Our history of the world's fastest production car is produced in three parts: pre-WWI, WWI to WWII and the already-published segment from WWII until now. This is article covers the earliest period from the first cars through to WW1. The nature of the data available means we've had to rely on disparate data points and some ballpark figures in tracing the early development of the fastest road cars, making it less clinical than our look at the cars of the modern era, but no less fascinating.

The modern car evolved from initial attempts to motorize a horse-drawn carriage in just two decades, from 1894 to 1914. In many ways, the rise in speeds from 1894 to 1914 charts that wave of innovation: from one cylinder to 12 cylinders, from two- to four-wheel brakes, from side-valve to DOHC 4-valve hemispherical combustion chambers, from open to streamlined, from solid axles to pneumatic suspension and incredibly, from 12 mph to 120 mph.

In one generation, the automobile was embraced by civilization as a symbol of personal freedom. The initial circumstance was ideal for the success of the automobile, as a ready-made market existed comprised of the millions who had experienced personal transport's first "killer app" – the bicycle.

Viewed in this narrow time-frame, the automobile's top speeds increased on average more than 5 mph per year for 20 years from 1894 to 1914. This was Moore's Law v 0.9.

When road registration laws were not black and white

Defining a road car during this period of time is problematic, as race cars and record cars were almost always based on road cars. It was a different time, and cannot be seen clearly with a mentality framed by 21st century mass production and road registration rules. Each jurisdiction meant that different road registration rules and applications of those rules existed and as you'll see in the research below, purpose built racetracks didn't exist, so all competition was staged on public roads throughout this period.

Personal transportation pre-history

In 1900, a mass market for personal transportation had already existed for thousands of years – the horse drawn carriage. The largest producer of horse-drawn vehicles in the USA was Durant-Dort which was selling over 150,000 carriages a year and already had sophisticated manufacturing operations and a sales channel to America's wealthy. There was life before the motor car, just at a more leisurely pace.

Trains owned the luxury travel market

Trains owned the market for luxury long-distance land travel at this time as the only alternative was the horse-drawn carriage over rough roads, with river boats and steam ships offering painless long-distance travel to only the most affluent.

Steam trains were still considerably faster than any other land vehicle. In 1891, at a time when the motor car was struggling to become a commercial reality, the Empire State Express covered the 436 miles from New York to Buffalo in 7 hours 6 minutes, averaging 61.4 mph (98.8 km/h), with a top speed of 82 mph (132 km/h).

In 1893 the same company's latest 4-4-0 steam locomotive (No. 999 above) was capable of 100 mph. So by the time of the first record attempts were made by automobiles, they were a long way behind the steam train.

The dawning of the automotive age

Trains might have owned the market for luxury long-distance land travel, but automotive pioneers could see that would change once the engine, roads, tires and cars achieved their full potential.

An automobile would ultimately offer greater possibilities than the steam train, most notably being able to transport you quickly and safely from A to B, instead of the train's station A to station B.

The world's road infrastructure was in its infancy 100 years ago. The first automobile crossing of America was not achieved until 26 July 1903. The 4,500-mile journey had taken 63 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes. The same New-York Los Angeles road record now stands at 28 hours and 50 minutes.

Before the production line, cars were built one by one

The vast majority of the world's cars prior to 1907 were built in Europe, with America overtaking France as the leading car manufacturer in the world in 1904 by volume and in 1905 by value. By 1907, America's 250 car manufacturers were producing more cars (44,000 per year) than France, Britain and Germany combined, and America's more equitable income distribution and far higher average wages put the dream of personal transportation within reach of the common man.

Ultimately, although America would start behind the European countries in its quest for mass personal transport, it would put the freedom machine in the hands of the people a full generation ahead of Europe.

Production capabilities were growing quickly in 1907 as America embraced the new low-priced four-cylinder Ford Model N and Buick Model 10 "Nifty". Ford was producing 100 Model N cars a day in one factory and the 6000 cars it made in 1908 were behind only Buick's 9000 as they fought to be the largest car manufacturer in the world.

From five vehicles for every 1000 Americans in 1910, there were 86 vehicles for every 1000 people by 1920, and by the end of WW2, Europe lay in ruins while America's homeland was untouched by war and there were 220 cars for every 1000 people. In just a few decades, one in five Americans had purchased a car. Next to a home, it was the most expensive discretionary purchase most people ever made and car ownership would eventually reach eight in 10 Americans.

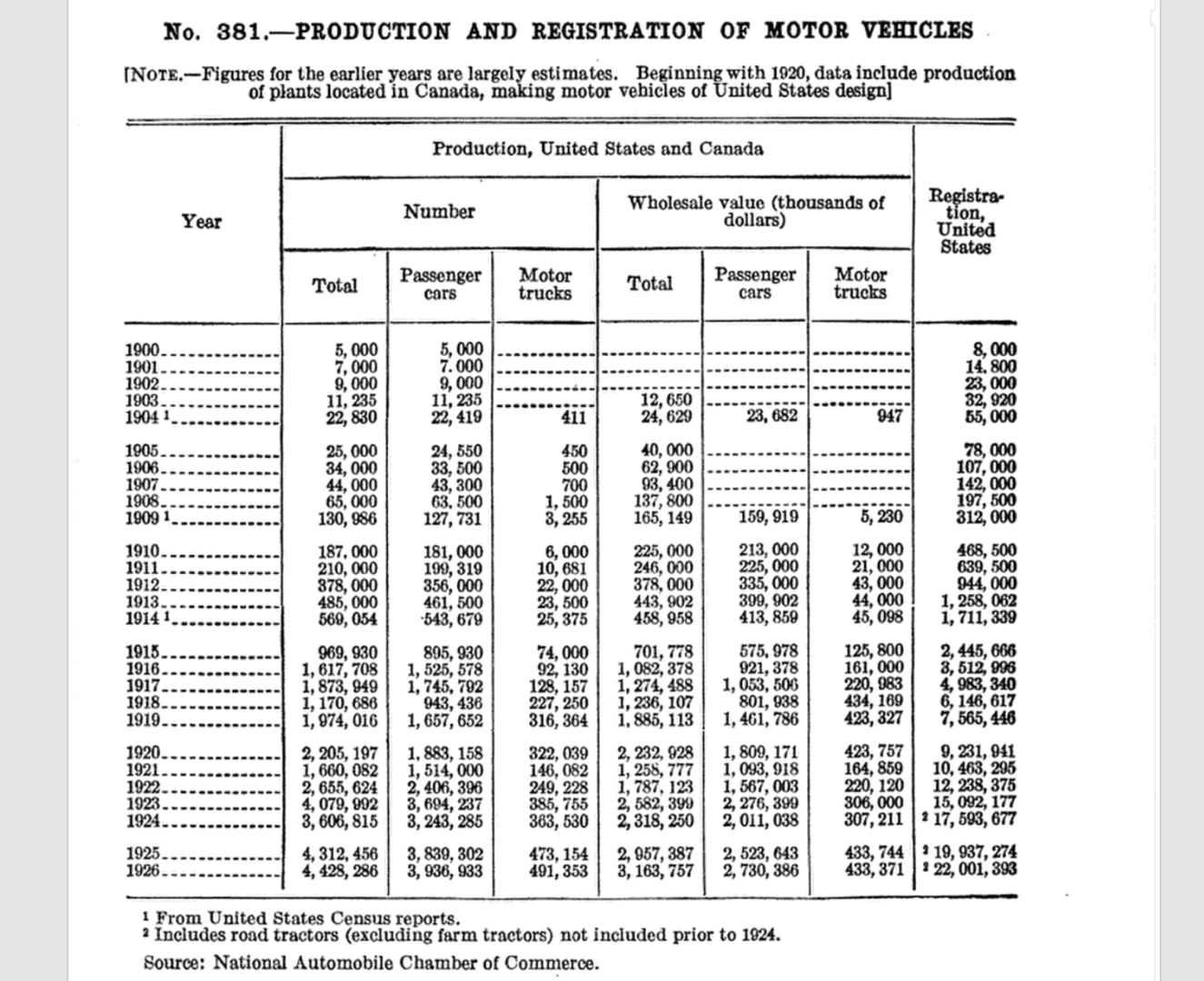

The above excerpt from this 1926 Department of Commerce Statistical Abstract of the United States clearly shows the growth of both the American automotive industry and the size of the US carpark – 8,000 cars in 1900, 400,000 in 1910, 9,000,000 in 1920 and 22,000,000 in 1926. You'll see the wholesale value of the passenger vehicles is also listed in the above table. Do the math and you'll find that the average wholesale cost of a car in 1909 was $1252. By 1916, the average wholesale price was $604.

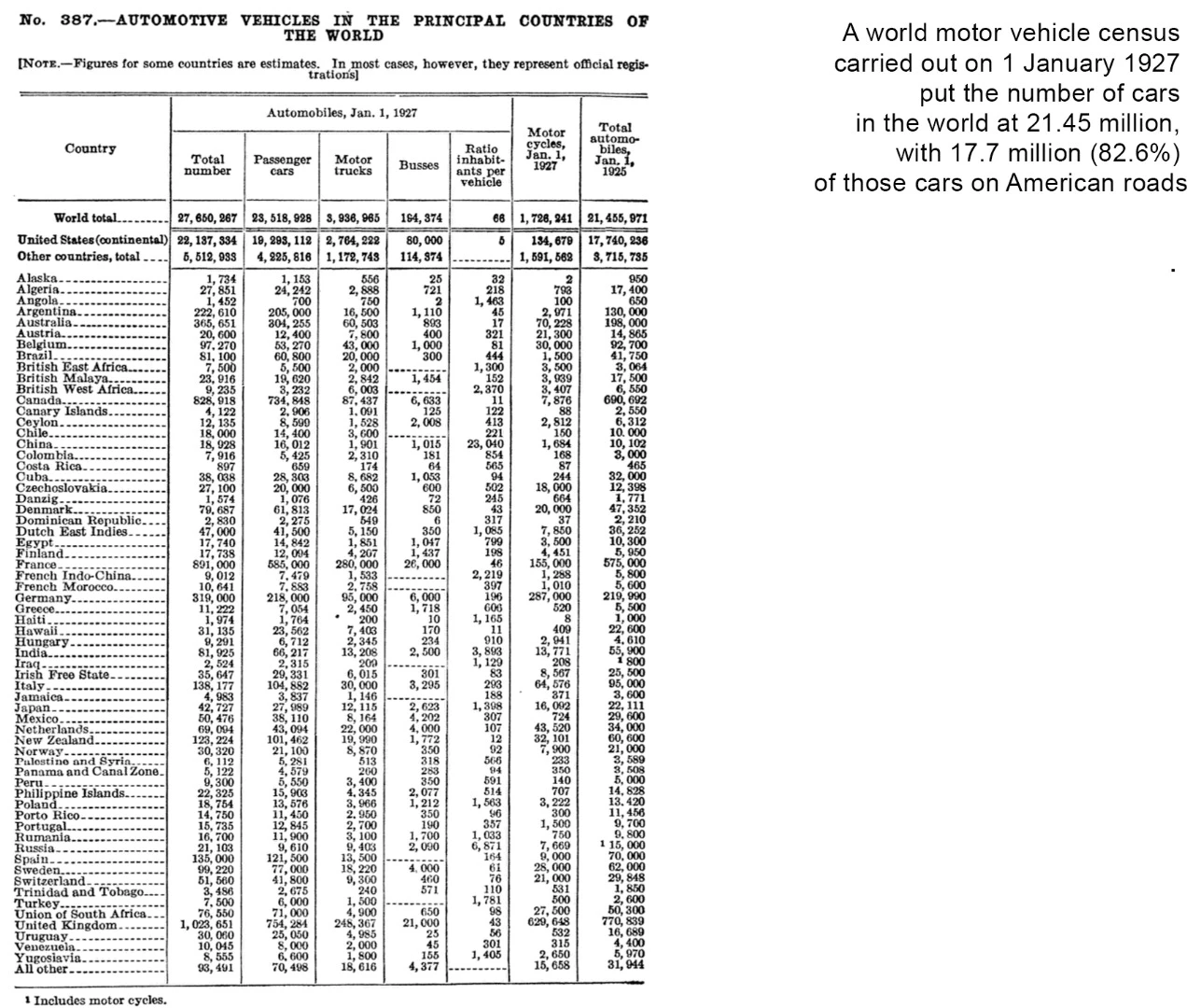

Two world wars based in Europe stimulated global technological development and the American economy, while twice near destroying all European economies, including the only other countries producing cars: England, France, Germany and Italy. By 1926, America had achieved global automotive domination, producing and consuming more cars each year than all other countries combined.

It did so by catering to the American public's need for transportation in a big country, and the compelling proposition of being able to travel vast distances in short times. Journeys that had taken days now took hours. Previously insurmountable distances now took days.

On October 7, 1913, Henry Ford's production line was switched on. Its effects on the by-then booming automotive industry were profound. The automotive industry might well be measured by the terms "Before Production-Line" and "After-Production Line."

Henry Ford's Production Line

In a world defined by economic efficiency, the coming of the production line in 1913 had a profound effect.

Before the production line, a Model T could be produced using 12.5 hours of labour. On a production line, a Model T could be produced using 93 minutes of manpower, reducing the cost of labour by 87.6 percent.

In 1910, a Model T Ford Runabout cost $900. In 1916, the same car sold for $350. By the middle 1920s, the price was $260.

Ford's price advantage meant its top selling vehicle could be offered at such a price that it drove adoption by the masses, enabling affordable personal transportation to the common man for the second time, though in a far faster and more comfortable form than the bicycle or the horse drawn carriage. Fifteen million Model T Fords would be sold in the next 20 years.

This revolutionary production technique meant that Ford grew incredibly quickly. At one stage it had produced more than half the cars in the world. Moves such as doubling the pay of his workers helped Henry Ford find a special place in modern folklore as a benevolent industrialist.

What's more, this quantum leap in technology drove America to automotive dominance globally with mass automobile production quickly reshaping not just the automotive industry but the finance, insurance, oil, tire, dealership networks, spare part supply chains and other industries around it.

The coming of the automobile industry effectively supercharged the American economy.

The Industrial Revolution (1760 – 1840) spawned new materials and manufacturing processes and efficiencies in many industries with the development of machine tools that provided the basic prerequisites for the first assembly lines. The concept of interchangeable parts is taken for granted these days, but was less than a century old when the Ford's production line began. We truly have come a long way in a short time.

Technological capability increased dramatically from 1894 onwards as a new global industry emerged and production numbers rose from thousands in those last few years of the 1890s to millions as the "century of the automobile" unfolded, bringing high speed personal transport to the masses.

The world's fastest cars from 1894 to 1914

Many very fast road cars were built from 1910 onwards, but not necessarily in large quantities, and whereas the 1945-2016 section of this history of the world's fastest cars had references to specific speeds, this part will rely more on ballpark figures and disparate data points including average speeds and distance records to trace the early development of the fastest road cars.

It's the only data available, and top speed was more theoretical then than it is now in a land where 99 percent of the roads were unpaved. Durability was the most important variable in this harsh climate, and the fastest cars of yesteryear had to have "good bones" to cope with the inevitable potholes along the way.

To put the rise of the motor car in perspective, we've also made occasional reference to other vehicles such as trains, planes and motorcycles that held speed records during the era.

Benz & Cie Velo | 12 mph (19 km/h)

Benz announced the first series production automobile at the Chicago World Expo on May 1, 1893 | Availability begins in 1894

The Benz & Cie Velo is generally regarded as the world's first production automobile, though there were many cars produced prior in modest quantities. The top speed was just 12 mph (19 km/h) so it wasn't the fastest for long, as the late 1890s was a period of great automotive innovation with ever increasing speeds in all three genres of drive train –electric, petroleum and steam power.

Unfortunately, all these cars had very low production runs, and it's difficult to say which cars were really the fastest because though electric vehicles were probably the quickest over a short distance, range was a major issue and prevented them from showing up in the longer speed trials. Steam cars offered greater power but were fraught with reliability issues on top of the inconvenience that restricted general adoption.

De Dion Bouton (Steam) | 12 mph (19 km/h)

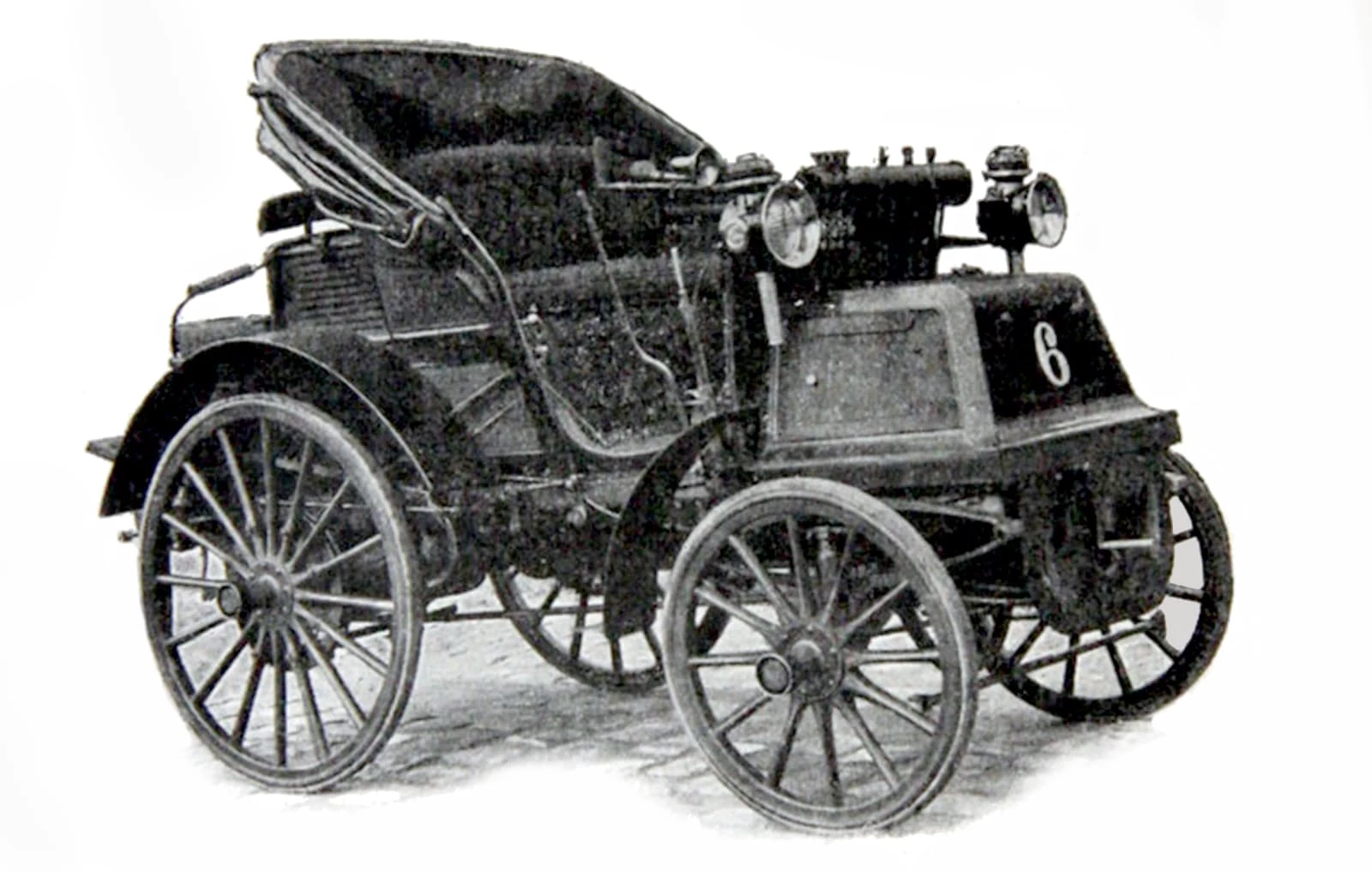

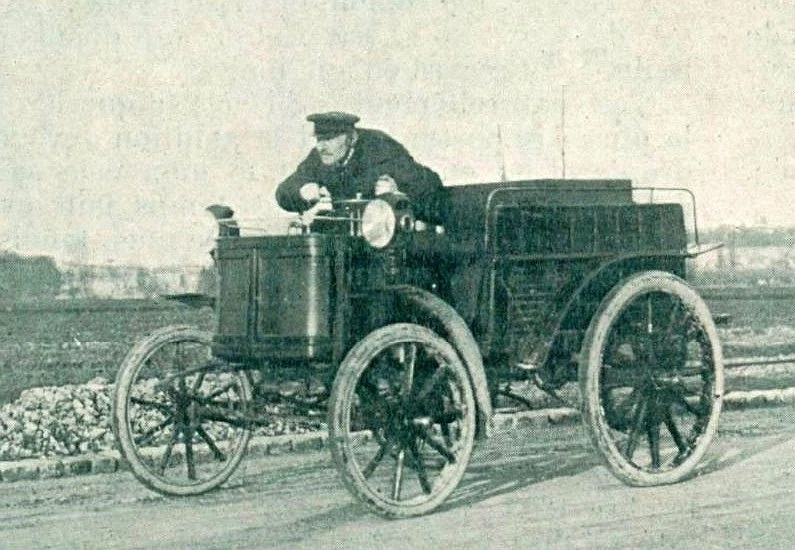

July 22, 1894 | Average speed of first finisher in the Paris-Rouen Trial

The first motorsport event in history was the 78 mile (126 km) Paris to Rouen on July 22, 1894, and the first car across the finishing line was a De Dion Bouton steam car pulling a trailer (above). Driven by Count De Dion himself, it was disqualified because it needed a stoker (someone to tend the boiler). De Dion's time for the distance was 6 hours 48 minutes giving him an average speed of 19 km/h (12 mph), indicating it had the potential to travel at much higher speeds but was no doubt limited by the solid axles of the trailer and the quality of roads. 120 years ago, the steam-powered De Dion Bouton was the equivalent of the Bugatti Veyron Super Sport.

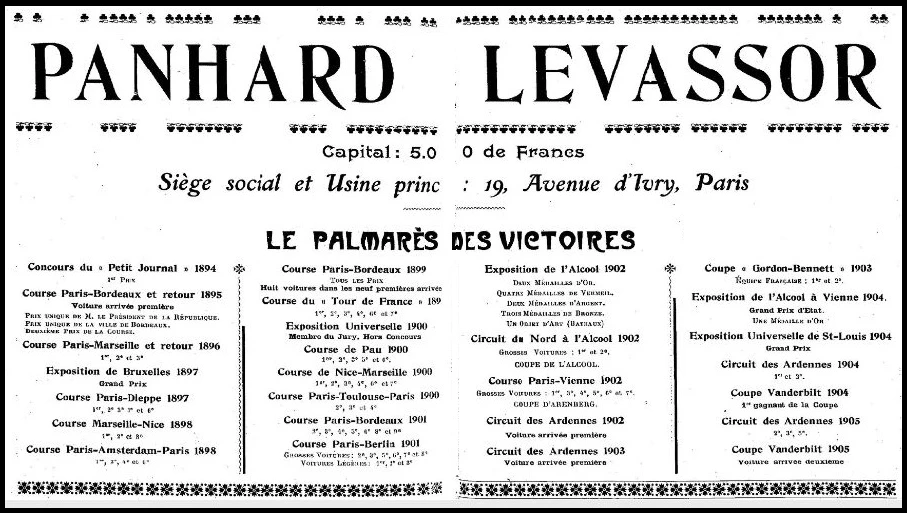

Panhard & Levassor | 15.25 mph (24.54 km/h)

July 11, 1895 | Average speed first finisher Paris-Bordeaux Race

The following year a Panhard & Levassor car driven by Émile Levassor finished first in what is generally regarded as the first true motor race, the 1,178 km Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race. Unfortunately, the race was for four seater cars and the Panhard only had two seats so it was disqualified. Levassor's time does however give us an indication of the speed potential of the fastest road car of the day, and his total time of 48 hours and 48 minutes gives an average of 24.5 km/h including several lengthy stops for meals. It's not recorded whether he slept during the ordeal.

