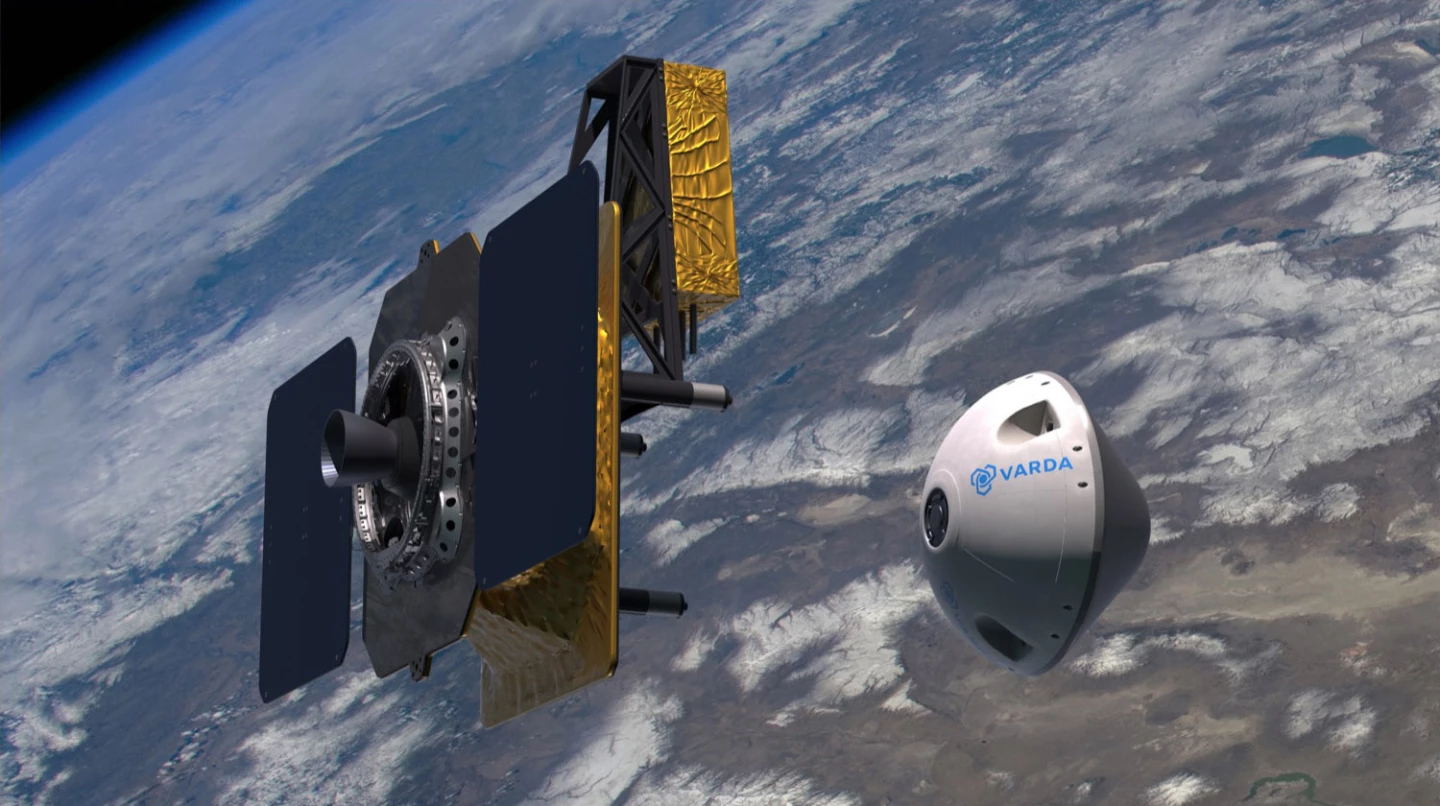

California startup Varda has celebrated the deployment of its first satellite, a test run of a fascinating space-based pharmaceuticals factory that moonlights as a hypersonic test rig during its Mach 25 re-entry to keep costs down.

Why manufacture in space? Well, when you're operating in zero gravity – or at least, in the microgravity environment of orbit – you're altering a very significant physical variable that's pretty much a constant for any Earth-based lab.

With gravity out of the equation, things like convection currents don't exist, because there's no "up" for heat to rise towards. And particles in liquid don't form clumps and rise to the surface or sink to the bottom like they do on Earth.

"The resulting tunable particle size distributions, more ordered crystals, and new forms," reads a Varda pamphlet, "can lead to improved bioavailability, extended shelf-life, new intellectual property, and new routes of administration."

