Data from China's Chang'E-5 lunar lander analyzed by an international team led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences shows that the robotic spacecraft has, for the first time, detected traces of water in the rocks and regolith on the Moon's surface.

The fifth lunar mission launched by China and its third lander mission, Chang'E-5 made history on December 17, 2020 when it's ascent stage and the mission's orbiter returned the first lunar samples to Earth since the Soviet Union's Luna 24 mission in 1976.

Though the mission was a success, the lander lacked a radio-thermonuclear unit to keep it warm through the -310 °F (-190 °C) 14-day lunar night during which its electronics froze and failed. However, the information gathered by the mission during the brief surface mission is still returning surprising dividends.

One of these involves something that is more valuable than gold when it comes to future lunar missions and the establishment of permanent human outposts: water. If a large supply of the wet stuff can be secured on the Moon, it will provide future missions with not only a source of drinking water, but also oxygen and hydrogen that can be used to produce air for breathing, rocket fuel, and the raw material for a staggering array of industrial processes.

So far, all of the water detected on the Moon has been from orbiting spacecraft using remote sensing to uncover water ice hiding in the permanent shadows of the lunar south polar region, but the new study that included scientists from the National Space Science Center of CAS, the University of Hawai′i at Mānoa, the Shanghai Institute of Technical Physics of CAS, and Nanjing University has found the presence of water in the form of H₂O or OH hydroxyl molecules in the Northern Oceanus Procellarum basin much closer to the lunar equator.

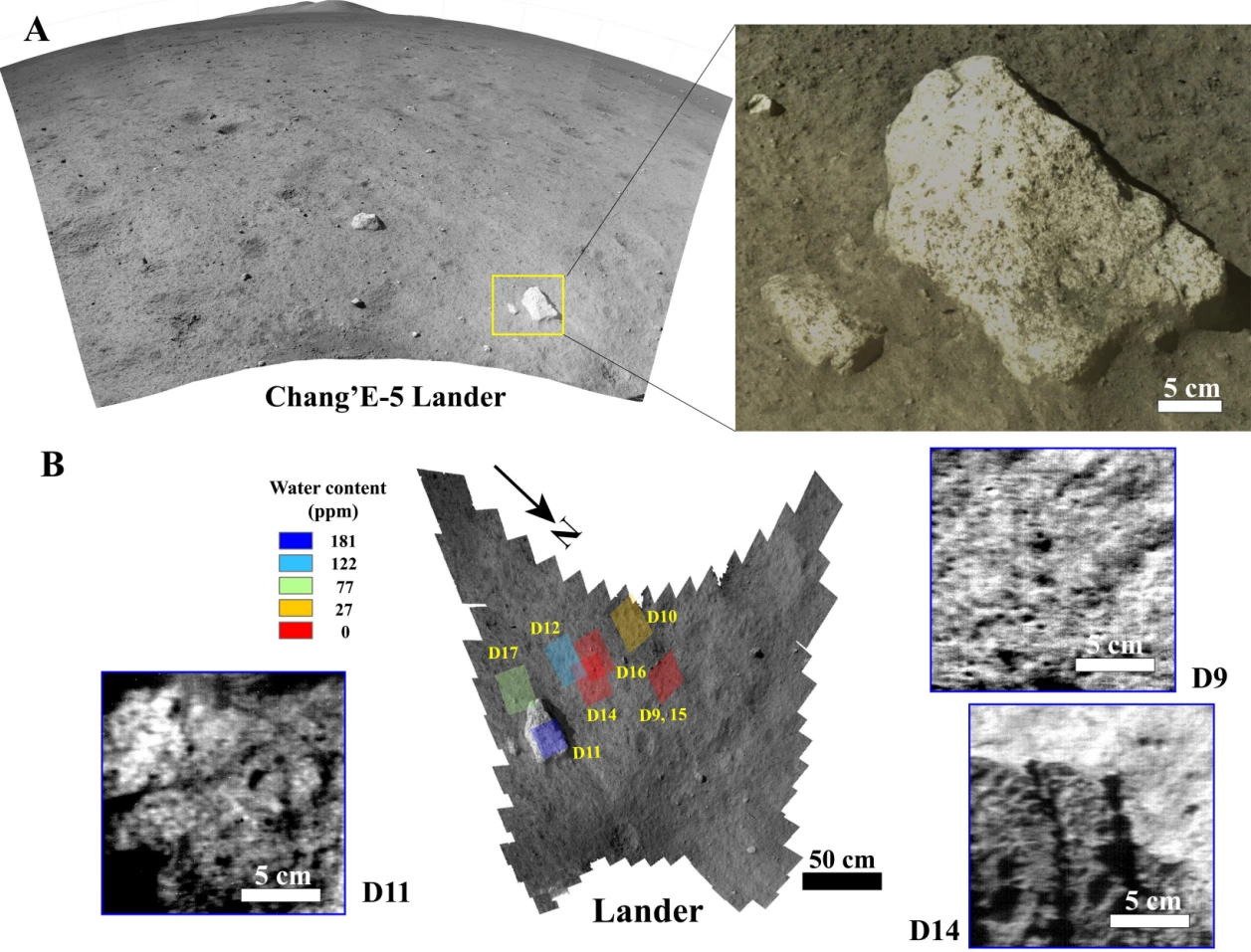

The area where Chang'E-5 touched down is a lava plain that is made of some of the youngest mare basalts on the Moon. Using the lunar mineralogical spectrometer (LMS) onboard the lander, mission control carried out spectral analysis of light reflecting off the regolith on the surface and a rock in the vicinity of the lander.

According to the team, the heat coming off the lunar surface during the daytime would have overwhelmed the spectral records, but using a thermal correction model to correct the LMS spectra allowed the scientists to see the spectrographic signature of water, showing that the regolith holds less than 120 ppm of water, which is similar to the amount found in the samples returned to Earth by the mission. This isn't surprising, and what little water there is is probably the result of molecules brought to the Moon by the solar winds.

But on examining a light and vesicular rock, the instrument showed that it contained about 180 ppm of water. That might not seem like much, but because the rock may have come from an older layer of basalt beneath the lunar surface that was thrown out by a meteor impact, it may mean that there was an outgassing of water from the interior of the Moon sometime in the past that was trapped in the basalt. This means that there may be sources of water away from the poles, locked in rocks that could one day be tapped.

The research was published in Science Advances.

Source: Chinese Academy of Science