The specimen pictured above from 1895 is an example of the type of car which Panhard & Levassor produced in those early races, all of them based on a "Système Daimler" engine license, but in a new configuration not seen previously. The company's "Système Panhard" of 1891 was the first iteration of the now familiar front-engine and rear-wheel-drive configuration.

As competition improved the breed, the performance of road cars was progressing rapidly. The race cars were the road cars in most cases, and any improvements that could be found on the race car were immediately incorporated into next year's road car.

Duryea | 6.66 mph (10.6 km/h)

November 28, 1895 | Average speed of America's first auto race winner

America's first auto race had just two finishers, and was won by a car with a single cylinder engine that averaged just 6.7 mph for the shortened 52.3 mile distance from Chicago to Evanston and back.

A blizzard made for near impassable roads and though the average speed wasn't really indicative of the Duryea's performance on good roads, its win in such conditions helped convince the American public of the viability of the automobile for mission-critical tasks. As the event was run by the Chicago Times Herald newspaper, Duryea's triumph over adversity was well documented and the America-wide newspaper reports created many prospects for his just-formed Duryea Motor Wagon Company, kickstarting the American automotive industry.

Duryea's story of the race is retold here, and the original car has been recreated and is examined in detail in the above video from antique and custom auto specialist Bill Eggers.

Panhard & Levassor | 15.69 mph (25.25 km/h)

September 24 – October 3, 1896 | Average speed winner Paris-Marseille-Paris Race

Motor racing was becoming very important to sales in those early years as evidenced by the number of quality entries for the epic ten-day, 1,710 km Paris–Marseille–Paris race in February 1896. Entries included seven De Dion-Boutons (five gasoline powered tricycles and two steam powered cars); five Leon Bollées (four Léon Bollée tricycles and tandems plus an Amédée Bollée); four Panhard et Levassors; three Peugeots and two Delahayes, indicating the growing momentum of the industry. The race was won by a new 2.4 liter, 8 horsepower Panhard & Levassor (above) at an average speed of 15.69 mph (25.25 km/h). Panhard won more races than any other marque in the years 1894-1900.

Jeantaud Duc EV | 39 mph (63.13 km/h)

December 18, 1898 | Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat wins the first speed trials in Achères, France with Jeantead electric vehicle

On 18 December 1898, the very first speed record for automobiles was set when the French magazine La France Automobile held the world's first outright speed contest for cars, giving the fledgling automotive industry a simple and desirable goal – going faster than anyone had ever gone before.

The challenge was almost perfectly framed, requiring the application of advanced engineering ingenuity and devil-may-care bravery in the relentless pursuit of the title of "the world's fastest."

This was a time when newspapers delivered the world's news – radio had not yet been invented, and the newspaper publicity that speed contests generated from this point onward is hard to equate to today's world. It soon became obvious to the fledgling automobile industry that getting your name in an advert wasn't nearly as good as getting your name in the story.

This initial foray into outright speed saw the record broken five times in the subsequent four months, jumping from 63.13 km/h (39 mph) in December, 1898 to 105.26 km/h (65.79 mph) by April, 1899.

The fastest speed recorded in that magazine contest on December 18, 1898 was the Jeantaud Duc Electric Vehicle of Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat (subsequently known to newspaper readers as "the Electric Count") who covered a flying kilometer in 57 seconds for an average speed of 63.13 km/h (39 mph).

At that point in time, electric cars had an edge in speed over their petrol-engined rivals, a point not often recognized because EVs did not feature in the big city-to-city races of the day. This was almost entirely due to the difficulty they had replenishing energy reserves in provincial France.

Not a great deal is known about Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat's motivations, but prior to his first land speed record, he competed in many of the first autoracing events in history, and in all but one event in his racing career, he chose steam or electric propulsion methods.

Count Gaston's initial record was almost certainly set with a standard Jeantaud model and involved him covering one kilometer (0.62 miles) with a flying-start in 57 seconds for an average speed 62.78 km/h. A look at photographs of his car suggests he'd personalized the car and removed anything unnecessary – this was the high powered urban road car of 1898, and the "Electric Count" would have been a regular sight on Paris streets, enjoying his newfound recognition and status.

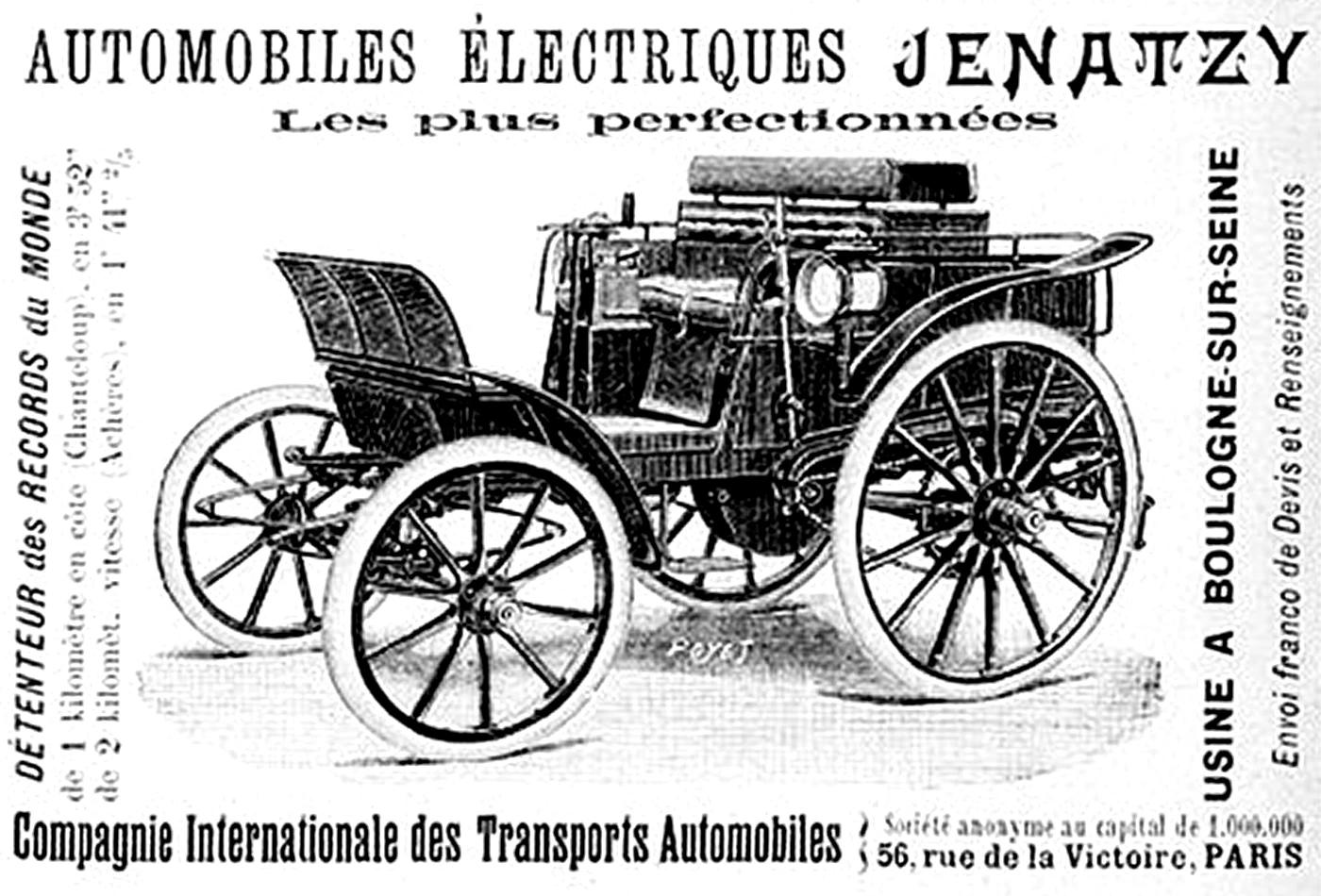

CGA Dogcart EV | 41.42 mph (66.27 km/h)

January 17, 1899 | Achères, France | First speed record challenge/broken

Count Gaston's speed record created a target at which others could aim, and it roused the interest of Belgian Camille Jenatzy. Jenatzy studied electrical engineering in Brussels before moving to Paris to work in the epicenter of the new and growing electric vehicle industry. Following the initial triumph of Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat, Jenatzy challenged him to a run-off and the date for the showdown was 17 January 1899.

Jenatzy arrived with a CGA Dogcart (some early styles of automotive models were referred to as "dogcarts" after the horse drawn carriages of the same description). Little information is available on the car other than that it was powered by one 80 cell Fulmen lead acid battery and that it established a new record of 66.7 km/h (41.42 mph).

Jeantaud Duc EV | 43.6 mph (70.17 km/h)

January 17, 1899 | Achères, France | Record reclaimed same day

Chasseloup-Laubat responded in his Jeantaud, running 70.17 km/h (43.6 mph) and yet another record was established. As battery technology of the day was primitive in comparison to today, both cars had "spent" their batteries and no further runs were possible. Hence Jenatzy had held the record for just a few minutes, the Electric Count prevailed on the day ... but not for long.

CGA Dogcart EV | 49.93 mph (80.35 km/h)

January 27, 1899 | Achères, France | Jenatzy again

Ten days after the January 27 run-off, Jenatzy returned to Achères with the same CGA Dogcart of his own manufacture and ran a speed of 49.93 mph (80.35 km/h), breaking the speed record for the second time. Jenatzy's understanding of engineering alongside his prowess as a driver was to see him go on to become one of motorsport's greats.

Jeantaud Duc Profilee EV | 92.7 km/h (57.59 mph)

March 4, 1899 | Achères, France | The 'Electric Count" reclaims title

The battle was now all consuming for both Jeantaud and Jenatzy, and on 4 March 1899, six weeks after Jenatzy's record, the Electric Count rolled out a new car dubbed the "Jeantaud Duc Profilée," which included the first notion of aerodynamic efficiency in an automobile. The drag coefficient was no doubt reduced with the greatest gain coming from a much smaller frontal area and the Count took the record back with a run of 92.7 km/h (57.6 mph).

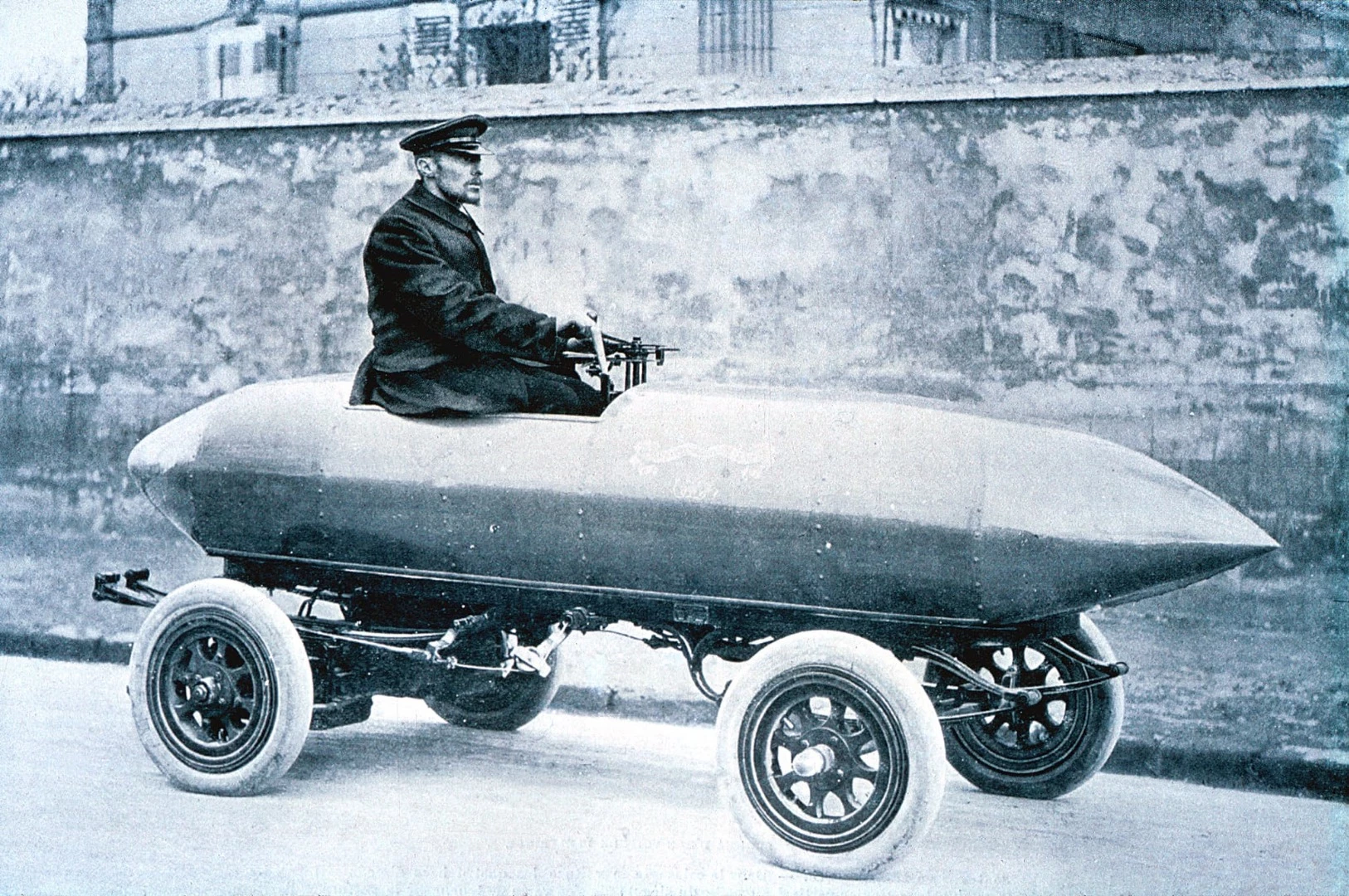

La Jamais Contente (EV) | 65.79 mph (105.26 km/h)

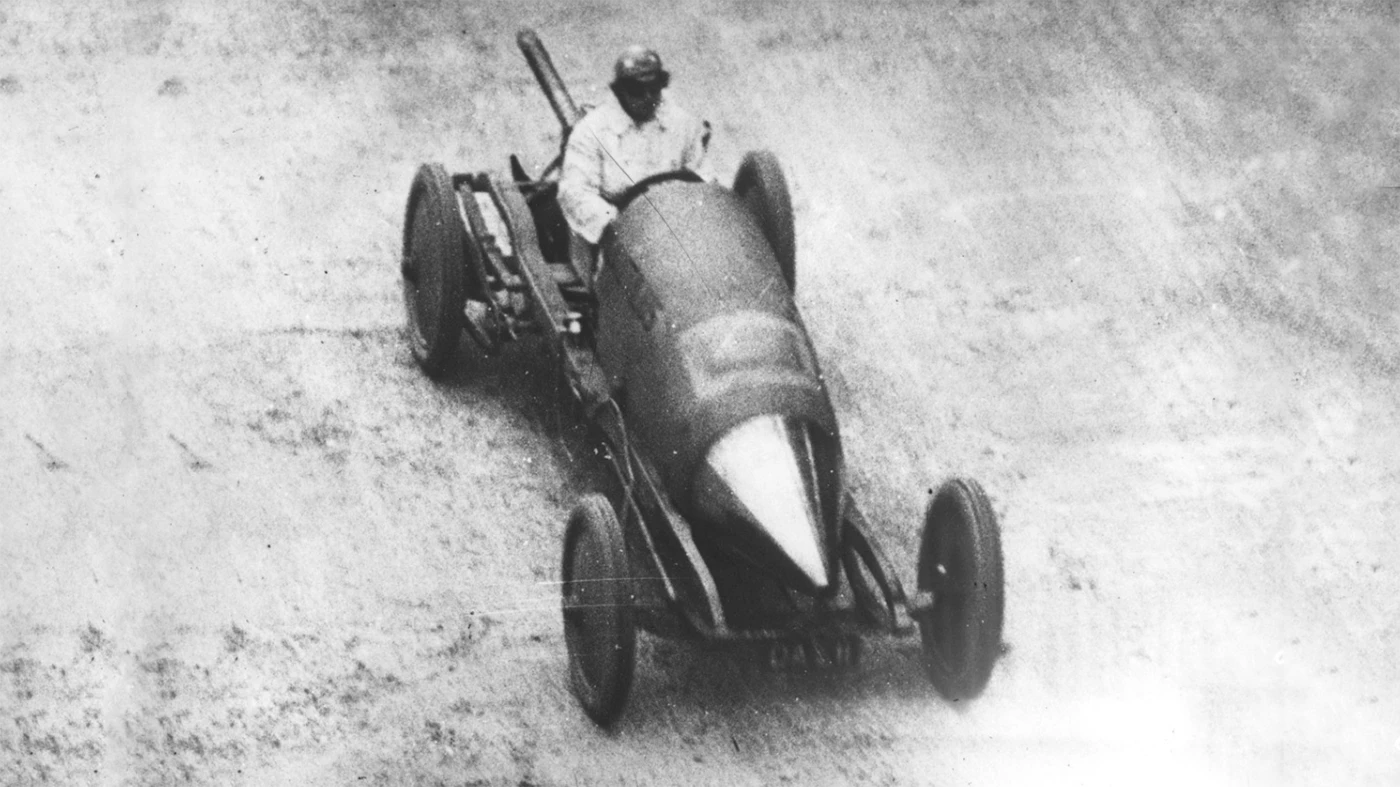

April 29, 1899 | Achères, France | Jenatzy breaks record a third time

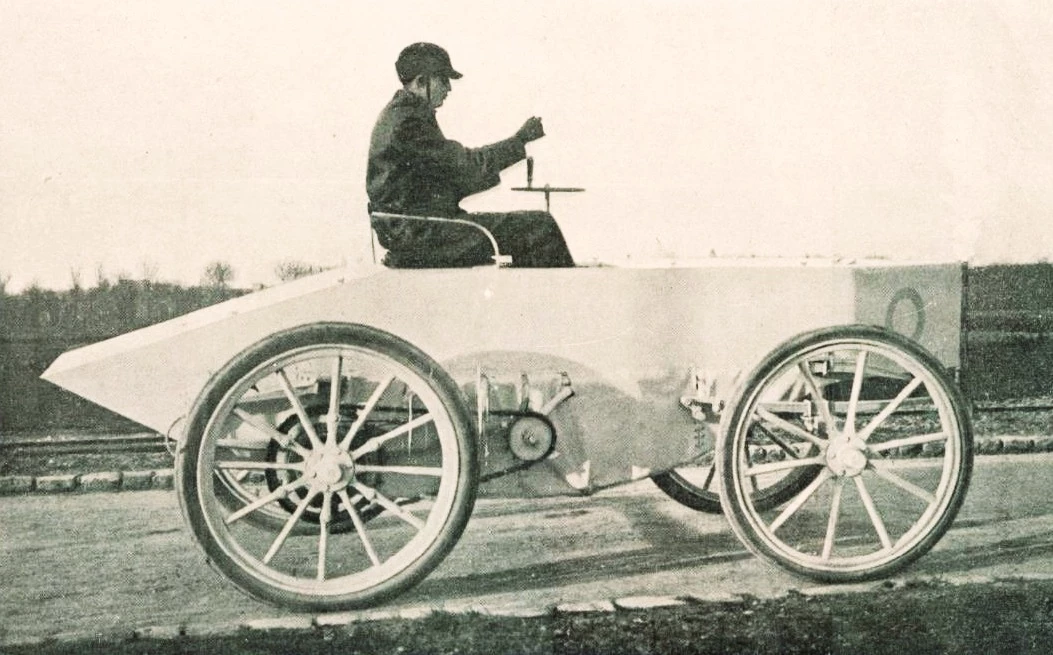

Jenatzy had also been working on a new car, a torpedo-shaped electric vehicle with extensive use of "partinium" – a strong, lightweight and expensive alloy made of aluminum, copper, zinc, silicon and iron that had not been previously used in a car. This was the first "purpose built" car for a land speed record and was appropriately named "Jamais Contente" (Never Satisfied). The car used two direct drive Postel-Vinay electric motors for a total of 68 hp and it was interesting to note that both contenders for the initial record had quickly realized that aerodynamics would play a part in the ultimate outcome. Jenatzy finally captured the speed record with a run of 65.79 mph (105.26 km/h).

