A team of astrobiologists at the University of Bremen's Center of Applied Space Technology (ZARM) has grown cyanobacterium at low pressure using only Martian materials, demonstrating future astronauts could grow their own food and other resources on the Red Planet.

When the first astronauts land on Mars, it won't be a short visit. Given the state of space propulsion technology and the rigid rules of celestial mechanics, a Mars mission means a very long wait until Earth and Mars are in the right position for the return trip. This is a major hurdle because taking along enough supplies to last on a mission that could take over two years would be prohibitively expensive.

As an alternative, mission planners at NASA and other space agencies are looking at ways of living off the land. Specifically, they want to find ways to grow food on Mars to supplement the cargo rations brought from Earth by using the nitrogen and carbon dioxide from the Martian atmosphere and the Martian soil or regolith.

For the ZARM study, a team led by Cyprien Verseux looked at Anabaena cyanobacteria, which can produce oxygen for life support systems and fix atmospheric nitrogen into sugars, amino acids, and other nutrients that can support the growing of food from microorganisms or other crops.

Unfortunately, the Martian atmosphere is extremely tenuous with a pressure that in a hundredth that of the Earth's. As a result, liquid water can't exist on the surface and there isn't enough nitrogen in a volume of air to support cyanobacteria metabolism. The answer to this would be to grow the bacteria in a pressure vessel, but these would be heavy, complicated, and would need gases imported from Earth, which defeats the purpose.

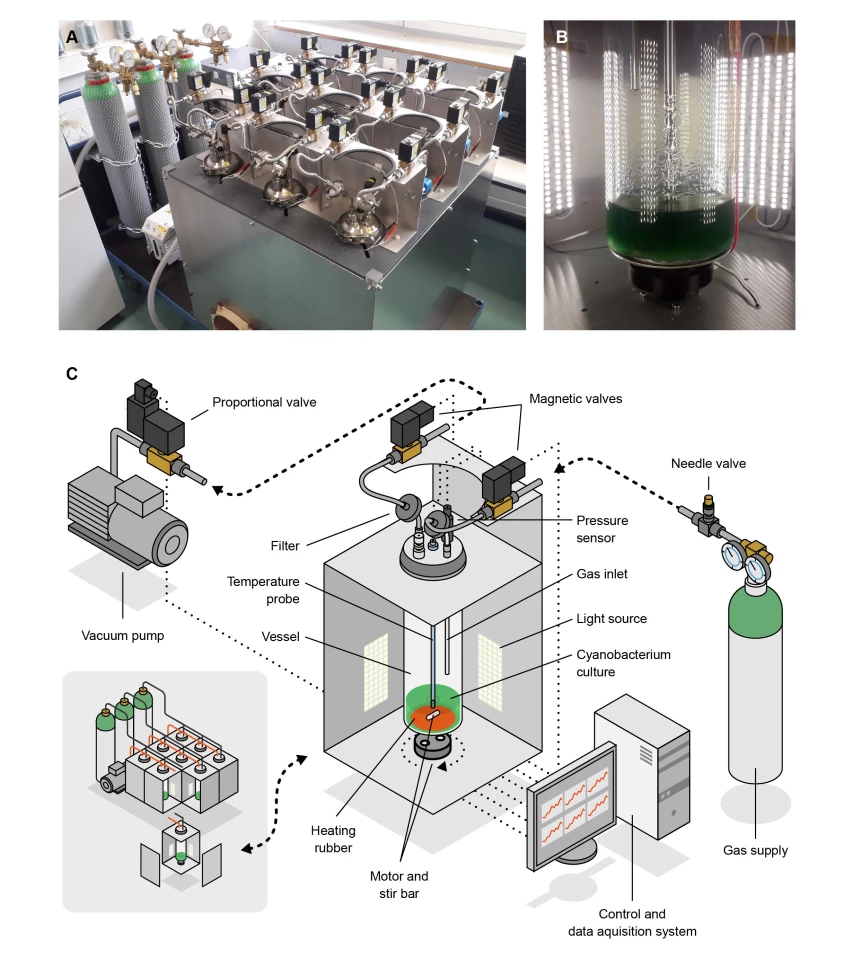

To overcome this, the team produced the Atmosphere Tester for Mars-bound Organic Systems (ATMOS) bioreactor composed of nine one-liter glass and steel vessels that are sterile, heated, pressure-controlled, and digitally monitored. Inside this, the cyanobacteria were introduced into a mix of four percent carbon dioxide and 96 percent nitrogen, along with artificial Martian regolith, which contains nutrients, including phosphorus, sulfur, and calcium.

The clever bit is that during the 10-day growth period the vessels were pressurized to 10 percent of an Earth atmosphere rather than the one percent found on Mars. For the experiment, the Mars Global Simulant artificial regolith was used as the growth medium and a standard medium was used as a control.

Not surprisingly, the bacteria grew better on the standard medium, but it also grew well on the regolith, which means that it may be possible to grow useful bacteria on Mars without having to import growth media from Earth. However, there is still work to be done.

"We want to go from this proof-of-concept to a system that can be used on Mars efficiently," says Verseuxays. "Our bioreactor, ATMOS, is not the cultivation system we would use on Mars: it is meant to test, on Earth, the conditions we would provide there. But our results will help guide the design of a Martian cultivation system. For example, the lower pressure means that we can develop a more lightweight structure that is more easily freighted, as it won’t have to withstand great differences between inside and outside."

The research was published in Frontiers in Microbiology.

Source: Frontiers