Most meteorites that fall to Earth belong to one of two broad groups – there are rocky ones, and there are metallic ones that were once molten iron. But one puzzling group of meteorites appears to belong to both camps at once, and now scientists have determined that the parent body had a rocky shell and a liquid metal core, which likely generated a strong magnetic field.

The most common type of meteorite found is the stony variety, which remain “unmelted” through their life cycle. Iron meteorites, on the other hand, bear the hallmarks of having been melted at some point, cooling and condensing into lumps of solid metal long before they hurtled to Earth.

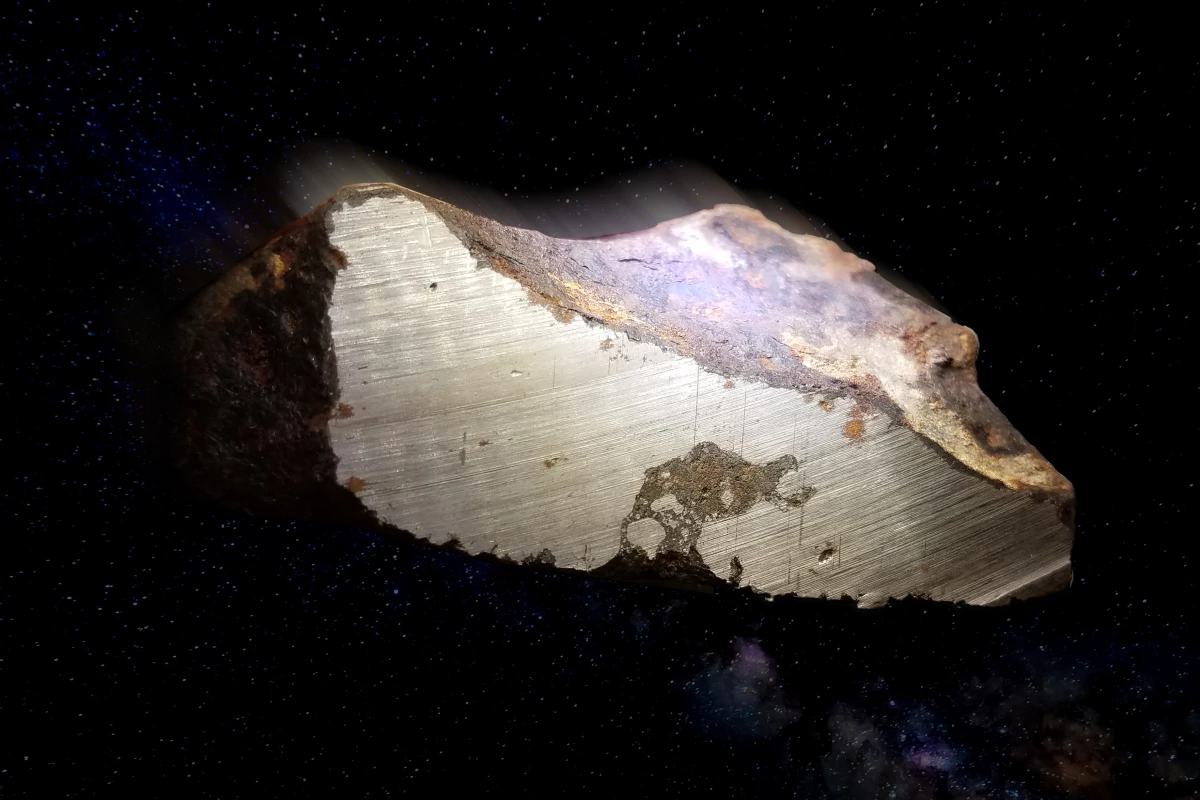

And then there are the IIE meteorites. These weird middle-ground objects appear to be both types at once, made up of once-melted metal with rocky inclusions. More than 20 of these have been discovered since the 1960s, and they’ve been found to have come from a parent body that had a liquid metal core wrapped in a rocky outer layer.

For the new study, researchers at MIT and the University of Chicago wondered whether this structure would have created a magnetic field. After all, Earth’s magnetic field is produced in its churning liquid metal core, and extends far above its rocky exterior.

To investigate, the team set out to find evidence locked in minerals in these IIE meteorites. The same way the needle of a compass always points north here on Earth, electrons in mineral grains in these meteorites will tend to align in the same direction in the presence of a magnetic field.

So the researchers used the Advanced Light Source (ALS) laser to check. This powerful laser beam generates X-rays that can determine the magnetic direction of minerals, right down to the nanoscale. And sure enough, the electrons inside a number of these grains did align in the same direction.

The team calculated that the parent object’s magnetic field must have been around the strength of Earth’s, and generated by a liquid metallic core that measured a few dozen kilometers wide.

Simulations suggest that an object with such a complex structure would have taken millions of years to form in the early days of the solar system. And it would have taken many collisions with other objects to dislodge the minerals in the liquid core. First they would have ended up in the rocky outer shell, where they cooled and recorded the imprint of the magnetic field. Then, further collisions would have shaken them loose, where they would float around and eventually fall to Earth.

The team says that it’s hard to tell if rocky objects with liquid metal cores are common or rare. But future studies could look to the asteroid belt to find out.

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: MIT