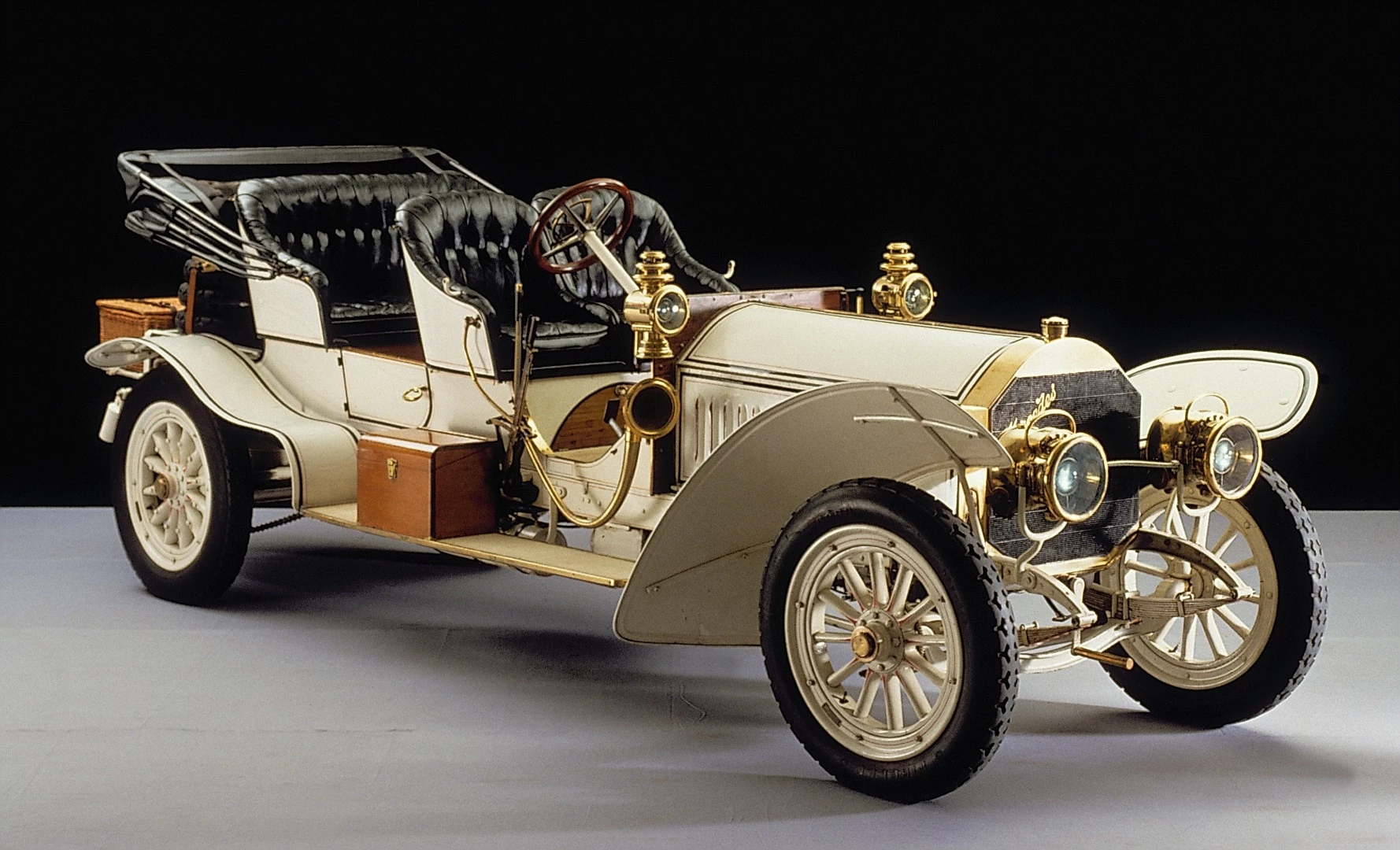

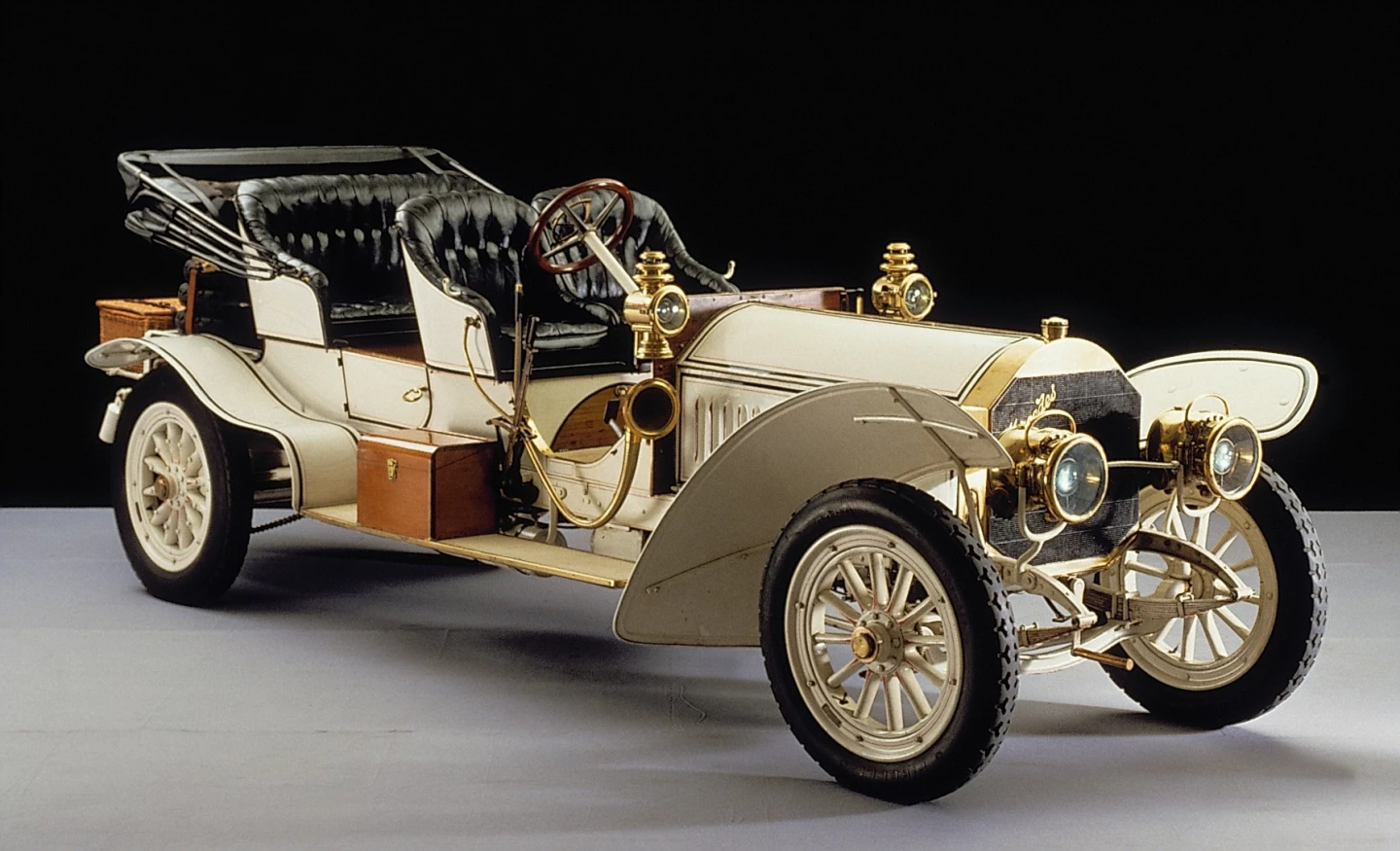

Mercedes 35 hp | 36 mph (58 km/h)

March 25-29, 1901 | Nice, France | Nice-Salon-Nice winner average speed

The Mercedes 35 hp was the first time the Mercedes name appears in automobile production, though Austrian diplomat and entrepreneur Emil Jellinek did have a prestige auto dealership in Nice named Mercedes. Jellinek's prestige car dealership ran a racing team to promote its wares, and Jellinek asked DMG (Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft) to produce 34 cars of his own design. His concept was to lower the centre-of-gravity of the cars at the same time as lengthening the wheelbase and widening the car, all resulting in much better roadholding. The design that finally emanated from the drawing boards of designed in 1901 by Wilhelm Maybach and Paul Daimler is quite distinct from the stagecoach layouts inherited from the horse-drawn era, which had dominated automobile design prior to then. Most agree that this vehicle was the first modern car. I believe it should also be regarded as the world's first sports car. It was conceived with motorsport in mind, won countless races, and the entire species immediately evolved in that direction. This is the perfect example of competition improving the breed.

Jellinek's car and the name he chose for his business was the same pet name he had for his daughter: Mercedes. The car's racing debut in January 1901 at Grand Prix du Sud-Ouest was unspectacular, with teething issues perhaps resulting from the first of the 34 cars being delivered on 22 December 1900. The next competitive outing in March at Nice Speed Week produced a clean sweep of the Nice-La Turbie event, raising the average speed from the previous best of 19.4 mph (31.3 km/h) to 31.9 mph (51.4 km/h) and the Mercedes was reportedly timed at 86 km/h during the race. The Mercedes also won the 1901 Nice-Salon-Nice race in the hands of Wilhelm Werner, averaging 36 mph (58 km/h) during the week of automotive festivities. This car went into series production as the Mercedes 35-hp and would have been the fastest road car in the world at that time, with state-of-the-art roadholding. It was the first production car one sat "in" rather than "on".

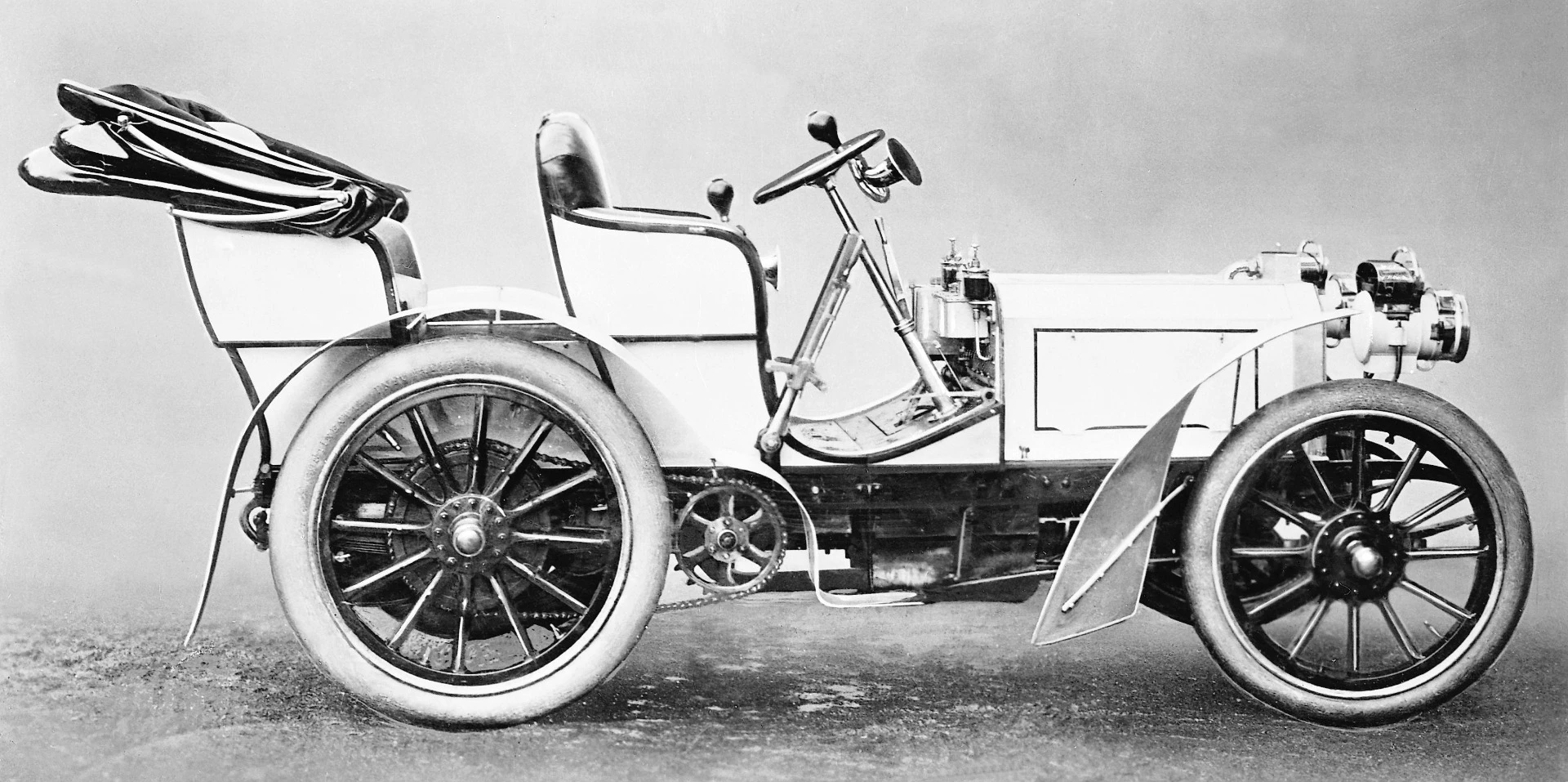

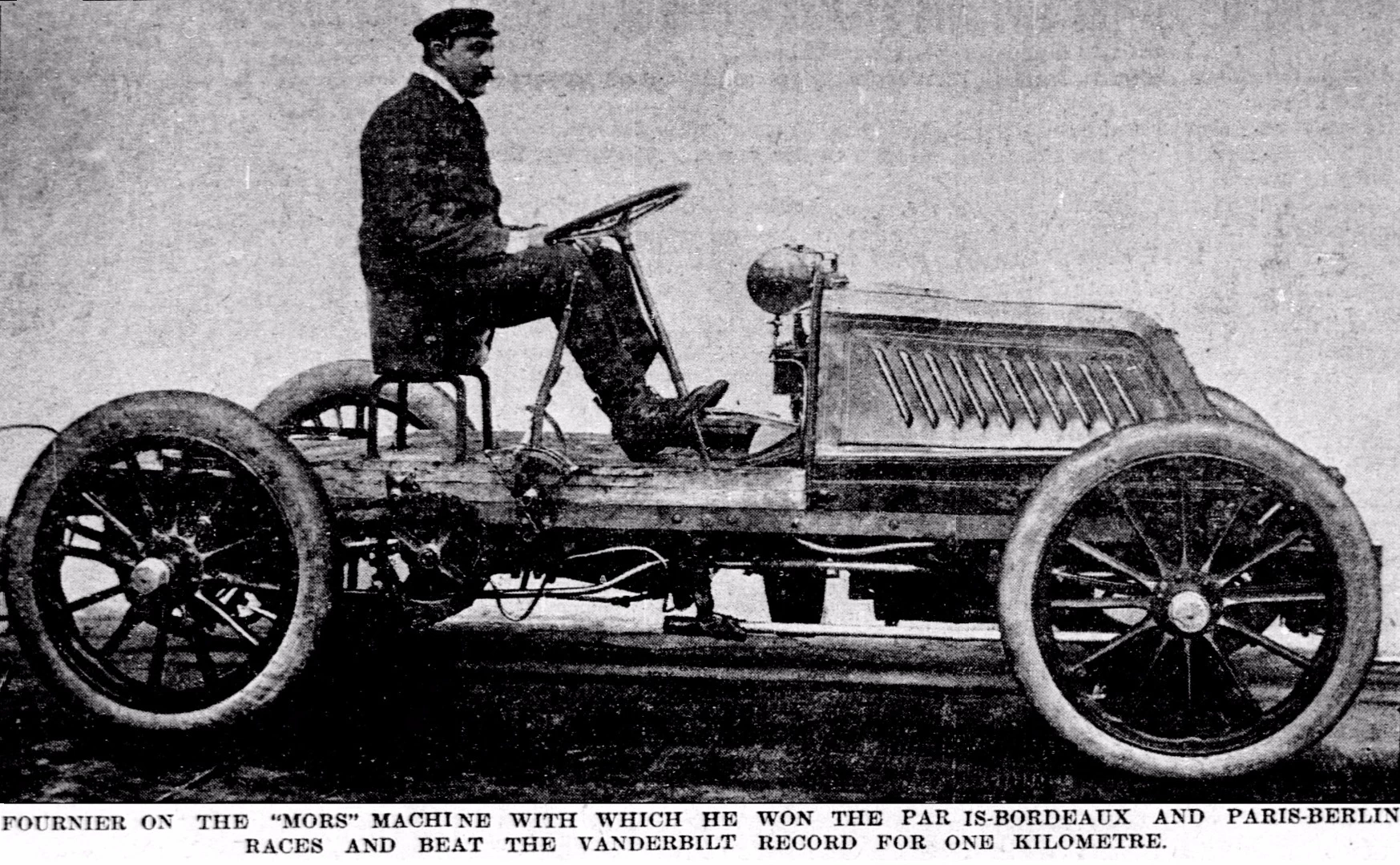

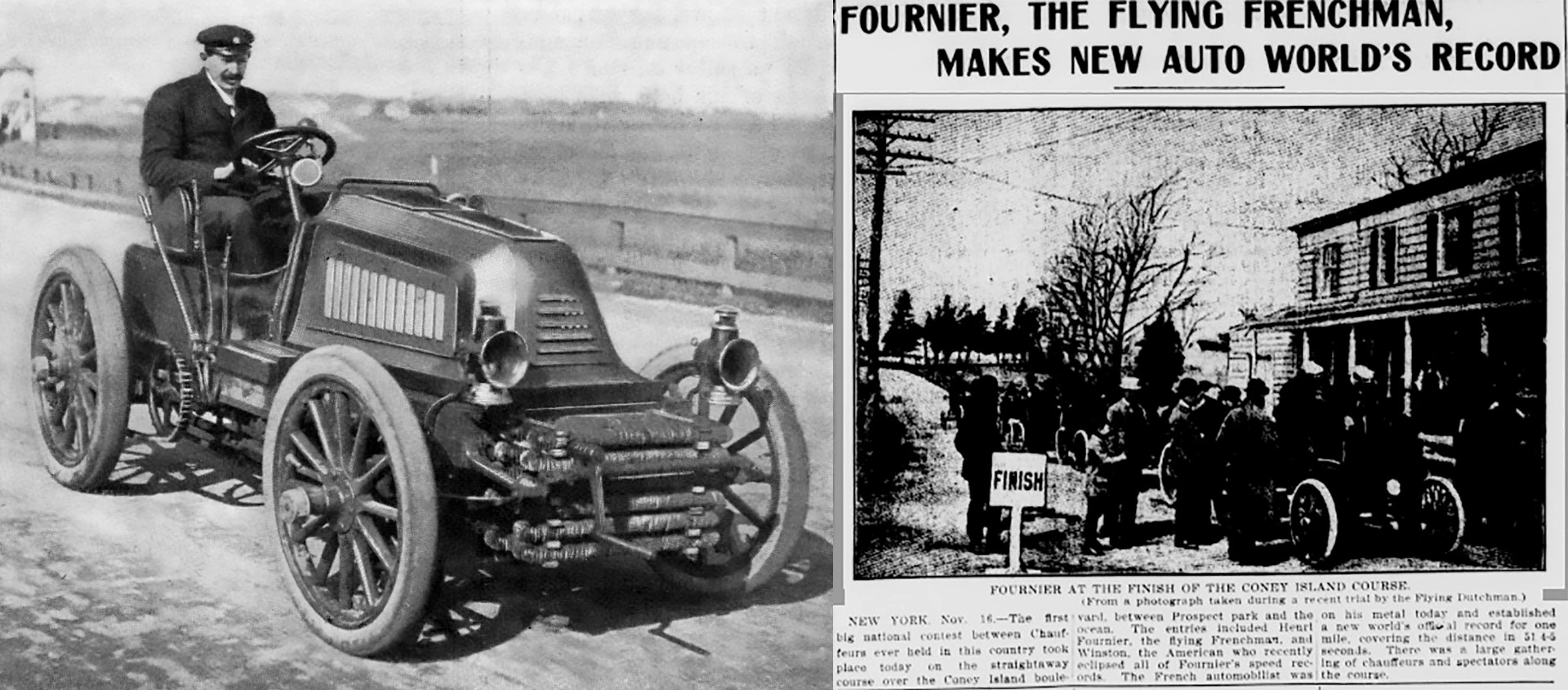

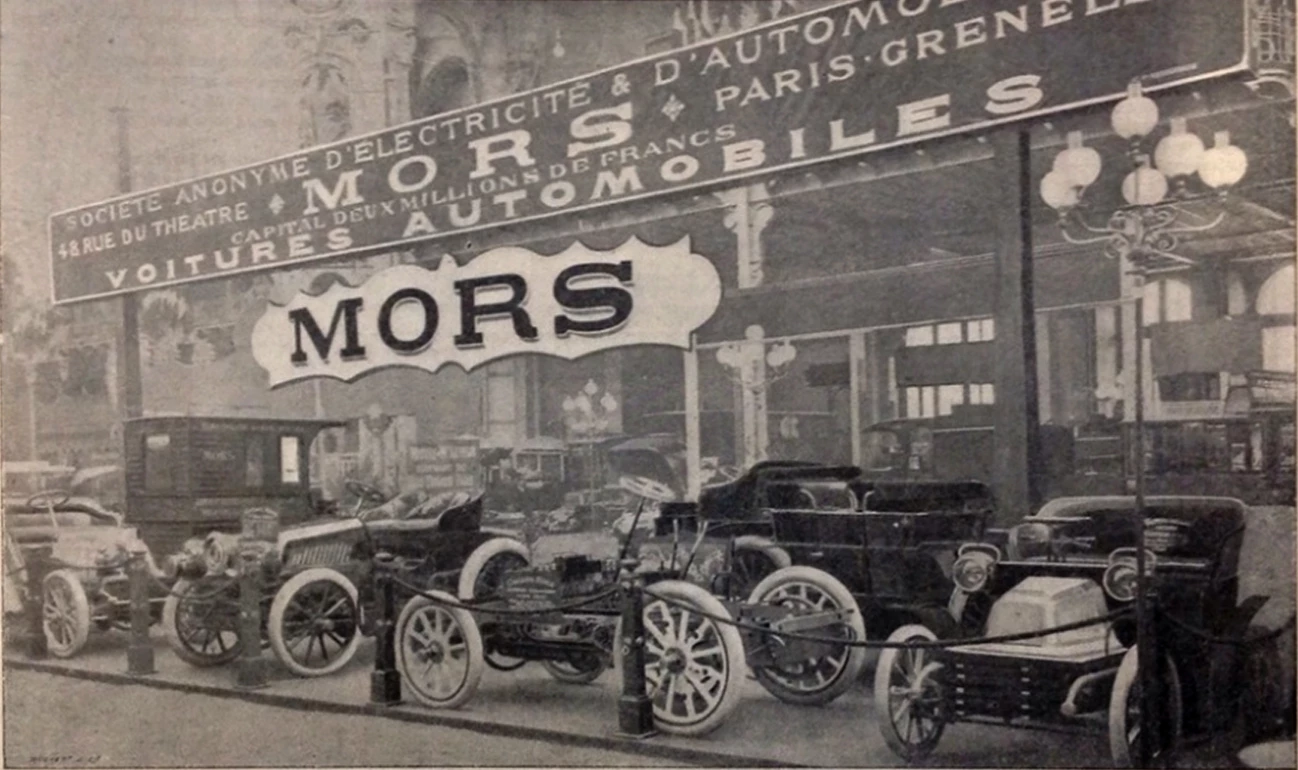

Mors | 69.5 mph (111.8 km/h)

November 16, 1901 | Coney Island Boulevard, New York

We're not sure why this record hasn't previously been recognized, but on November 16, 1901, Mors factory driver Henri Fournier, during a promotional visit to America, set a time of 51.8 seconds for the flying mile, giving him a speed of 69.5 mph (111.8 km/h) and what was claimed at the time to be a world record. That's a clipping from the Los Angeles Herald at right above, and the image at left is of Fournier in his Morz Type Z and came from this excellent coverage of events in the Digital History project.

Gardner-Serpollet "Easter Egg" | 75.06 mph (120.8 km/h)

April 13, 1902 | Promenade des Anglais, Nice Speed Week, France

The French Serpollet Brothers were steam automotive industry pioneers and competed in all the early European races, having four cars in the inaugural 1894 Paris-Rouen event. Leon Serpollet patented his flash boiler in 1896, enabling a more practical and convenient power unit, and in 1898 the brothers secured backing from American Frank Gardner for the formation of the Gardener-Serpollet Company, which began producing cars in 1900. Leon drove the car that would put his company in the history books, clocking 120 km/h (75 mph) on 13 April 1902 over the flying kilometer on the Promenade des Anglais during Nice Speed Week.

It wasn't a standard car, but more a rolling development prototype, being the culmination of a several-year project evolved from the original Easter Egg design shown above, the shape being responsible for its name in French, "Œuf de Pâques." The bow-cutter aerodynamic shape of the car is rarely seen, but the car proved that steam cars were capable of speeds beyond today's speed limits 114 years ago. All previous photos I've seen of this car show it as an Easter Egg design, though all of them were taken in Paris where Serpollet was a well recognized regular motorist about town in the car, which must certainly have been the fastest road car in the world at the time.

Mors | 76.08 mph (122.4 km/h)

August 5, 1902 | First internal combustion engine to hold the car speed record

This was the first car powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE) to hold the automobile speed record, with electric and then steam having led the way before August 5, 1902 when speed trials were held near Chartres, France.

The driver on this occasion is of equal interest, being American William Kissam Vanderbilt II, the great grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, and a noted racer and sportsman of the day. Vanderbilt could buy whatever he wished in order to pursue his greatest passion, and in 1902 he chose a 60 hp four-cylinder 9232 cc Mors Model Z, driving it in the Paris-Vienna race in late June. Knowing how fast the car was during the open sections of the Paris-Vienna race, he realized the opportunity to set a record with it, which he did. Willie went on to found the famous American Vanderbilt Cup races, serve in the United States Navy (in his own yacht which became USS Tarantula for the duration of WWI) and he won the Sir Thomas Lipton Cup in 1900 with his new 70-foot yacht named Virginia after his wife, the heiress of the man who discovered the famous "Comstock Load" gold deposit. Willie K will appear again in this story.

For Mors, the record was yet another of many achievements for the marque at this time, with wins in the 1901 Paris-Bordeaux and 1901 Paris-Berlin great races, making the Mors Type Z the fastest road car in the world by the later months of 1902. The above image comes of a Revs Institute article on the car and there are some awesome detail shots of a fully restored 1902 Mors Type Z. It is a beautiful thing.

