The James Webb Space Telescope may have been touted as a successor to Hubble, but the old-timer still has some life left in it yet. These two iconic instruments have now teamed up to take a star-studded deep-field image of the colorful “Christmas Tree galaxy cluster.”

The Hubble Space Telescope has been a constant source of stunning images since its launch in 1990, but it’s not headed for the scrapheap just because a flashy newcomer has taken to the skies. Hubble observes the universe primarily in visible wavelengths – those that the human eye can see. Webb, meanwhile, focuses on infrared light, which is better for seeing objects farther away in space and time.

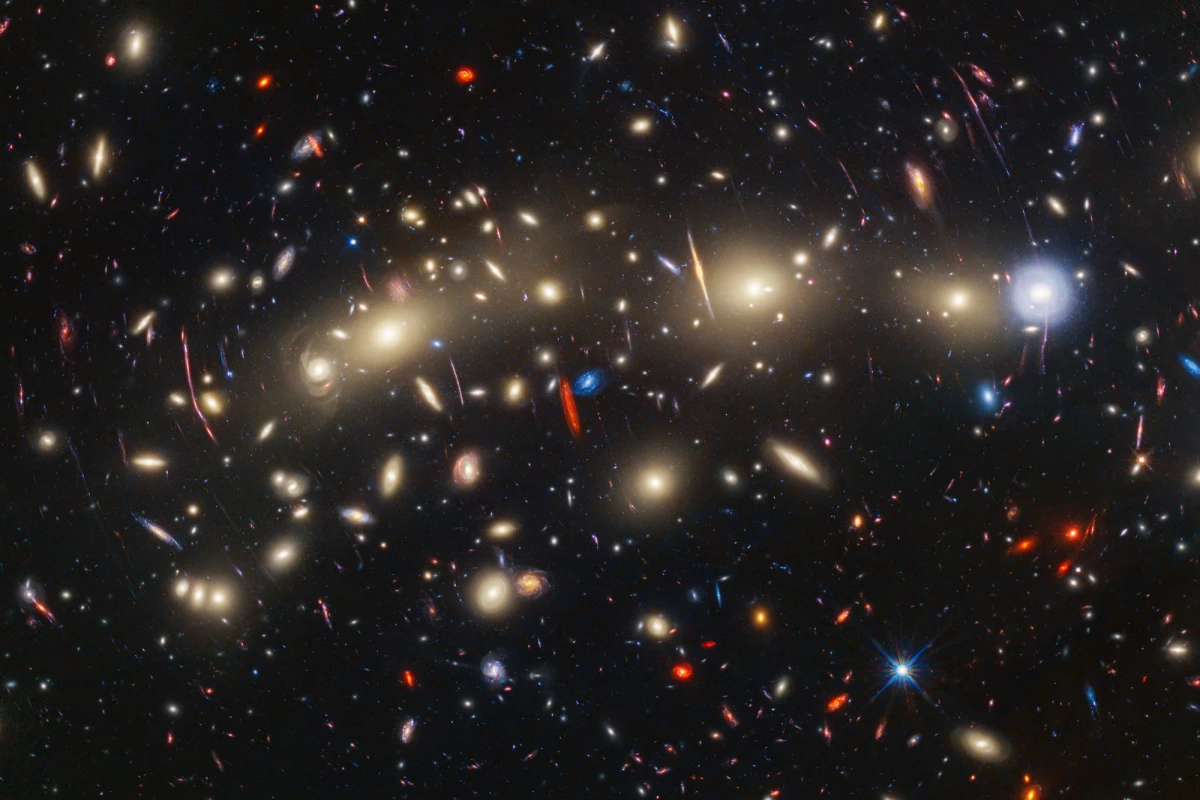

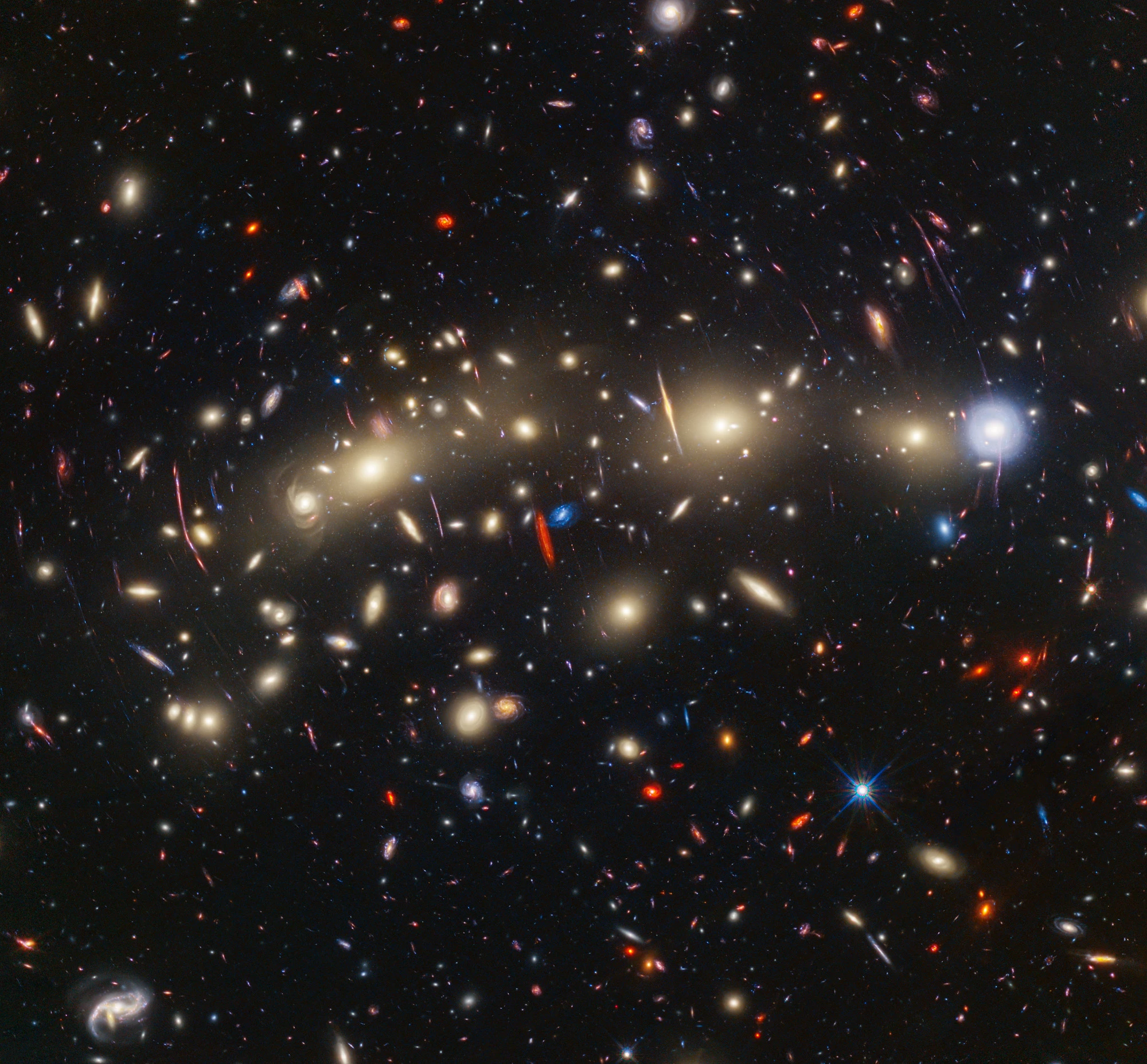

Now, astronomers have combined these two unique views of the universe to image one region of space in more detail. The subject is a galaxy cluster known as MACS0416, located about 4.3 billion light-years from Earth. In fact, two galaxy clusters are currently in the process of merging, so that they’ll eventually form one giant cluster. Some of the objects in the image are actually much farther away, but have had their light magnified or distorted due to a phenomenon called gravitational lensing.

The Hubble images were originally taken back in 2014, requiring some 122 hours of exposure time. The Webb images were taken earlier this year over the course of about 22 hours, allowing an entirely new set of galaxies to come into focus.

In the resulting composite image, the different colors of light indicate the galaxy’s distance and which telescope imaged them. The blue galaxies are those with the shortest wavelengths, most visible to Hubble and are generally those that are closer to us here on Earth. Greens and yellows sit in the middle, while red galaxies are the work of Webb – they’re generally much farther away or shrouded in dust, remaining largely invisible to Hubble.

“We are building on Hubble’s legacy by pushing to greater distances and fainter objects,” said Rogier Windhorst, an author of the Webb study. “The whole picture doesn’t become clear until you combine Webb data with Hubble data.”

The Webb images weren’t purely taken for aesthetic purposes though. The team was searching for “transients” – objects that vary in brightness over time – so they conducted multiple observation sessions with a few weeks in between, to see what changed. Within this field of view, they spotted 14 transients, with 12 concentrated in three galaxies that are highly magnified by gravitational lensing. That suggests they were individual stars or star systems that briefly passed into a specific alignment that magnified their brightness dramatically. The other two were likely to be supernovae, the team says.

“We’re calling MACS0416 the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster, both because it’s so colorful and because of these flickering lights we find within it,” said Haojing Yan, lead author of one of the studies. “We can see transients everywhere.”

One study was published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, while the other has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Source: NASA