These and other factors have proven extremely helpful for one particular area of R&D: protein crystal growth, which represents "by far the largest single category of experiments" undertaken on the ISS, according to NASA.

This is a particularly attractive proposition for drug developers, who can use zero-gravity environments to crystallize biological proteins in order to analyze their structure and design medications to perfectly bind to them.

But they can also use a microgravity lab to manufacture their drugs in crystalline forms with extraordinary precision. We're not talking about whole tablets here, complete with binding agents and other cheap additives. But the active ingredients for these drugs can command an absolutely insane amount of money per kilogram.

Not Boring, working alongside Varda, has dug up some examples, the most outlandish of which is leukaemia immunotherapy drug Blincyto, at a cool US$114.3 billion per kilogram. Or the mRNA at the heart of Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine; two gallons of that would make every dose that Pfizer has made to date – and those doses have generated more than $75 billion for Pfizer, or, as Not Boring puts it, a stack of hundred dollar bills that'd reach up 82% of the way to space.

So a space-based lab represents a unique production environment for both R&D and the manufacture of incredibly high-value substances – one that can be kept surgically clean and that can do things on the micro scale that simply can't be achieved on the ground.

And on the other side of the coin, costs per kilogram for space launches are famously crashing right now thanks to private space companies like SpaceX with their reusable rockets. Once Starship is up and running, those costs will plummet even further.

Doing things in space is thus rapidly becoming so cheap and accessible that it no longer has to be thought of as a "sometimes treat" for companies producing things like drugs, superconductors or superalloys.

Varda is simply the first company to get a space-based manufacturing satellite into orbit. There will be plenty of others coming.

W-Series 1 Satellite has DEPLOYED!! pic.twitter.com/di13aAR1Je

— Varda Space Industries (@VardaSpace) June 12, 2023

Varda's first "space factory" launched yesterday aboard a Falcon 9, and it's now in orbit. Over the next week, it'll run systems tests, and then, assuming all goes to plan, it'll start commercially relevant tests on an old HIV/AIDS drug called Ritonavir, heating it up and cooling it down to examine the differences in its crystalline structure when the crystals are grown in space.

The factory, about the size of a yoga ball, will orbit around for a little over a month at an altitude over 1,000 km (621 miles), after which it'll fire off a retro-booster angled to slow it down enough that it'll fall back down to Earth.

As it drops through the vacuum of space toward its eventual landing spot at a US Air Force range in Utah, it'll accelerate to hypersonic speeds over Mach 25 (19,200 mph/31,000 km/h). The atmosphere will slow it down and heat it up as the air begins to get thicker, but it'll stay in the hypersonic range above Mach 5 (3,800 mph/6,200 km/h) until it's about 40 km (25 miles) from the surface.

And here's where Varda has applied some clever commercial thinking; since the thing's going to be doing hypersonic speeds anyway, Varda has packed up a "re-entry as a service" proposition that'll allow various US government hypersonic R&D programs to perform critical testing in a considerably more mission-relevant environment than the world's most advanced Mach 15 air tunnel facilities.

Varda has been awarded a $60m Air Force STRATFI contract to advance our nation’s hypersonic capabilities

— Varda Space Industries (@VardaSpace) March 15, 2023

The Air Force will utilize our re-entry vehicle as a hypersonic test-bed while flying back to Earth after microgravity production pic.twitter.com/R6ZkSzxsFj

It's a terrific little two-birds-one-stone proposition, and a huge help in terms of generating revenue. In the long run, this kind of dual-purpose operation will make things cheaper for all parties involved.

By the time the spacecraft falls to the cruising altitude of a commercial airliner, it will have slowed to around 168 mph (270 km/h), at which point it can start deploying parachutes to bring it down for a gentle landing. The harsh conditions of re-entry won't affect the crystalline drugs on board, so it'll effectively be like a little delivery box from heaven.

If all goes to plan, Varda has a second mission scheduled for later this year – and this one will get the party started with actual commercial and government clients, in a manufacturing and testing arrangement the company believes will be commonplace within a couple of years. It'll also mark an incredibly quick journey from startup to first revenue in a space-based company; Varda was founded less than two and a half years ago.

The company has plans for reusable space factory modules, and it's also already considering the idea of running a manufacturing station that stays permanently in orbit, ferrying materials, equipment and maintenance gear up to dock with it as necessary. These measures are off in the medium-term future, but the age of the space factory has now officially begun.

Source: Varda via Not Boring