Mors | 76.6 mph (123.3 km/h)

November 5, 1902 | Mors improves its own record |Dourdan, France

Just three months later on November 5, 1902, Henri Fournier used a stripped down Mors Type Z to push the speed record to 76.6 mph, reclaiming the record he had seemingly held during the previous year. Fournier had also driven in the 1902 Paris-Vienna race several months earlier and had dominated the first leg of the event with an average speed of 70.8 mph (114 km/h) to Provins, but a gear shaft broke when he was leading. In only beating Vanderbilt's record by the narrowest of margins, the opportunity was there to continue to create publicity for the brand by breaking the record again.

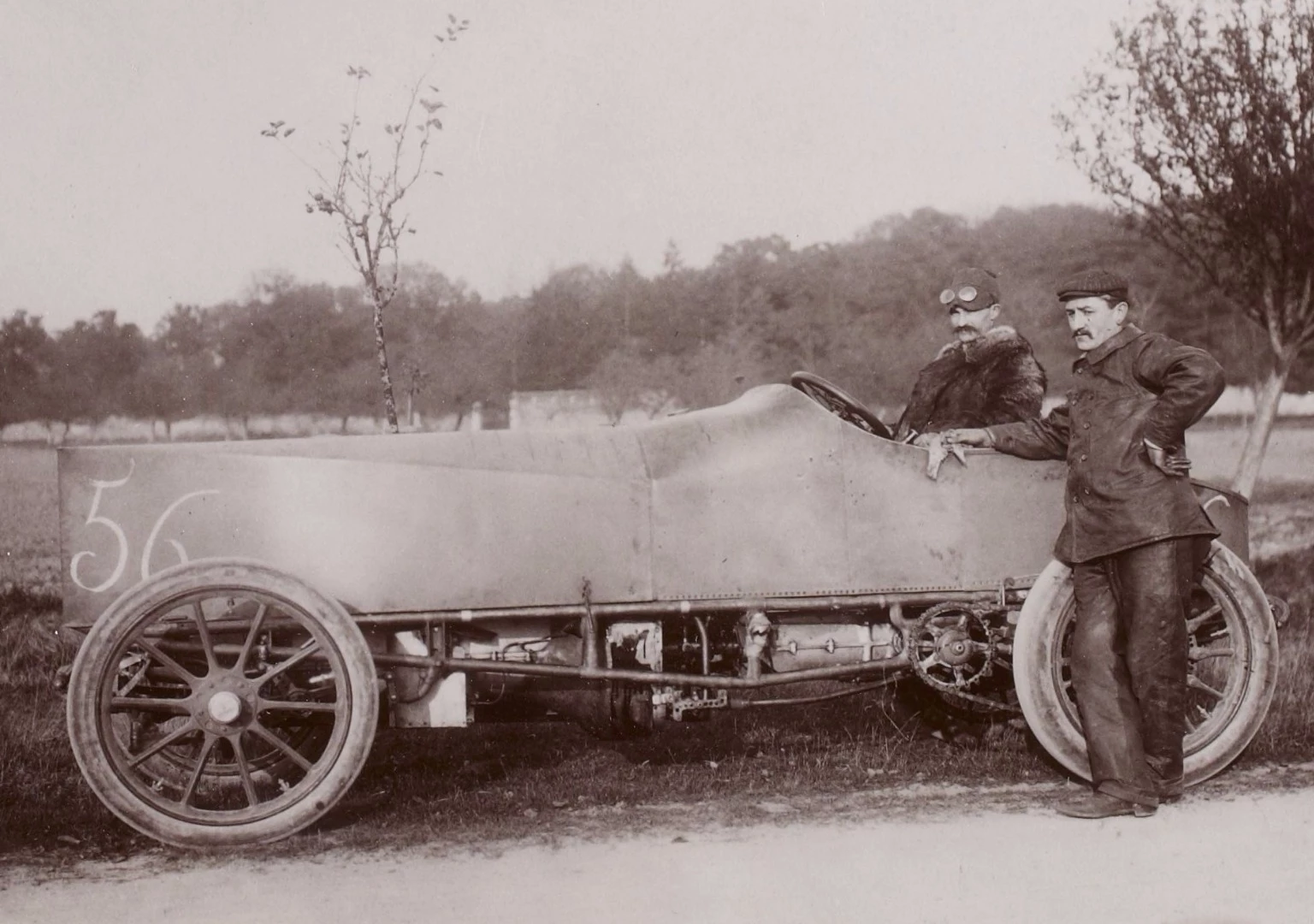

Mors | 77.1 mph (124.1 km/h)

November 17, 1902 | Mors improves its own record |Dourdan, France

On 17 November, 1902,Maurice Augières used Fournier's Mors Type Zto push the speed record to 77.13 mph (123.41 km/h). That's Maurice pictured above with his passenger or riding mechanic. The riding mechanics had an even more precarious existence than the driver without the glory or pay, and as this article from AutoWeek points out, it must have been an interesting time for them:"The Type Z Mors is credited with being the first automobile with four-wheel shock absorbers. The engine's great reciprocating masses at certain speeds match the springs' harmonics and cause the Mors to 'gallop.' For a modern driver, sitting high up in the exposed driver's seat, the mere thought of traveling at over 70 mph on this contraption is daunting."

The car in which both Fournier and Augières broke the record was sold to an English racer after its record breaking runs. His name was Charles Rolls, and in May the following year (1904), Rolls met Henry Royce. Just two years after Rolls purchased this Mors, the Rolls-Royce 10 hp was shown at the Paris Salon (December 1904).

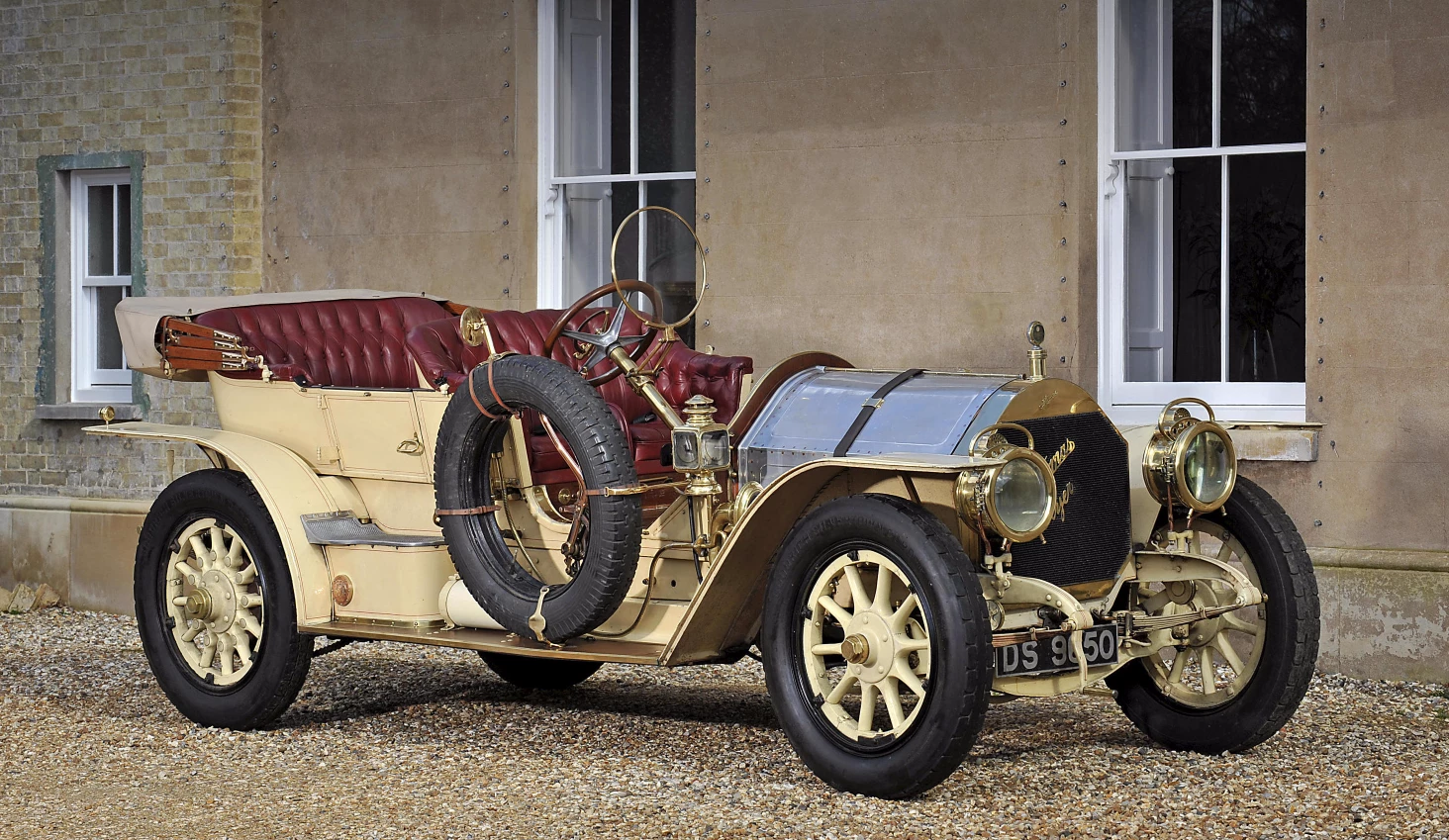

The quality of the Mors road cars was of an equally high standard and the 1904 Mors 24/32-hp Roi des Belges Touring car pictured above would have been one of the fastest comfortable touring cars on French roads at that time.

Mors | 65.3 mph (105.1 km/h)

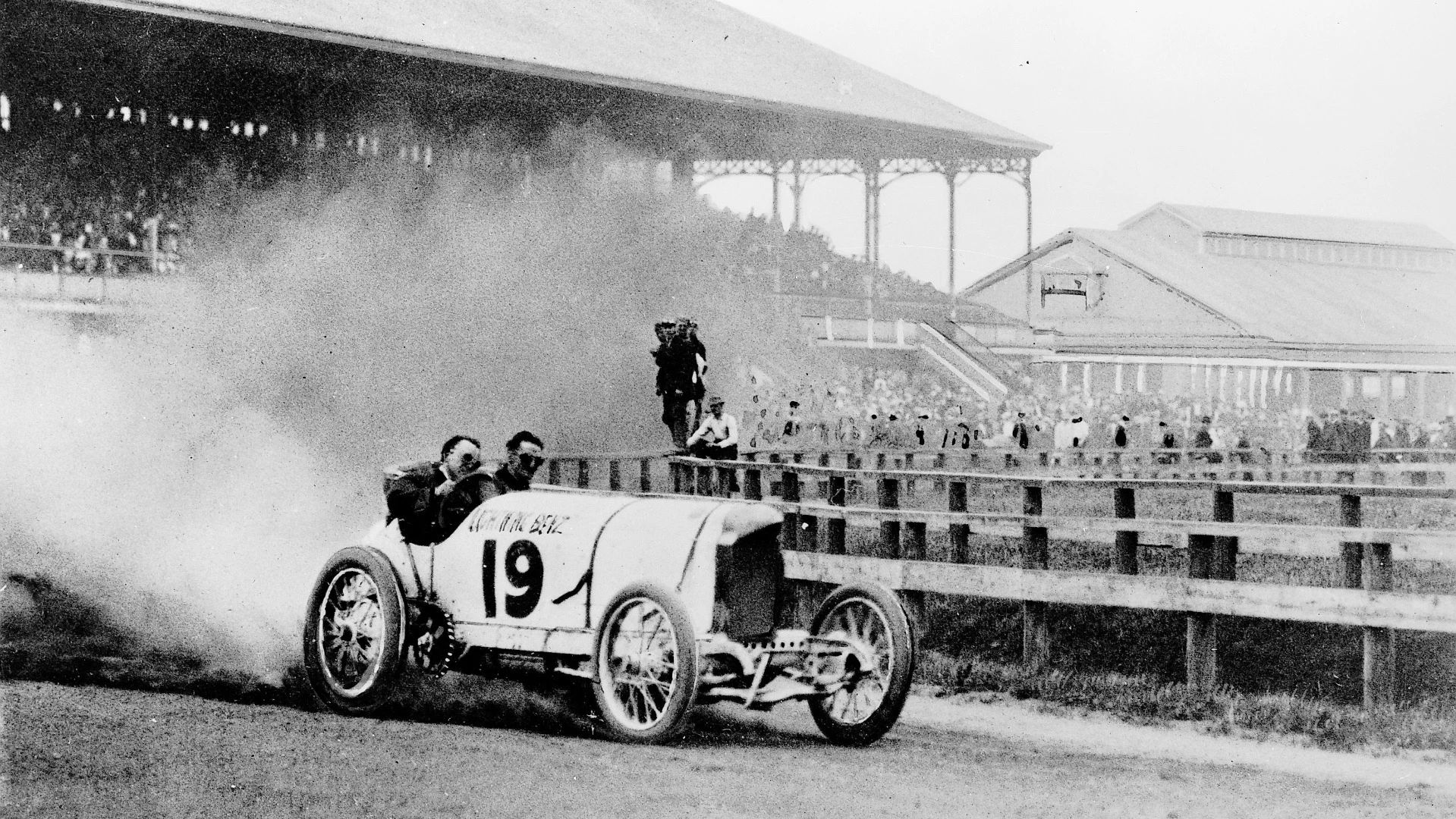

May 24, 1903 | Paris-Madrid Race (average speed to race cancellation)

The famous 1,307 km (812 mile) Paris-to-Madrid race of 1903 made global news for all the wrong reasons, primarily that the speeds of the latest cars were quickly becoming too fast for public roads. Public interest was massive, with no crowd control and spectators lining the 800 mile "racetrack" that was still in use by citizens during the race. It was also a hot day, with the cars throwing up clouds of dust which reduced visibility for both drivers and spectators.

Massive public interest saw 100,000 attend the 2 am race start 20 km from Paris, and the road to Bordeaux was lined with people as cars went through. As trying to pass made things even more difficult for the spectators on the narrow roads, the 224 starters were released one minute apart over four hours.

Though more than 100 races had been run on European public roads prior with relatively few mishaps to non-combatants, this race was pure carnage for all, with 122 of the 224 starters failing to reach Bordeaux and three spectators and five racers dead. The race was stopped, the global public had its first real debate about the rights of citizens to safe passage on public thoroughfares and racing on public roads was banned. The second historically-important debate about public safety in motorsport was precipitated just a 100 kilometers from the course of this event at Le Mans in 1955, when one race car killed 84 and injured 120.

The same roads used in the first leg of 1903 Paris-Madrid race led from Paris to Bordeaux, and had been largely used for the 1901 Paris-Bordeaux race, with the winning Mors (Fournier) averaging 53.0 mph (85.3 km/h) and the second placed Panhard averaging 49 mph (78.8 km/h). The same roads had also been used in the 1899 Paris-Bordeaux race when Fernand Charron led home a Panhard 1-2-3-4-5 finish at an average speed of 30 mph(48.2 km/h).

The speeds achieved by those who led the race into Bordeaux bear testimony to the quantum leap in top speed of the faster road cars in this period.

Fernand Gabriel's Mors Type Z was the fastest to Bordeaux with an average speed of 65.3 mph (105.1 km/h) with Louis Renault's Renault not far behind with a 62.3 mph (100.2 km/h) average. Louis would reach Bordeaux to the later confirmed rumors that his brother had died in a crash behind him.

In addition to the dry rutted roads and bad visibility, with banks of unprotected spectators just meters away, it's also worth considering the woefully inadequate brakes of the era –front wheel brakes were still a decade into the future!

Imagine trying to stop a car from 70 mph on a dusty dirt road with only rear wheels brakes and overwhelmed suspension? Consider too, the wandering livestock in adjacent fields, and dogs and horses spooked by the fire-breathing unmuffled 10 liter projectiles and ... it had to happen sooner or later and it all happened on 24 May, 1903.

On the straights, the faster cars were now all running within a few miles per hour of the automobile speed record with brakes and suspension trailing behind in development compared to the motors.

Mors had added pneumatic suspension with the Type Z, but the suspension of most cars in the event had friction damping at best. The Mors was unquestionably the fastest road car in the world at that time. It had set four of the last five speed records, and exactly the same cars were in this race.

The first five cars to Bordeaux in 1903 all averaged remarkable speed under the conditions: Mors (65.3 mph), Renault (62.3 mph),Mors (59.1 mph),De Dietrich (58.2 mph), Panhard (57.9 mph) and Mercedes (57.7 mph).

By comparison, the 1901 race on the same roads was won at 49 mph, the 1899 race at 30 mph and the 1895 race at 15.2 mph, meaning average speeds doubled in the four years from 1895 to 1899 and more than doubled in the next four years.

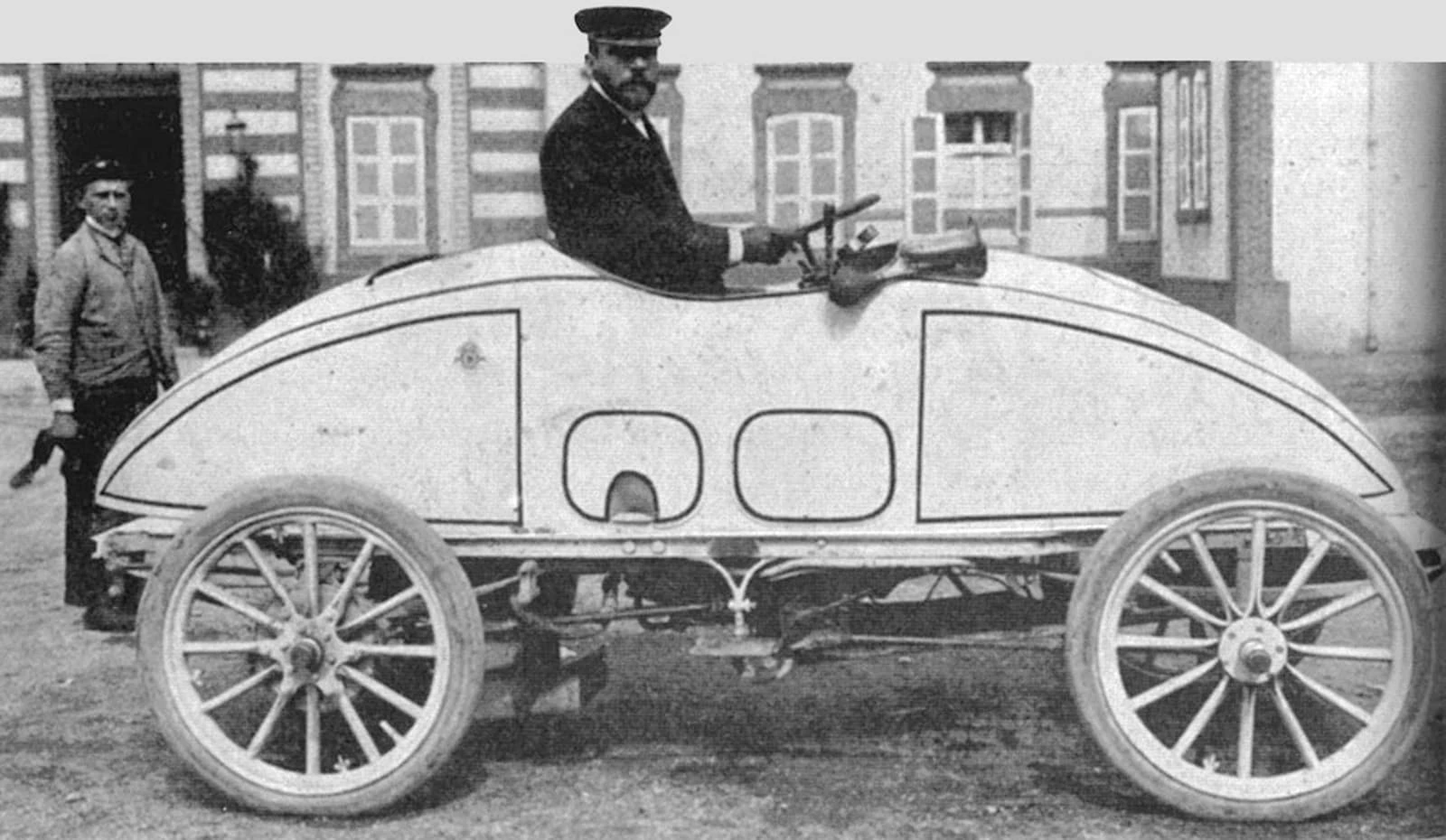

Gobron-Brillie | 83.5 mph (134.3 km/h)

July 17, 1903 | Ostende, Belgium| First car over 80 mph

American Arthur Duray was the first man to drive at more than 80 miles an hour, when the veteran professional driver covered the flying kilometer in 26.8 seconds at Ostende Belgium on 17 July 1903, setting a new speed record of 83.47 mph (134.3 km/h) in his Gobron Brillie.

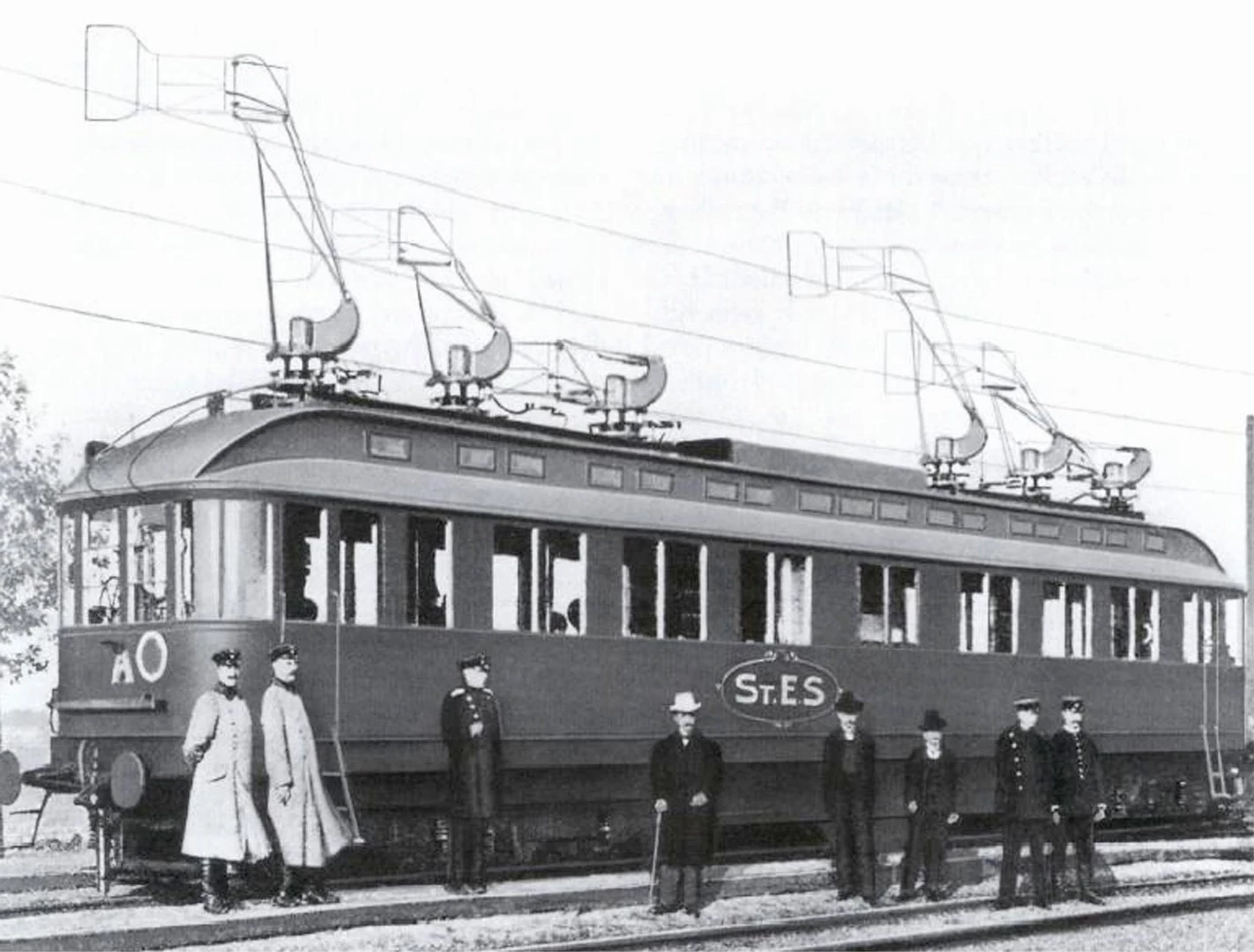

AEG Electric Railcar | 130.7 mph (210.3 km/h)

October 28, 1903 | Marienfelde, Germany | Outright land speed record

With the car speed record fast closing on the steam train's speed record, the next contender came from left field, as experimentation with the electric train pushed the world land speed record out of reach of the automobile once more.

