Rockets are expensive, complex, bad for the environment and prone to occasionally exploding – so alternative launch technologies are popping up to reduce their use. We wrote about SpinLaunch's remarkable kinetic launch system earlier this week, which spins a rocket up to incredible speeds on the end of a long, carbon-fiber arm in a vacuum chamber, then releases it skyward at speeds up to and over Mach 6.

Then another company dropped us a line, to show us a far simpler approach it says can get launch vehicles and ruggedized electronic cargo off the ground at nearly three times that velocity, with a quicker turnaround time. This time, it's basically a huge gas cannon.

Green Launch COO and Chief Science officer Dr. John W. Hunter directed the Super High Altitude Research Project (SHARP) program at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory some 30 years ago, and in the process led the development of the world's largest and most powerful "hydrogen impulse launcher."

This is effectively a long tube, filled with hydrogen, with helium and oxygen mixed in, and a projectile in front of it. When this gas cannon is fired, the gases expand extremely rapidly, and the projectile gets an enormous kick in the backside. The SHARP program built and tested a 400-foot (122-m) impulse launcher in 1992, breaking all railgun-style electric launcher records for energy and velocity, and launching payloads (including hypersonic scramjet test engines) with muzzle velocities up to Mach 9.

Here it is in slow motion, a 4-megajoule horizontal test shot filmed at 12,500 frames per second:

Or, if you prefer, at actual speed, which looks a teensy bit more violent:

This approach, says Green Launch Business Development Director Eric Robinson, scales up far better than a spinning accelerator like the SpinLaunch system.

"The record for a projectile launched with hydrogen propellant is 11.2 km/sec (Mach 32.7)," he tells us in an email. "We plan to limit our launch velocity to 6 km/sec (Mach 17.5) to extend reusability and prevent wear on the barrel."

As with the SpinLaunch system, the Green Launch projectile would need to fire a small, second-stage rocket to give it a final burst of acceleration and steer it into the correct orbit. But since the hydrogen cannon will launch it so much faster, this rocket can be considerably smaller and lighter.

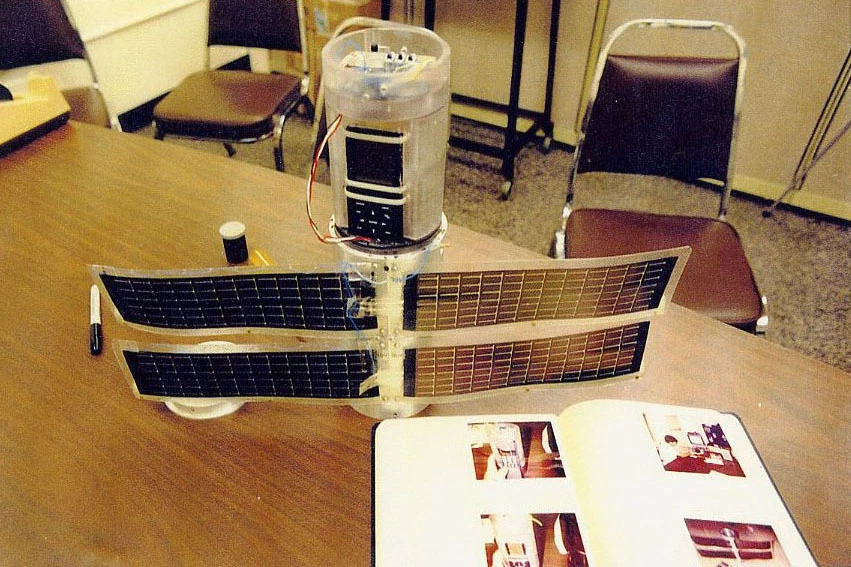

Small and light will definitely be the order of the day here, because all systems involved in a hydrogen impulse launch ... well, they're going to be shot out of a cannon. Green Launch estimates the acceleration forces involved will peak at around 30,000 G, and it's got a simple enough test for whether a piece of electronics can withstand that sort of shunt: sticking the component to a golf ball with epoxy and whacking it with a three wood.

That produces a similar level of acceleration, says the company, and it poses no problem even to many off-the-shelf electronics components. Small, ruggedized satellites should be no problem.

Green Launch says the cost will be minimal – maybe a tenth of what it costs to put things on a rocket. Plus, dropping the first-stage rocket eliminates a whole lot of burned fuel and associated emissions, since the hydrogen burns clean and emits only water and a very big bang. It'll also allow constellation owners the ability to spread risk over multiple launches rather than lose 200 satellites in one rocket explosion.

The hydrogen cannon can be fired every 60-90 minutes, sending its hypersonic projectile skyward where it'll "penetrate the atmosphere within a minute and shed its aeroshell." Low earth orbits between 300-1,000 km (186-621 miles) can be achieved in under two hours, and some much quicker. "Your satellites and supplies can be in orbit in 10 minutes," says Robinson.

The company has built a 54-ft (16.5-m) proof of concept launch tube, and just before Christmas last year the team aimed it vertically upwards at Arizona's Yuna Proving Grounds for its first vertical test shot, achieving a muzzle velocity "exceeding Mach 3," and firing the projectile well into the stratosphere. Later this year, the team aims to ramp up the velocity enough to get a projectile to cross the Karman Line, 100 km (62 miles) above the Earth, and enter into what's referred to as the beginning of space.

"Our current collaborators and customers include UCSD and Harvard on an NSF sponsored project," says Robinson. "We will be sampling the mesosphere between 30 km and 100 km in order to determine the isotopic gas content. This has great bearing on the Earth's energy budget and provides physical data for climate scientists around the world. Green Launch is uniquely able to take biopsies of the Earth's atmosphere at altitudes too high for balloons and too low for satellites. Sounding rockets are much more expensive as well as very polluting."

"Based upon our recent success at the Yuma Proving Ground," he continues, "we are entering a new development round for our suborbital then first orbital system."

Check out the vertical test shot in the video below.

Source: Green Launch