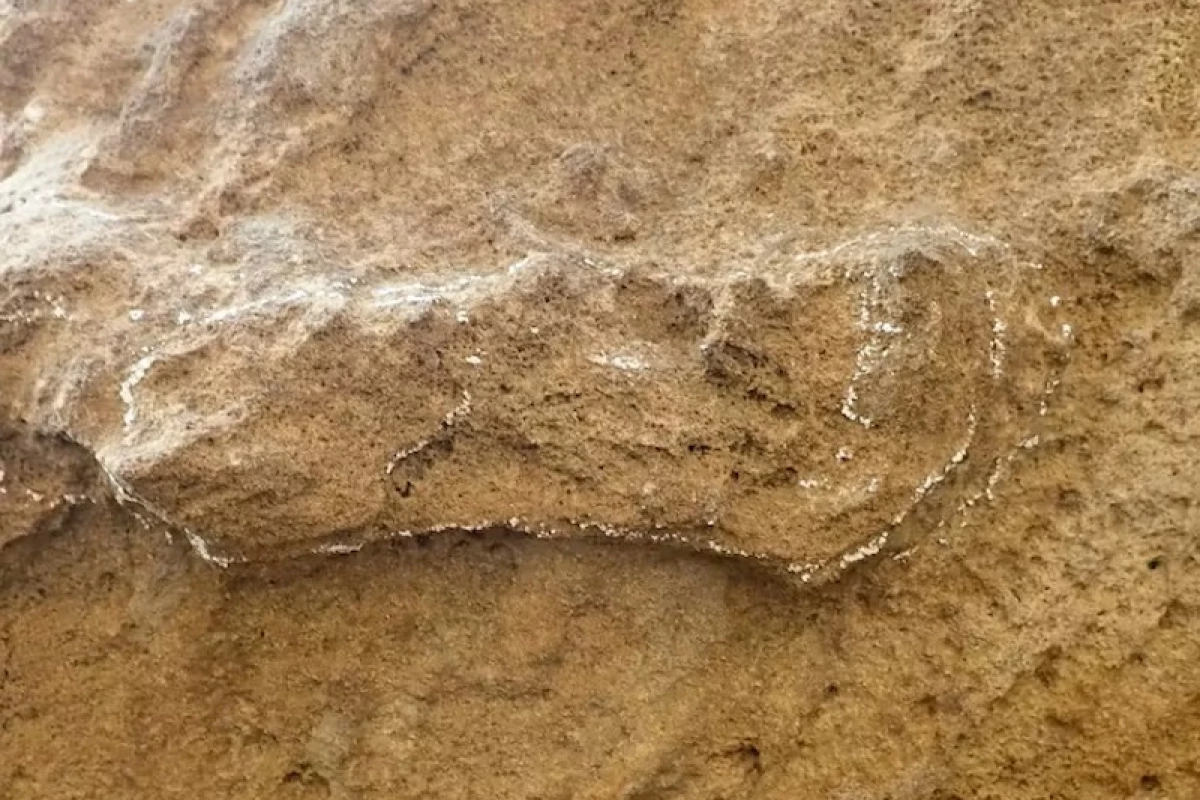

Now, an international team of scientists has identified the oldest known set of fossil footprints from a member of our species. The team calculated the dates of seven “ichnosites” (locations containing ancient human traces) along South Africa’s Cape south coast, and found that they ranged between 71,000 and 153,000 years old. The latter site comfortably claims the title for world’s oldest known Homo sapiens footprints – although there are of course older examples known from other related species.

This shows that the Cape south coast was a comfortable enough place for humans to thrive for tens of thousands of years, even while their neighbors to the north had started migrating out into other regions. Other footprint evidence shows that modern humans had reached the Arabian peninsula by about 120,000 years ago, and North America around 22,000 years ago.

The researchers on the new study managed to date the South African footprints using a method known as optically stimulated luminescence. Essentially, scientists take grains of quartz and other minerals from a sample, and expose them to ionizing radiation. The way the grains fluoresce after this exposure can reveal how long it’s been since they last saw sunlight – or in other words, how long they’ve been buried.

The tracks on the Cape south coast are particularly well-suited to being dated through optically stimulated luminescence, the team says. That’s because they were made in wet sand dunes, which are rich in quartz grains, and then quickly covered by new sand blowing over the top of them.

The team says that more ichnosites are likely still waiting to be found in the area, which could help fill in even more gaps in our understanding of our own history.

The research was published in the journal Ichnos.

Source: The Conversation