A 23 km section of electric rail infrastructure was created from a former military railway by the German Society for the Study of Electrical Rapid Transit, a consortium led by General Electric, Siemens & Halske, the industrial giant Krupp and several major German banks.

The test track played host to two competing electric drive systems for the 50-person trolley cars that were constructed – one railcar was fitted with three-phase AC electrical equipment supplied by AEG and the other with similar equipment supplied by Siemens & Halske. Both vehicles exceeded 124 mph (200 km/h), with the Siemens & Halske railcar setting an initial record of 126 mph (203 km/h) and eventually reaching 128 mph (206 km/h). On 28 October 1903, the AEG railcar was timed at 130.7 mph (210.3 km/h), a new absolute land speed record.

Gobron-Brillie | 84.7 mph (136.4 km/h)

November 5, 1903 | Dourdan, France

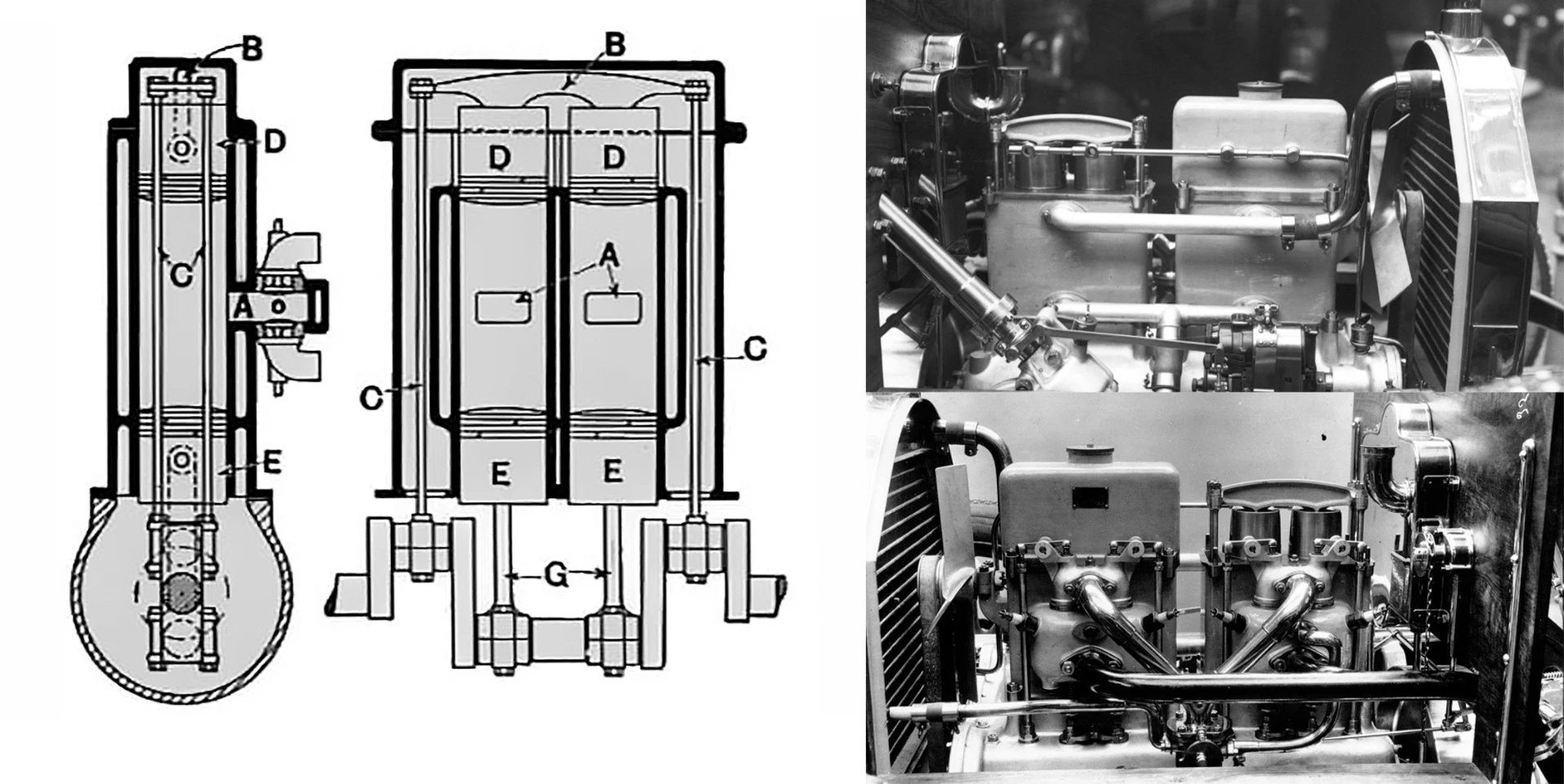

Duray did it again on 5 November 1903 in the same car, pushing the new car speed record to 84.73 mph (136.36 km/h) with the unconventional Gobron Brillie motor proving its mettle once more. Eugene Brillie had developed an opposed-piston engine in which each cylinder has a piston at both ends, and no cylinder head. The engine powered the company's road cars in several versions, the largest of which was an 11.4-liter six-cylinder producing 60/75 hp, but for the purposes of this contest, the engine was enlarged to 13.5-liters. It also ran on alcohol.

Wright Brothers Flyer | 6.7 mph (10.9 km/h)

December 17, 1903 | First flight

The first sustained and controlled, heavier-than-air, powered flight took place at 10:35 am at Kittyhawk, North Carolina. The Wright Flyer flew just 120 ft (36.6 m) in 12 seconds, at an average speed of 6.7 mph (10.9 km/h). Despite the skies being opened at Kittyhawk, the outright world speed record and the land speed record remained one in the same for many decades after Orville Wright's maiden flight, as planes were initially not as fast as cars, and the sustained number of automobile speed record attempts pushed the automobile ever faster.

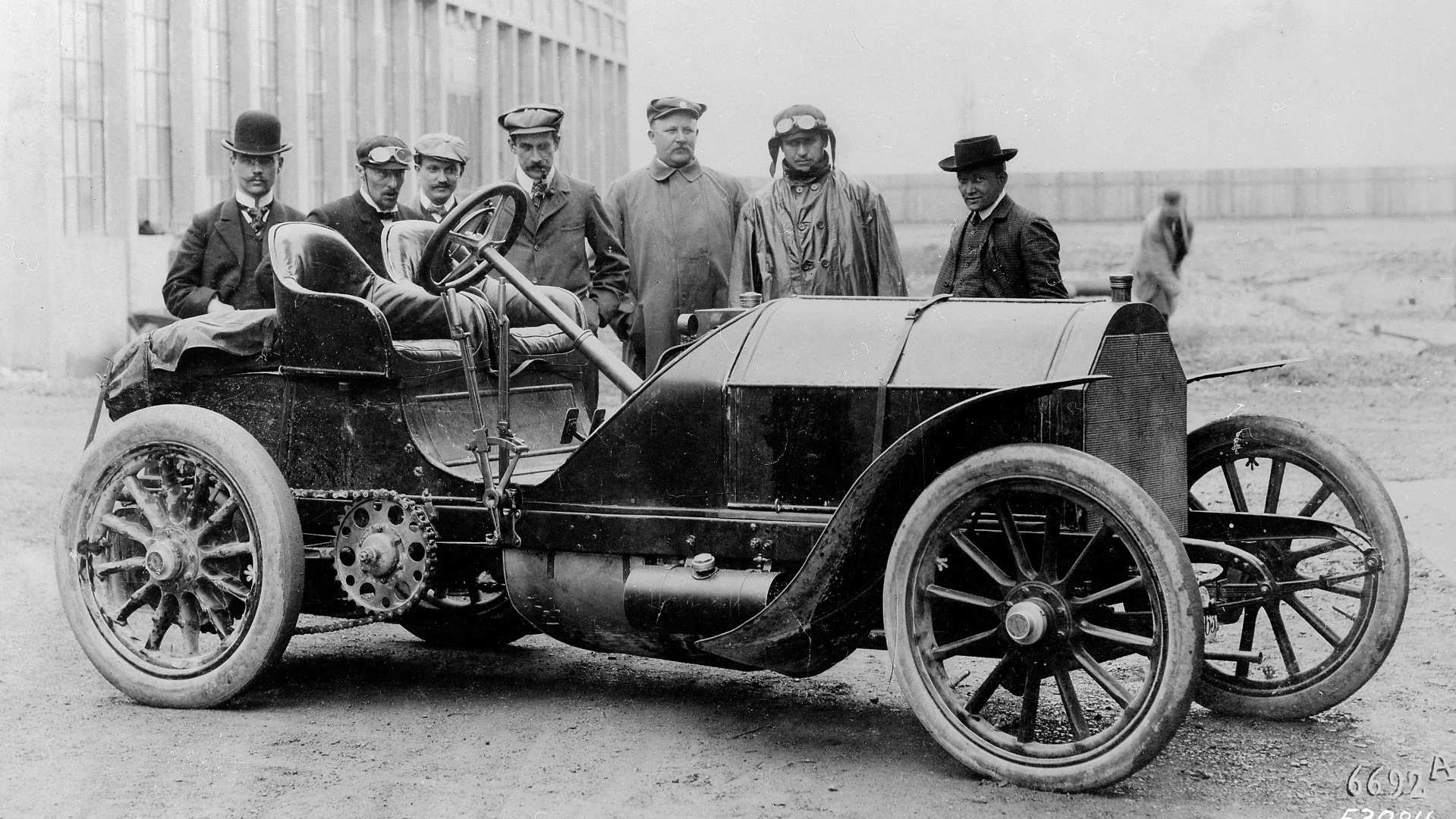

Ford | 91.4 mph (147.0 km/h)

January 12, 1904 | Lake St. Clair, USA | First car over 90 mph

Henry Ford reclaimed the record for America again when Barney Oldfield took Henry Ford's 999 to 91.37 mph (147.05 km/h) across a frozen lake bed on 12 January 1904. Barney became the first person to travel at over 90 mph other than by rail, and he did so using the brutal 1156 cu.in.(18.9 L) with its four bucket-sized pistons each firing 350 times every mile. At 1,200 rpm, the 999 was geared for 100 miles an hour.

The Henry Ford alliance with Barney Oldfield was fortuitous for both parties. Oldfield launched a glorious career in motorsport (and appears again in this very story), while Henry gained impetus in his ultimate quest using the record to propel him towards global recognition in many spheres. The full story is in the video below from Racing in America.

Mercedes Simplex 90 PS | 92.3 mph (148.5 km/h)

January 27, 1904 | Daytona Beach, Florida | Vanderbilt takes the record again

Just 15 days after Barnie Oldfield drove Ford 999 to a record, Willy K Vanderbilt grabbed the crown back at Daytona Beach, this time with a Mercedes 90 hp car. Vanderbilt's speed pushed the record to 92.3 mph (148.51 km/h) and though he took both his Mors and the Mercedes 90 hp to Daytona, it was the Mercedes that was the faster and took the ultimate honours. That's Willy heading off on the run that would take the record above (it's from the Vanderbilt Cup Races site which honors Vanderbilt's contribution to American automotive heritage and has an exceptionally well curated collection of images of the period, including Daytona Beach racing).

Gobron-Brillie | 94.78 mph (152.5 km/h)

March 31, 1904 | Promenade des Anglais, Nice Speed Week, France

The annual mile sprint trials along the Nice (France) waterfront in 1904 saw Gobron-Brillié send its two leading drivers (Louis Rigolly and Arthur Duray) and two of the Paris-Madrid racers prepared for the infamous race of the previous year. Duray was considered the lead driver, but on 31 March 1904, he could only coax 88.76 mph (142.85 km/h) out of his car. Louis Rigollyclocked 94.78 mph (152.53 km/h) along the Promenade des Anglais and the world speed record belonged to the unconventional Gobron-Brillié once more.

Mercedes Simplex 90 PS | 97.3 mph (156.5 km/h)

May 25, 1904 | Ostend, Belgium

Baron Pierre de Caters is one of those larger-than-life figures from early motor racing. You rarely see him in a photograph without elegant attire, a magnificent moustache and a cigarette. The Belgian adventurer was a pioneer aviator, and raced speedboats and cars at an international level (5th in the inaugural 1906 Targa Florio) and he was always up for an adventure, taking the first planes to India in 1910.

On 25 May 1904 at Ostend in Belgium, de Caters drove his Mercedes Simplex 90 PS to yet another world record for the marque at 97.25 mph (156.5 km/h). That's the Baron in the center of the image with the pipe, and Camille Jenatzy second from left, who was by then a Mercedes factory driver.

Gobron-Brillie | 103.5 mph (166.6 km/h)

July 21, 1904 | Ostend, Belgium

On July 21, 1904 Louis Rigolly gave the Gobron-Brilliemarque its final chapter in this story when he covered a flying kilometre at 103.561 mph (166.665 km/h) in Ostend, Belgium, in the alcohol-burning 13.5 liter Gobron-Brillié. He covered a flying kilometer in 21.6 seconds on the same stretch of road in Ostend that had played host to de Caters record attempt. The car was the same car the team raced in the road races up until the Paris-Madrid race of 1903 which caused racing on public roads to be banned. The Gobron-Brillié team was always competitive in road races but the low-piston-speed engine design was particularly good for high speed runs, and it produced mankind's first measured flying kilometer that "cracked the ton" – the 100 mph barrier that had seemed an impossible goal 20 years prior was now reality. The time of 21.6 seconds gave Rigolly an average speed of 103.56 mph (166.6 km/h), still well behind the 130.7 mph (210.3 km/h) set by the AEG electric trolleycar the prior year. Within three years, that record too would be broken.

Darracq | 104.5 mph (168.2 km/h)

November 13, 1904 | Ostend, Belgium

French auto maker Darracq began producing cars in 1896, and by 1904 was seeking to heighten its profile with an attempt on the car speed record. Darracq produced a new 100 hp 11,259 cc four-cylinder car designed by Paul Ribeyrolles specifically for the land speed record attempt and on November 13, 1904, factory driver Paul Baras recorded a speed of 104.52 mph at Ostend in Belgium to take the record.

Ross Special Steam Car | 94.7 mph (152.5 km/h)

January 25, 1905 | Daytona Beach, Florida

The Ormond/Daytona Beach races were once an American institution, with the beach first used for unofficial racing in 1902. With organized meets from 1905 onwards, there were 15 land speed records set on the beach prior to cessation of activities there in 1935, when Sir Malcolm Campbell ran 276.82 mph (445.50 km/h). In 1935, racing for outright speed moved to the Bonneville Salt Flats.

Despite this illustrious history, there has never been a flurry of activity as intense as that witnessed in that first meeting on January 25, 1905 when three world record speeds were seen in 30 minutes. The flying mile world record was broken first by Louis Ross in a streamlined twin-engined steam-powered special (above and the yellow car in the inset image) of his own construction at 94.73 mph. Five minutes later that record was broken by Arthur MacDonald in his Napier (see below) with a speed of 104.65 mph, then Bowden's twin-engined Mercedes ran 109.76 mph (see below).

In researching this article, this car stood out as one of the most unappreciated in history for what it achieved both in terms of outright performance and the contribution to steam-powered locomotion. It still seems decades ahead of its time and clearly contributed greatly to the better known Stanley Steam Car which appears later in this story.

The low frontal area and sleek shape of the record car indicate a a leap in understanding of aerodynamics just as the Jeantaud Duc Profilee, Jamais Contente and "Easter Egg" had done just a few years earlier, but with a century of the study of fluid dynamics since then, we all intuitively now know it was another big step in the right direction.

The above YouTube clip from the King Rose archives shows the races on Ormond Beach that day. Ross was a steam pioneer and went on to form the Ross Steam Automobile company in 1906, manufacturing cars until 1909 when he began experimenting with and producing railway signal torpedoes. He died when one of the torpedoes exploded.

Napier L48 Special | 104.6 mph (168.4 km/h)

January 25, 1905 | Daytona Beach, Florida

The Napier is often written up to be the first car to be recorded at more than 100 mph, though clearly that isn't true. It also never held the Land Speed Record, which is another common misconception. The Napier is definitely a name that maintained a long association with speed well into the 1960s, supplying its Lion aero engine to Malcolm Campbell's Napier-Campbell Blue Bird of 1927, the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird of 1931, Segrave's Golden Arrow of 1929, and John Cobb's Napier-Railton and Railton Mobil Special, which set the record in 1939 and held it until 1964.

The Old Motor has an article and detailed images of this car which was used by Clifford Earp to win a 100-mile race on Daytona Beach on January 27, 1906 with a time of one hour, 15 minutes and 4 2/5 seconds – that's a healthy average of 80 mph (128.6 km/h).

Mercedes Special | 109.7 mph (176.5 km/h)

January 25, 1905 | Daytona Beach, Florida

Now we're not really sure why this privateer Mercedes didn't take the world land speed record for cars at Daytona (FL) on January 25, 1905 because it was timed by six stopwatches that all agreed to one tenth of a second, all under AAA supervision, and though it was excluded from the results of 1905 Florida Speed Week due to being over the 1000 kg weight limit, it met all the criteria for the world record by covering the flying mile in 32.8 seconds for an average speed of 109.65 mph (176.5 km/h).

The car was a standard 60 hp Mercedes with the frame extended to accommodate an additional Benz four-cylinder 60 hp engine, effectively creating a straight eight engine with 120 hp and enough grunt to push through the air faster than any automobile prior.

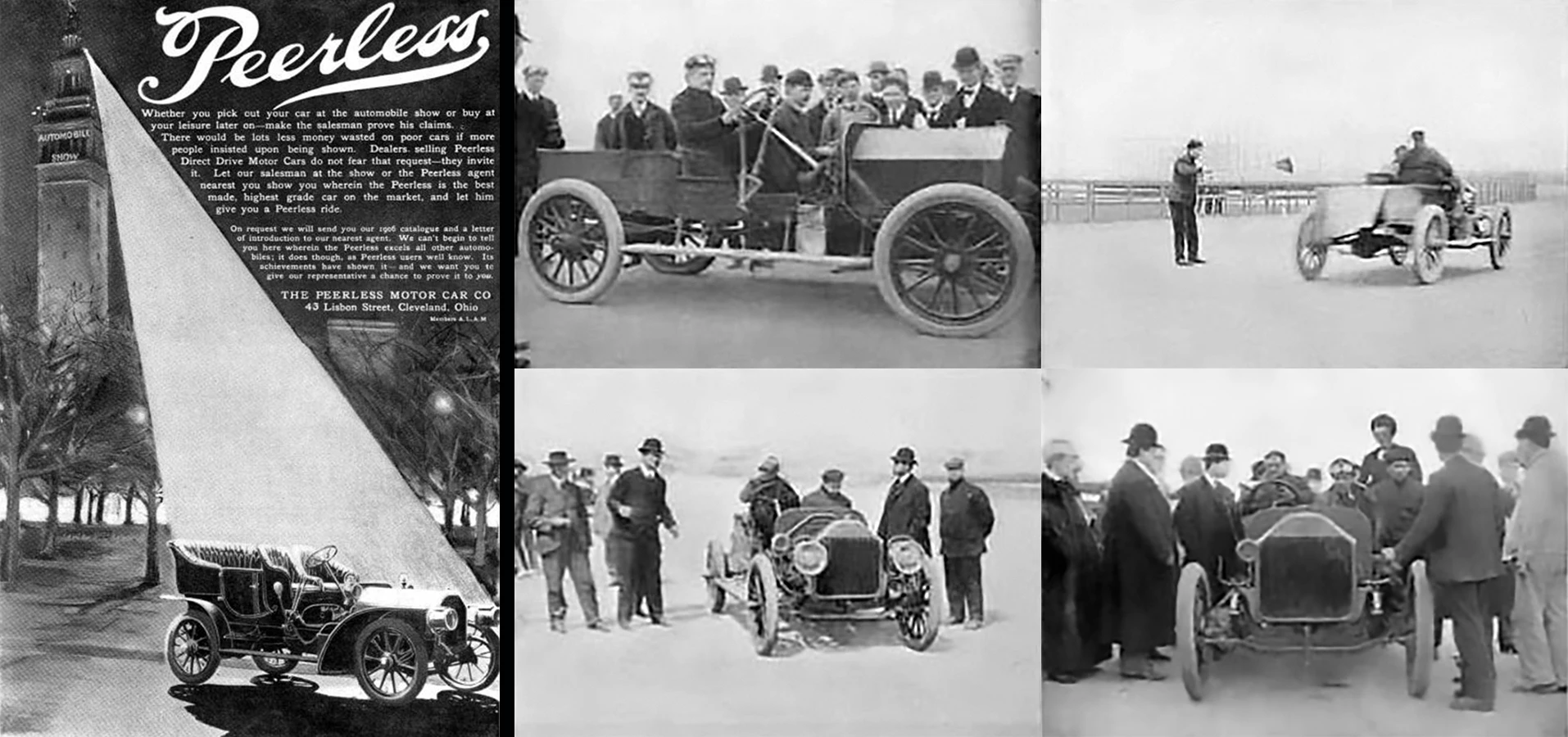

Peerless | 38.7 mph (62.3 km/h)

May 6, 1905 | Brighton Beach, New York | 1000 mile record

Peerless joined the ranks of automobile manufacturers setting records on March 6, 1905 when Peerless employee Charles Wridgway set a record for 1000 miles with a time of 25:50:01, at an average speed of 38.7 mph (62.3 km/h) on a one mile dirt oval at Brighton Beach in New York.

Decauville | 42.5 mph (68.3 km/h)

June 24, 1905 | Empire City, Yonkers, New York | 24 hour average speed

The establishment of a new record makes an alluring target and no sooner had Peerless created a 1000 mile record than it was broken again within two months. Using a one mile track at Empire City Racetrack in Yonkers, New York, 18-year-old Guy Vaughn, driving a 40-hp Decauville, set a new world 1000 mile record with a time of 23:33:20, and also a new record for covering 1015 and 5/8 miles in 24 hours.

Pope-Toledo | 34.5 mph (55.5 km/h)

July 4, 1905 | The world's first 24 hour race | Columbus, Ohio

The first 24-hour race in the world was held on 4/5 July 1905 in Colombus, Ohio and named the 24 Hours of Columbus. The race was won by the Soules brothers in a Pope-Toledo, covering a distance of 828.5 miles for an average speed of 34.5 mph, the result was protested on the grounds that the car was a factory special, but the protest was dismissed. In motor racing, some things remain the same.

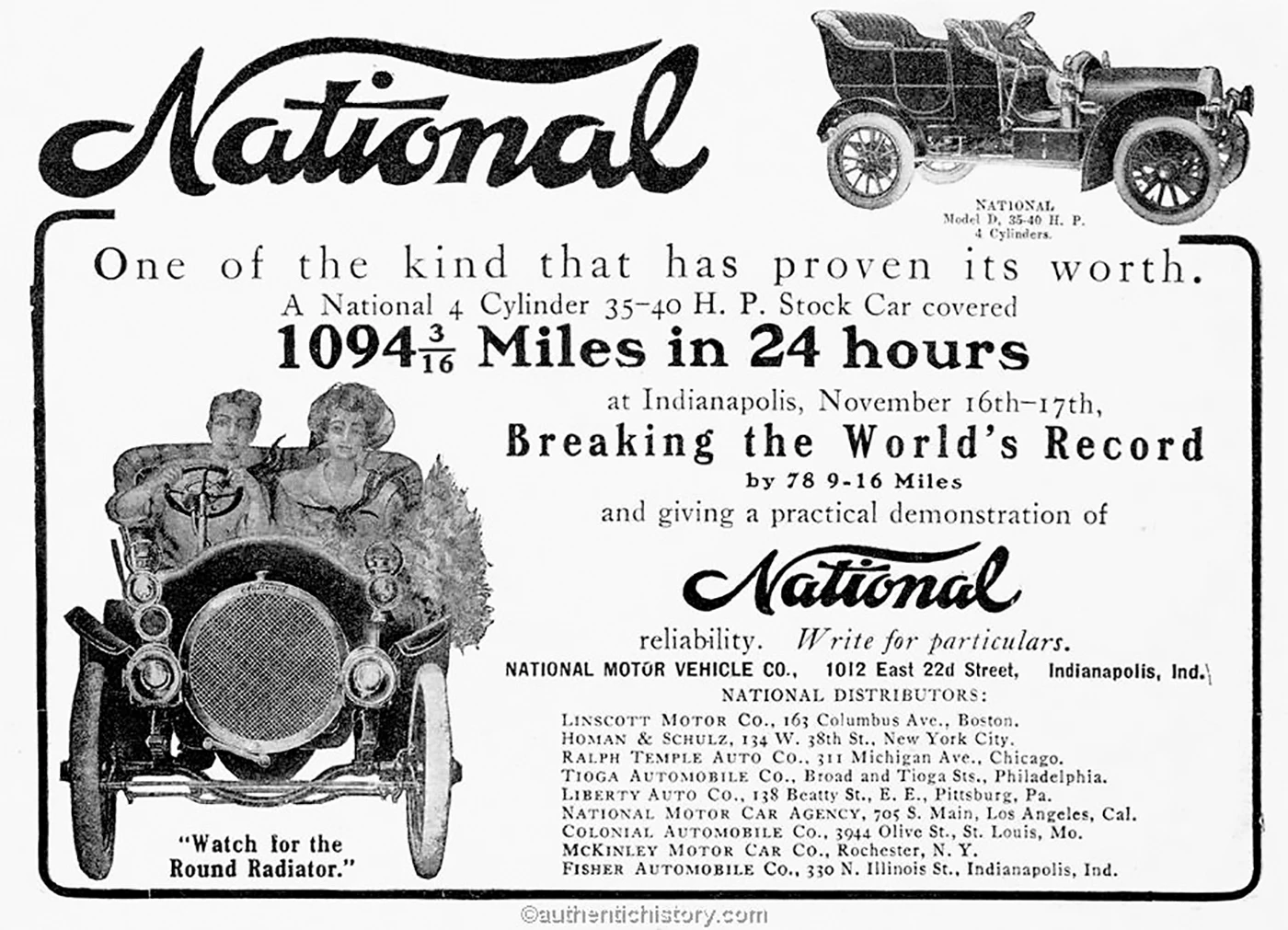

National | 45.6 mph (73.4 km/h)

November 17, 1905 | Indiana State Fairgrounds | Average 24 hour speed

This attempt on the world 24 hour record was organized by the Indianapolis Automobile Racing Association and promoted by Carl Graham Fisher, who would eventually go on to found the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1909, and this event is considered by many to be the conception of "The Brickyard."

Two National Model C cars began the 24 hour, driven by W. F. "Jap" Clemens and Charlie Merz. Clemens crashed when leading by six laps at the 150 mile mark, and was immediately drafted into rotating with Merz. So cold was the weather that the drivers goggles fogged up, meaning they needed to drive without goggles through the night. As the night wore on, driver changes were down to every 30 minutes just before dawn. The time for the 1000 miles was 21:58:00.8 and the new world 24-hour distance record was set at 1,094.56 miles.

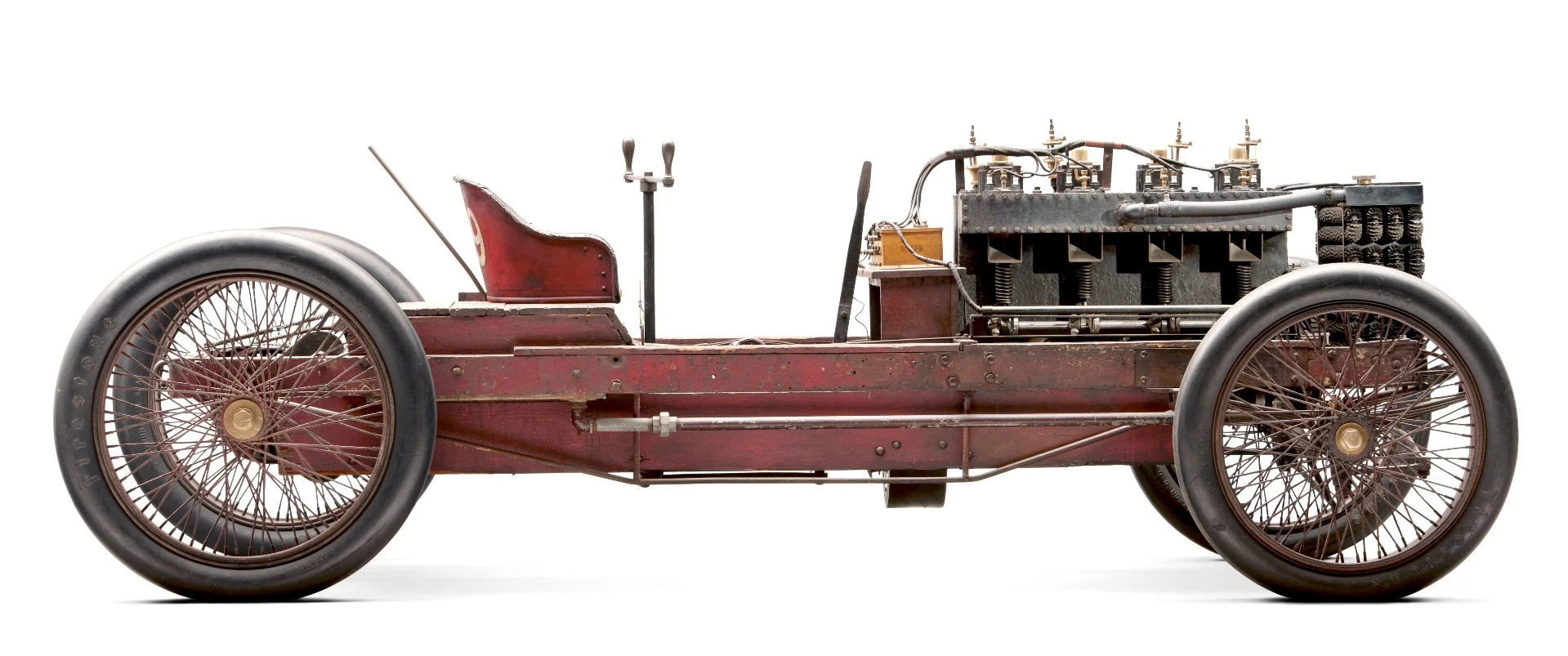

Darracq | 109.7 mph (176.5 km/h)

December 30, 1905 | Arles, France

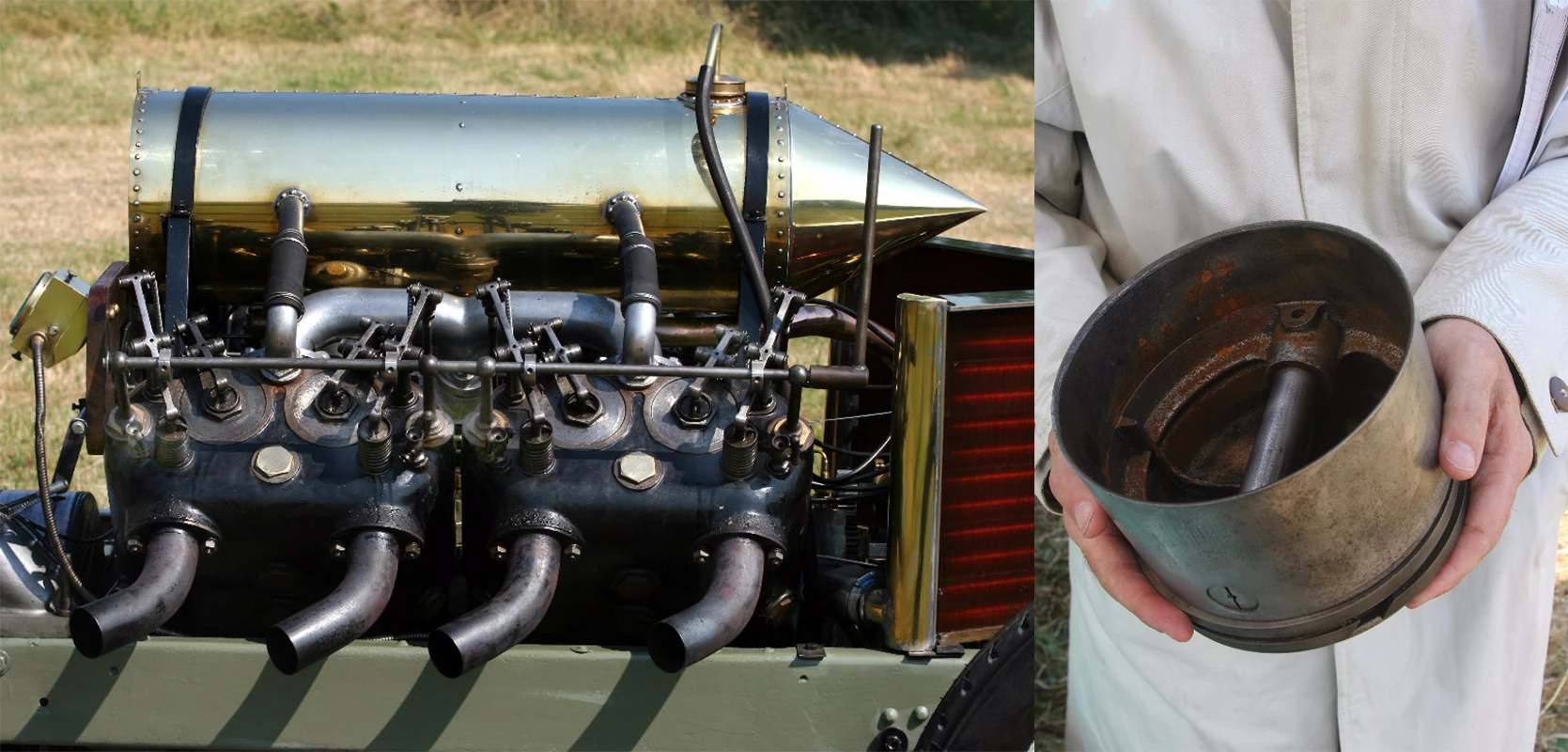

This 1905 one-off Darracq appears to be the very first car built from scratch to contain a V8 engine. And what an engine it was. Four sets of pair-cast cylinders with a swept volume of 25,422 cc producing 200 hp in a car that weighed just 900 kg (1982 lb). Streamlining was for weaklings. This is the epitome of the brute power approach.

Built with one purpose in mind, the car was completed on December 28, 1905 and Darracq was on a mission, so the first attempt was run just two days later.

The car delivered its promise, twice running the same speed of 109.65 mph (176.46 km/h). That's one of the pistons at above right, with diameter of 170 mm and a swept volume of over six liters, which helps frame the perspective of the motor beside it. Two of those pistons were housed in each block.

Veteran professional driver Victor Hemery (winner of the Vanderbilt Cup in 1905) made four runs in all, with three above the existing record. No sooner had the car cooled down than it was shipped to America for the Daytona Beach Speed Trials.

This car still exists, having been found and restored to its former glory. It went to auction with Bonhams in 2006, fetching £199,500 (US$394,700). Bonhams' auction description and hi-res images offer the usual insights and The Old Motor has a splendid article on the car entitled "The Fire-Breathing 1905 Darracq 200 HP Land Speed Record Car."

Pierce Great Arrow

Winner Glidden Tour (1905-1909)

Pierce-Arrow was one of the most prestigious of American manufacturers in this period with the speed to cover vast distances quickly. The company's reputation for performance and reliability was validated when the Pierce Great Arrow won the famed Glidden Tour five years in a row (1905-1909), achieving perfect scores in all but one of them. The name "tour" may not convey the grueling nature of these tours. The following video from King Rose Archives shows the speed and endeavor shown by the drivers in difficult conditions.

The first tour was actually in 1904 (the video is incorrectly labelled) and covered 1350 miles. Though the routes varied with subsequent tours, they were the ultimate test of reliability and speed in America at that time and followed by every newspaper in the land.

Just as speed records were an indication to the public of technological leadership, reliability trials incorporating a range of challenges were also critical in forming brands with longevity and speed as key values.

The car pictured above is a 1905 Pierce Great Arrow 28/32 five-passenger Roi des Belges tourer which would have been indicative of the type of car which won those epic Glidden Tours.

Mercedes 70-hp & Panhard & Levassor 50-hp

1905 | Touring cars capable of traveling at 60 mph in the right conditions

By 1905, the fastest road cars were beginning to diverge slightly from the race cars that were setting speed records, with the Mercedes and Panhard being the ideal cars for those to whom money was no object. They represent the best that had yet been achieved in the building of motor-cars.

The 1905 10.6-liter Panhard & Levassor 50-hp Model Q (above) was designed to compete with the 60 hp Mercedes. The car debuted at the 1905 Olympia Show in London with a price tag of £1750. Against the £2000 of the also-introduced 70-hp Mercedes (below), the 50-hp Panhard was the second most expensive car on the British market. In total, just 79 examples of the Panhard & Levassor 50-hp were built

The Panhard and the Mercedes 70-hp, which eventually began production in 1907, were the cream of the crop for fast luxury touring, more than capable of traveling at 60 mph in the right conditions.

Stanley Steam | 121.6 mph (195.7 km/h)

January 29, 1906 | Daytona Beach, Florida

The potential of steam power was once again demonstrated when it reclaimed the official record at Ormond Beach Florida on 29 January 1906 thanks to the Stanley Steam company.

On 29 January 1906, Fred Marriott drove the Stanley Steam Company's best known creation to set what would be the final record for steam at 127.66 mph (205.44 km/h). The event was reenacted 100 years later with the same car, and this video tells the story.

Unfortunately, real understanding of aerodynamics at speed was still nearly a century away, and the saddest aspect of the Stanley Steam Company triumph of 1906 was the next attempt, which ended when the streamliner flipped at 150 mph in the 1907 Florida meet, ending both Marriot's career and Stanley Steam company's tilt at rewriting history.

Darracq | 122.5 mph (197.14 km/h)

January 29, 1906 | Daytona Beach, Florida | Faster over 2 miles

The Darracq held the speed record coming into the Ormond Beach Florida on January 29, 1906. Sadly, the main driver and developer of the Darracq, Victor Hemery, had a series of disagreements with the organizers and officialdom disqualified him from the meeting.

Hemery's replacement driver was French-American race driver Louis Chevrolet (who would go on to found the Chevrolet Motor Car Company in 1911), but he had no experience driving the car. Chevrolet ran a time of 115.3 mph (185.6 km/h), which meant the Darracq was still the fastest gas-powered car in the world, but the Stanley Steam car obliterated the record on the same day (see above). On the final day of this meeting, the Darracq was matched against the Stanley in a two mile race and Darracq's No 2 driver Victor Demogeot was given the drive instead of Chevrolet.

Marriott's Stanley clocked a time of 59.6 sec with Demogeot timed at 58.8 sec, or 122.5 mph (197.1 km/h). Despite the Darracq being faster over two miles than the Stanley was over one mile, the official record went to the Stanley. A full report on the event can be found in the March 1906 issue of The Automobile Magazine.

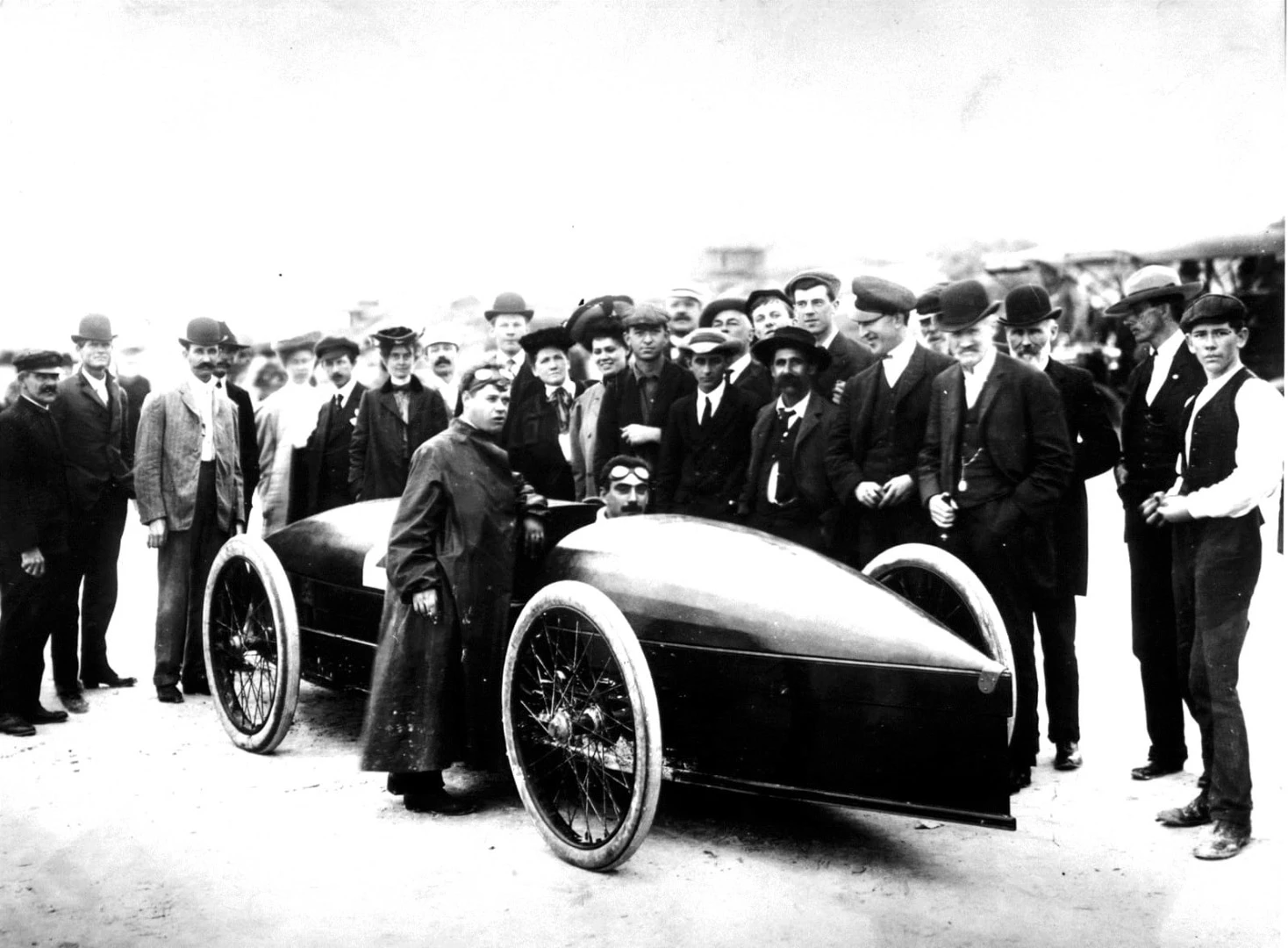

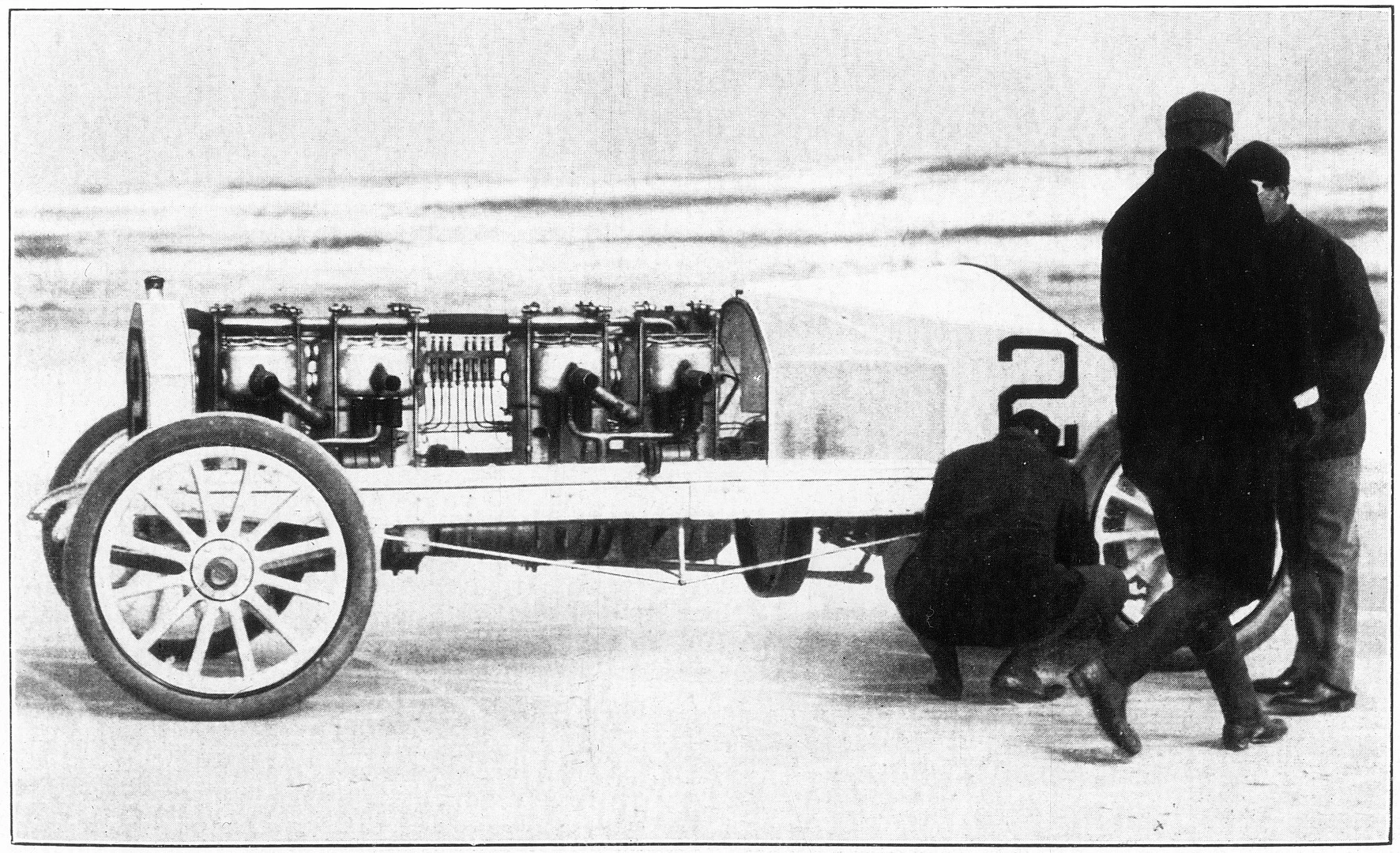

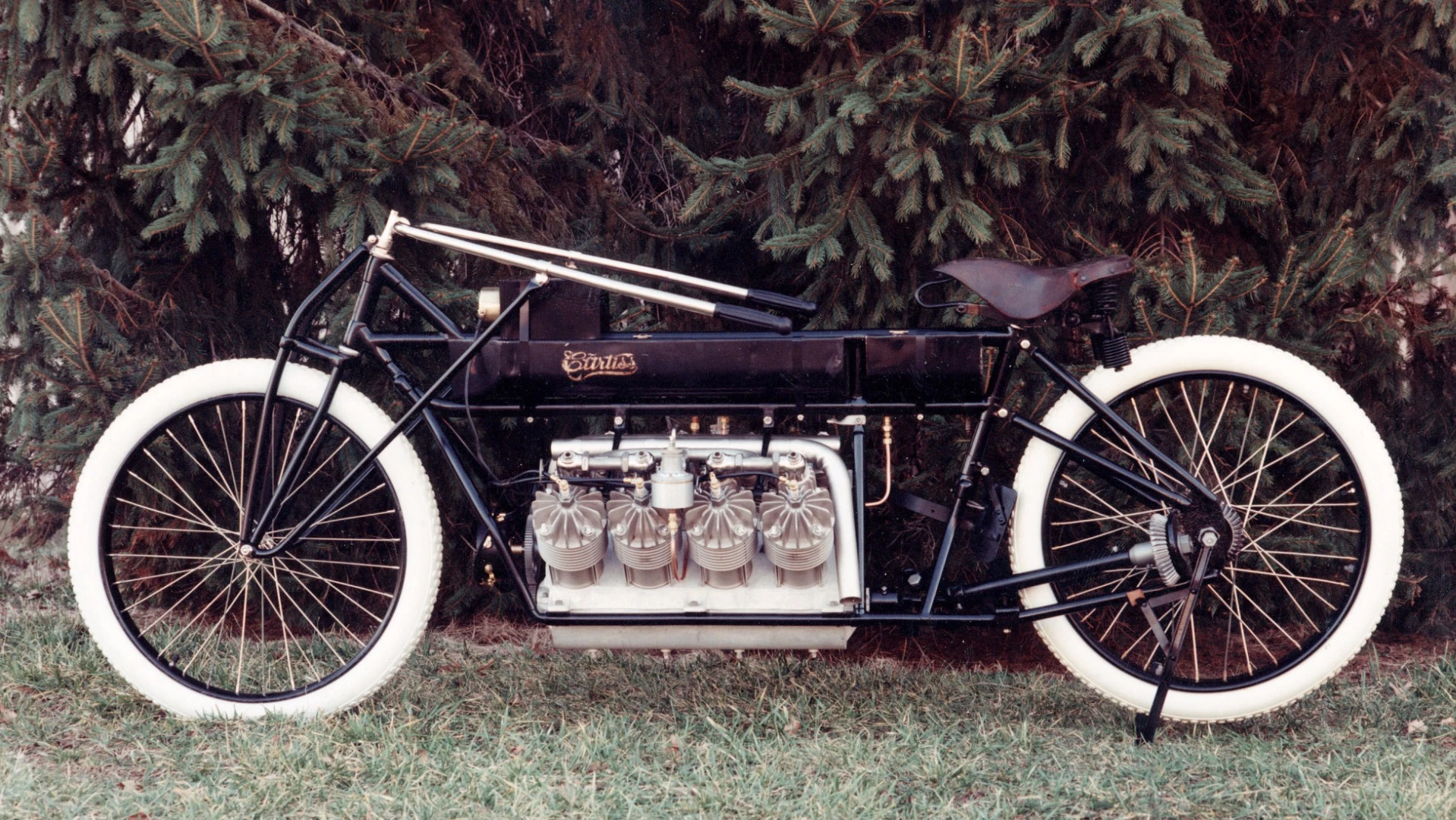

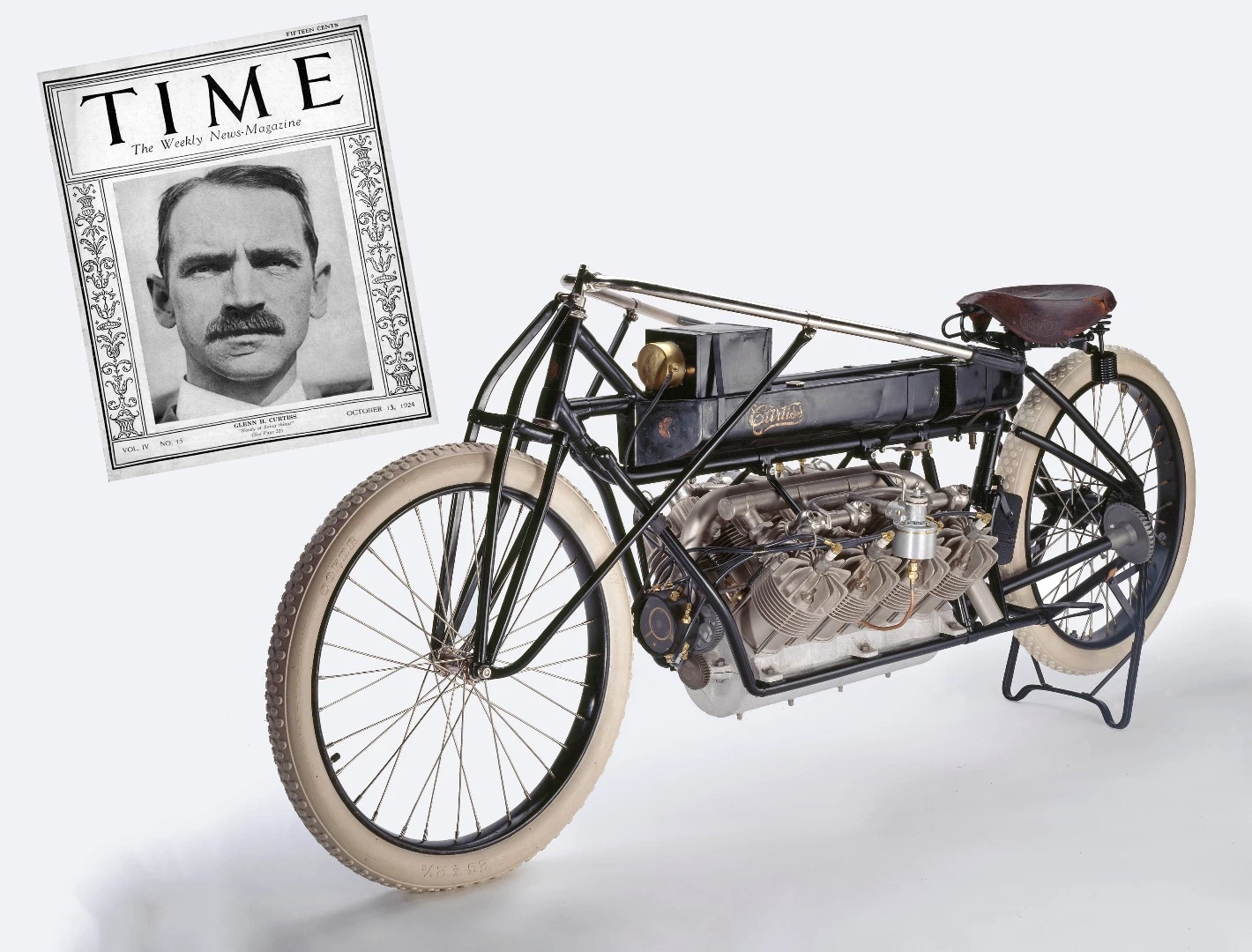

Curtiss V8 Motorcycle| 136.3 mph (219.3 km/h)

January 24, 1907 | Daytona Beach, Florida

Given that the land speed record was held by an electric trolley car at this point in time, and the non-railed land record was held by a steamcar, it seems entirely appropriate that motorcycles should enter the fray, and the perfect person for the introduction was Glen Curtiss, DFC, one of the early civilian recipients prior to it being made a military-only award.

Curtiss was one of the great aviation pioneers and is generally regarded as the father of naval aviation through his subsequent work with sea planes. Prior to the aviation business he manufactured engines and motorcycles and one of his earliest motorcycles, the Curtiss Hercules 1000 cc v-twin recorded 64 mph (103 km/h) at Yonkers in New York on May 30, 1903 and earned him a place in history as the first motorcycle speed record holder.

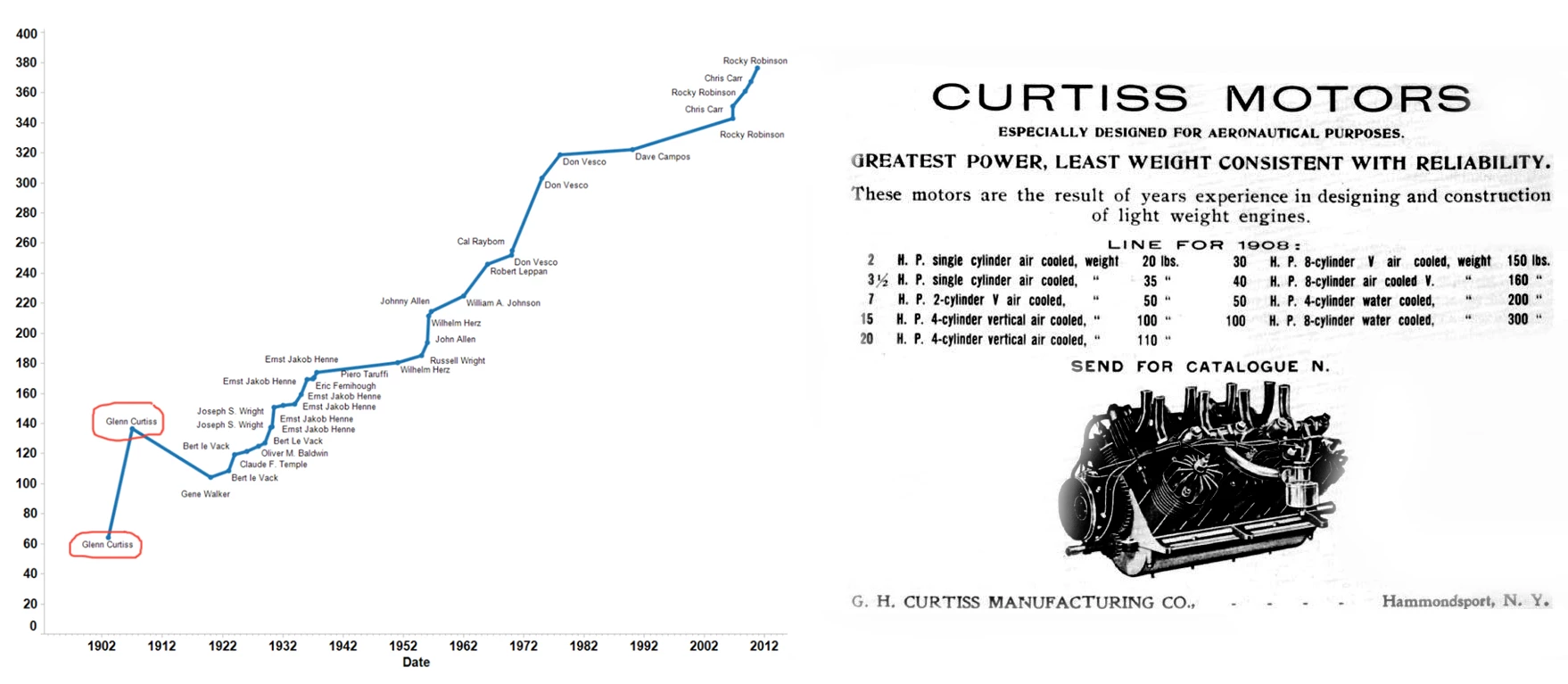

Curtiss' main business was the manufacture of high-power, lightweight engines for a range of purposes. As an aviator, he was so significant he made the cover of Time magazine. He was a contemporary of the Wright Brothers and as a brilliant engineer, he realized the low weight and minimal frontal area of the motorcycle offered an easy way to demonstrate his wares to the public and sell more of his engines, so he installed one of his 4000cc V8 aircraft engines (essentially four of his v-twins), into a motorcycle and blew all competitors into the weeds with a run of 136.27 mph (219.31 km/h) on January 24, 1907. Those are the first two data points on the graph (above left), showing the progress of the motorcycle speed record from 1906 onwards. You can see Curtiss was decades ahead of his time.

Glen Curtiss designed and built not just the only motorcycle to have held the land speed record, but if you count the aforementioned electric trolly record in 1903, and all the prior speed records held by trains, the land speed record had been held by public transportation systems (trains and trolleys) until Curtiss rode the first road vehicle with tires to claim the outright record land speed record. The Curtiss 4.0 liter V8 motorcycle was both the first non-railed vehicle to hold the land speed record and the first internal combustion engined vehicle to do so.

The Curtis V8 that held the unofficial world record until 1930 is resident in the Smithsonian, and an exact replica has been created for the Curtiss Museum.

Napier | 65.9 mph (106.1 km/h)

June 28-29, 1907 | Brooklands, United Kingdom | 24 hour average speed

On 17 June 1907, the famous banked high speed racing circuit at Brooklands opened and on 28 June 1907, Selwyn Edge used the new venue to set a new 24-hour distance record.

Edge's effort was well coordinated, with the track marked out by 352 lanterns and further illuminated by huge flares, and the car fitted with large driving lights. With the help of some nifty pit stop work, he was able to coax his 60 hp Napier six to cover 1,581 miles (2544 km), 1,310 yards in the 24 hour period at an average speed of 65.905 mph (106.06 km/h). Such was the advantage of the banked Brooklands track that the Napier's 24 hour distance record would stand until the fourth running of the Le Mans 24 hour race in 1926. Edge also pushed the one hour distance record to 70.07 miles in same attempt.

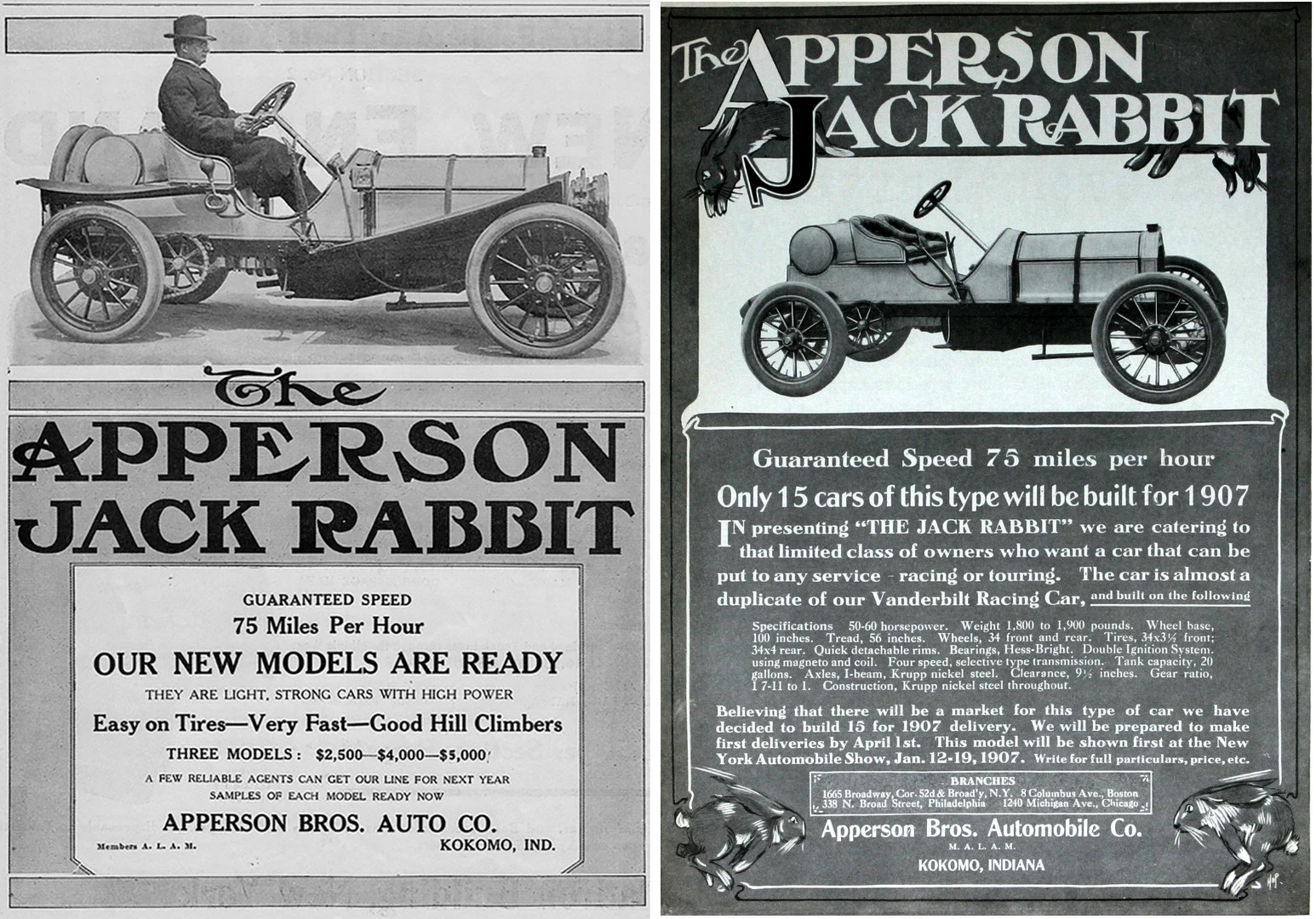

Apperson Jack Rabbit | Guaranteed 75 mph (120.7 km/h)

1907 | Guaranteed top speed

There can be little doubt from looking at the advertisements above from 1907 that the American Apperson Jack Rabbit was a sportscar in every sense, with a guaranteed top speed of 75 mph (121 km/h) and the advertisement reading: "In presenting 'The Jack Rabbit' we are catering to that limited class of owners who want a car that can be put to any service – racing or touring."

The Jack Rabbit was a two-seat roadster with a 96-hp, four-cylinder engine with 4-speed transmission and was performing well in the inaugural 1910 Indianapolis 500 when a freak accident (the car was in the pits when another car crashed into it) took it out of the race, but not before it had been timed at 91.83 mph (147.78 km/h).

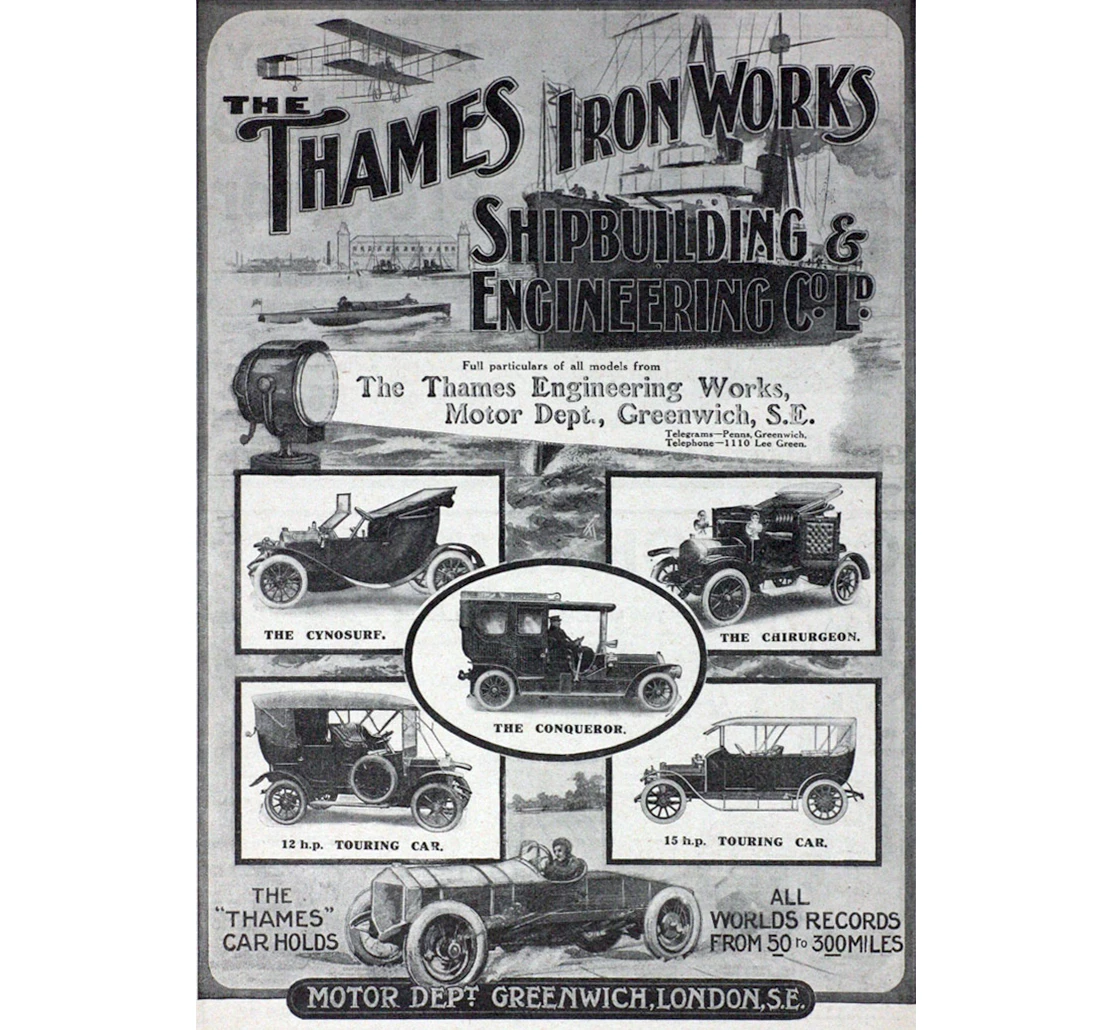

Thames | 76.26 mph (122.7 km/h)

December 10, 1907 | Brooklands | One hour average speed

Edge would have gone into 1908 with every major automotive speed record if it had not been for a late attempt by W. T. Clifford Earp on December 10, 1907 at Brooklands. Edge's six-cylinder 60-hp Thames set a new record for an hour (76.26 miles) along with records for 50 miles (76.58 mph) and 150 miles (75.95 mph) and two hours(75.95 mph).

Napier 60 hp | 85.3 mph (137.3 km/h)

February 19, 1908 | Frank Newton's new one hour average

Frank Newton was by now Napier's lead driver and on February 19, 1908, Newton used a 60-hp Napier at Brooklands to take the 50-mile, 100-mile, 150-mile, one hour and two hour records. In the hour Newton covered 85 miles, 555 yards.

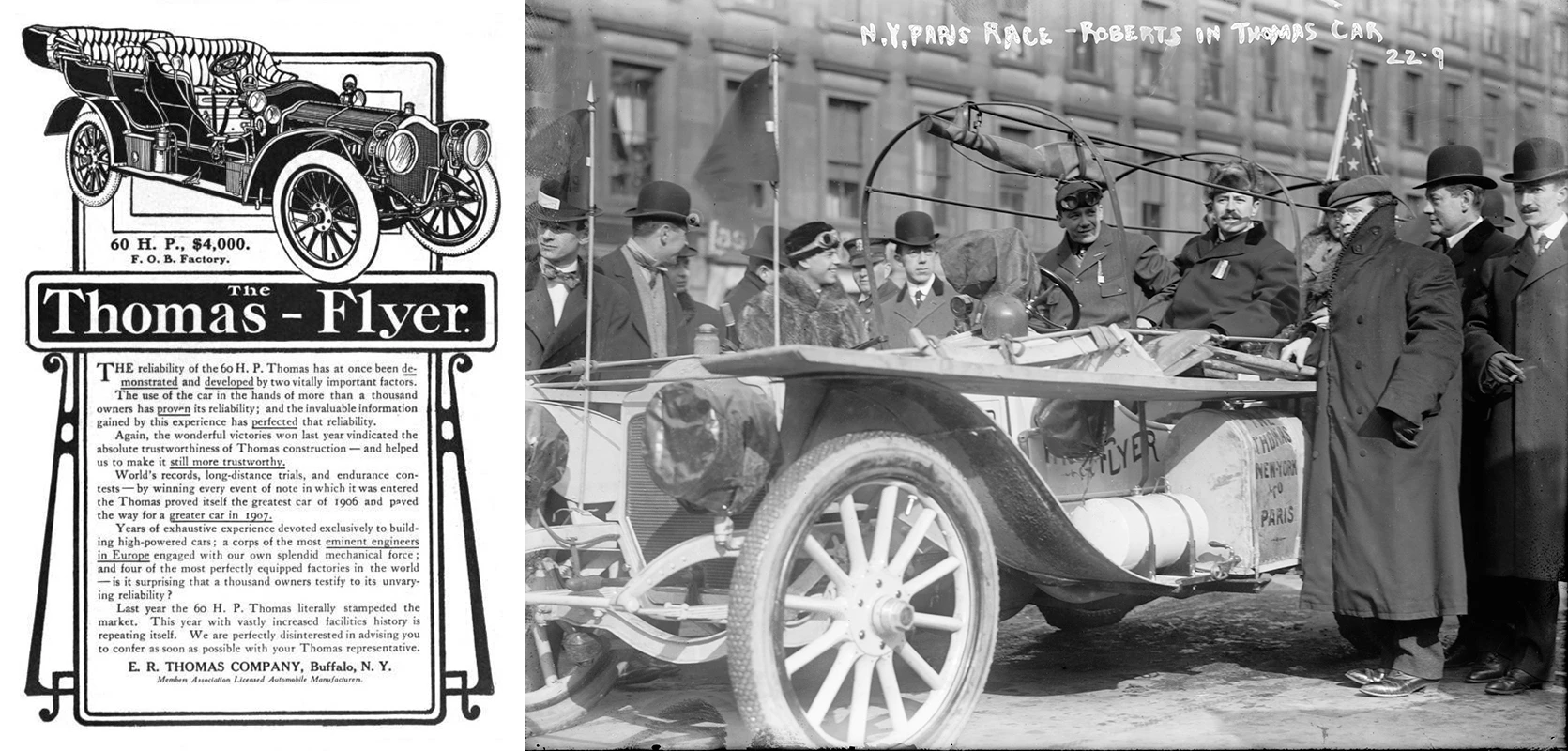

Thomas Flyer 60 hp

1908 | Winner New York to Paris automobile race

This is the car that won the famous New York to Paris automobile race in 1908 - it's an off-the-shelf 1907 Thomas Flyer 4-60 model and in winning the epic race, it enhanced an already sound reputation for speed and reliability to legendary status. Even if motorcars aren't your schtick and you don't know what it did, you will have heard of the "Thomas Flyer" even though the last one was made 97 years ago. The pioneering company achieved many great feats with its wares, but winning the only around-the-world race that's ever been held is the marque's greatest achievement.

The race from New York to Paris commenced in Times Square (New York) on 12 February 1908 and the winning Thomas arrived in Paris on 30 July 1908, having covered 16,700 km (10,377 mi) in 169 days. The race was front-page news around the world, both before, during and after the six month affair, and the world lived the great adventure vicariously through the newspapers.

The winning Thomas Flyer was a production car in every respect. "It shows the American car is on par with the foreign machine, and it marks the beginning of the end of the European supremacy," claimed Robert Lee Morell at the Auto Club of America at a luncheon upon the car's arrival in the US.

The above 1908 Thomas Flyer Model F 4-60hp Tourer went to auction at Bonhams Quail Lodge sale during 2010 Monterey car week and fetched US$ 733,000. The winning car from 1908 is on display in Reno, Nevada, at the National Automobile Museum, alongside the trophy.

Benz Prinz Heinrich Wagen | Approx. 80 mph (130 km/h)

Argued by some to be the world's first sportscar, first produced in 1908

While the best known Prinz Heinrich "race replicas" were produced by Austro-Daimler and Vauxhall in 1911, the Benz Prinz Heinrich Wagen was a replica of the car that won the inaugural 1908 event and was available in 1908, three years ahead of the 1910 Prinz Heinrich Fahrt replicas from Vauxhall and Austro-Daimler. It was available as a production vehicle across four model years from 1908 to 1911 and was listed in the Mercedes catalog, albeit on special request, so it predates either the Vauxhall or Austro-Daimler as the world's first race replica and hence sportscar.

The inaugural 1908 Prinz Heinrich Fahrt was won by a Benz driven and designed by another important motorsport figure – Fritz Erle. Erle was already the head of the racing department for Benz, also driving the cars in major races with plenty of success, and he would lead the development of the 200-km/h (124 mph) Blitzen Benz of 1909 that eventually captured all race and speed records until 1919. Initially a run of 100 cars was planned for production, but around 50 were built before WWI got underway.

Thames | 89.5 mph (144.1 km/h)

November 5, 1909 | Brooklands, United Kingdom

Record attempts were so plentiful in this period that it's difficult to keep track of them all. C.M. Smith took a host of World records on 5 November, 1909 in a 6-cylinder Thamescar. He claimed the one-hour record at 89.51 mph (144.1 km/h) and in a second attempt on the same day averaged 91.32 mph over 50 miles.

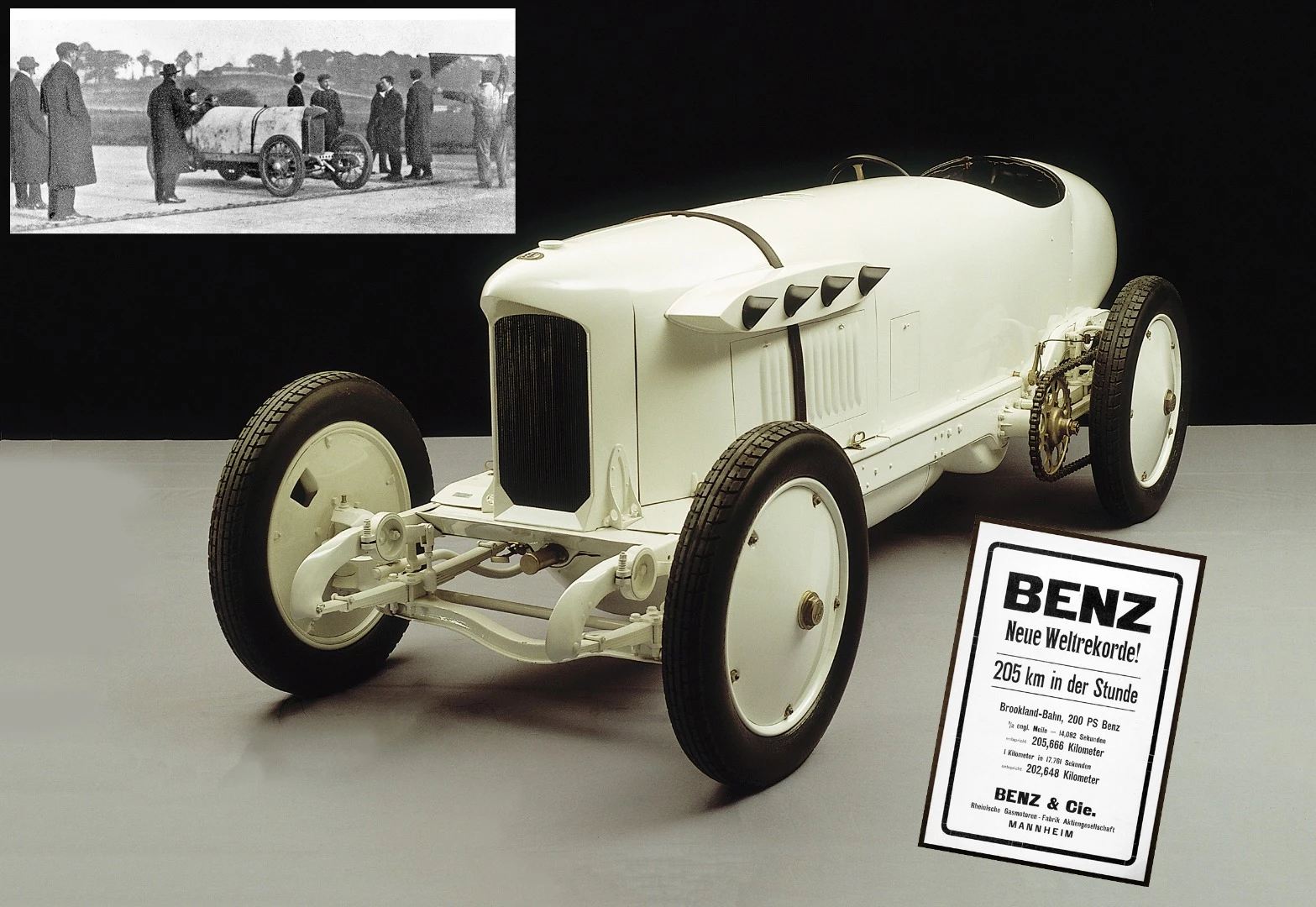

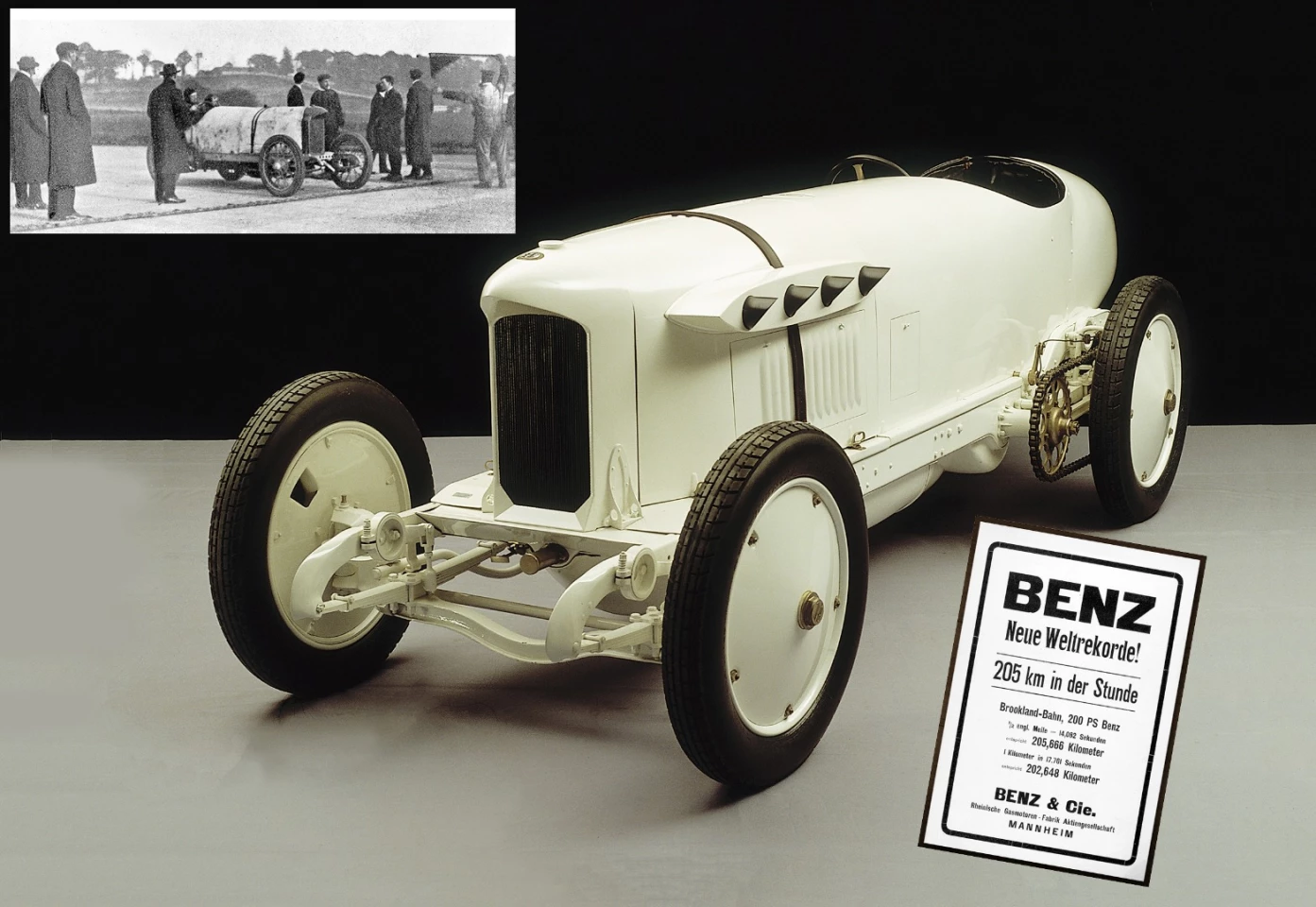

"Blitzen" Benz | 125.9 mph (202.6 km/h)

November 8, 1909 | Brooklands, United Kingdom

The Blitzen-Benz was built specifically by Benz & Cie (which would join with DMG to create Mercedes-Benz in 1926) to establish new speed records and at its heart was a 21.5-liter four-cylinder engine producing 197 hp. Victor Hémery, now a driver and manager for the Benz team, took the Blitzen Benz to Brooklands racetrack in England on 8 November 1909 and ran 205.666 km/h (127.795 mph) for the flying half-mile and 202.648 km/h (125.919 mph) for the flying kilometer, with the speed electronically timed to 1000th of a second for the first time.

It hence became the first car to break the 200 km/h (124 mph) mark and was to become dominant in the pre-WWI period.

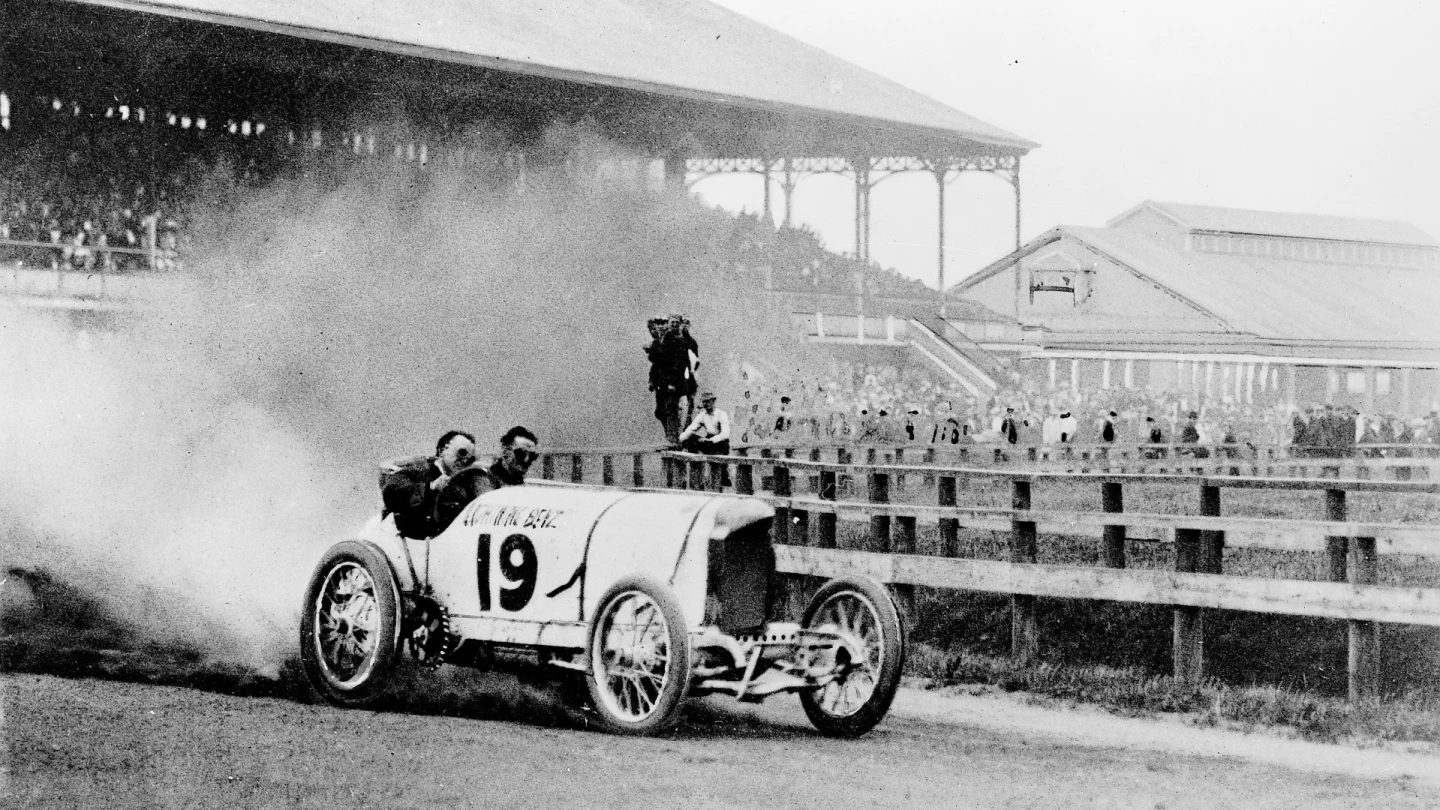

"Blitzen" Benz | 131.3 mph (211.4 km/h)

March 17, 1910 | Daytona Beach, Florida

On 17 March 1910, Barney Oldfield (who had driven Henry Ford's 999 car to a 91.37 mph record in January 1904) set a new speed record of 131 mph (211 km/h) at Daytona Beach, Florida, driving the 200 hp Benz. Sadly, it would not be recognized, though Oldfield was certainly a first-hand witness to the phenomenal speed increases as his records were just six years apart.

Benz & Cie knew that achieving success with the record-breaking car in the important North American market would be good for business. The car was given a new body and shipped to America in January 1910, but when Benz importer Jesse Froehlich took delivery of the car, race promoter Ernie Moross offered his 150-hp Grand Prix Benz plus US$6000 dollars in exchange for it, Froehlich accepted and Moross began a publicity tour-de-force in which Oldfield won almost every race he entered, with Moross pocketing the lion's share of the "Lightning Benz" or "Blitzen Benz" appearance money which was reportedly $5000 minimum.

Oldfield entertained spectators all over America with his antics in the remarkable car, and the hysteria was further fueled on March 17, 1910 when Oldfield lined up at Daytona Beach with just the normal preparation and ran a mile at 131.36 mph (211.4 km/h). The A.I.A.C.R. (Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus - a precursor to the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile that governs motorsport) did not recognize the record because the Benz had not run in both directions. Moross didn't care, because the newspapers were trumpeting the record anyway.

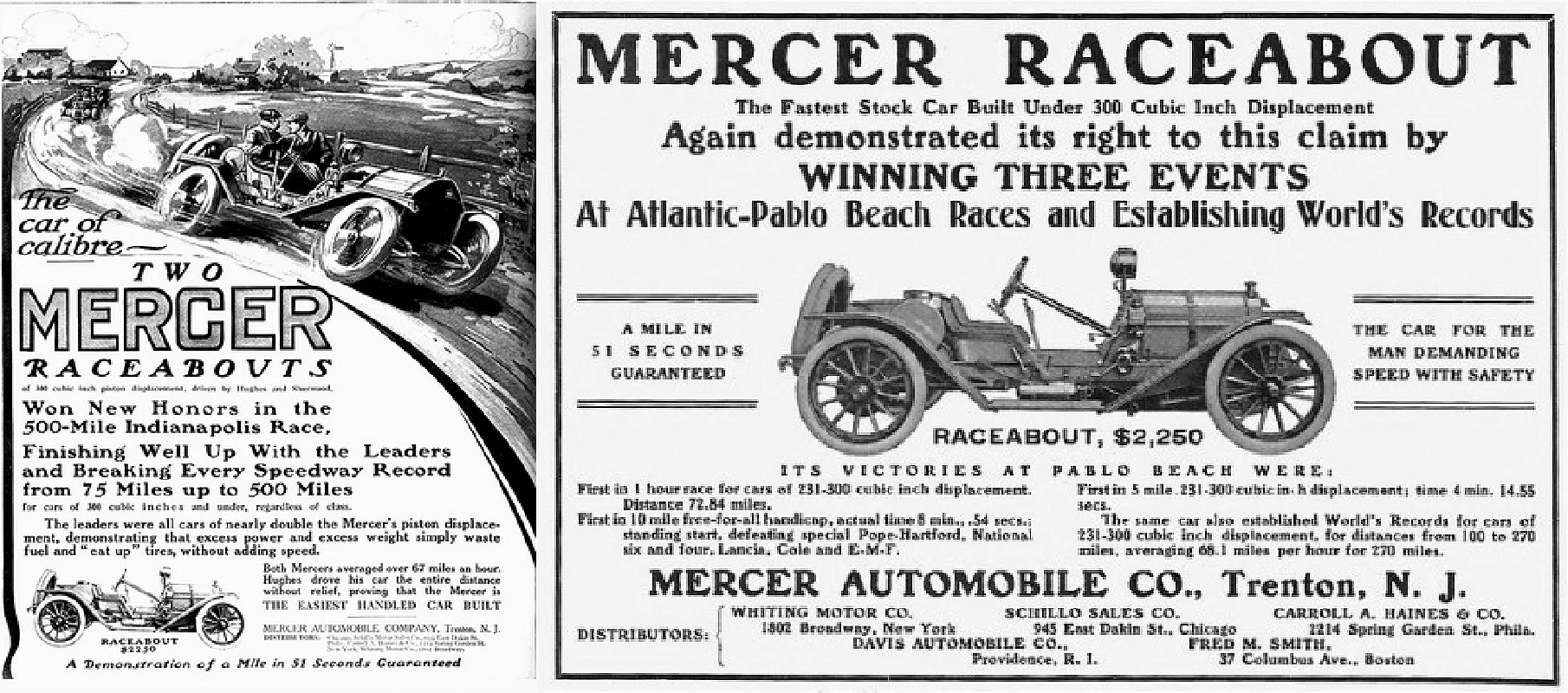

Mercer Type 35R Raceabout | 90 mph (145 km/h)

1910 | United States

The American Mercer 35R Raceabout was a sportscar sold between 1910 and 1914, with a string of major victories in American racing from 1911 onwards. The 35R Raceabout sold for US$2,250 at that time, the price of a modest home. It was not only very expensive, but a genuine production sportscar with a powerful 300 cubic inch T-head four-cylinder engine producing 58 hp at 1,900 rpm. The Raceabout's 4,800 cc, 4-cylinder Raceabout won five of the six 1911 races it was entered in, losing only the first Indianapolis 500. Many racing victories followed and the Raceabout became one of the premier racing thoroughbreds of the era.

RMSotheby's sold a 1911 Mercer Type 35R Raceabout for $2,530,000 at Monterey in 2014, producing the above video to promote the sale, which gives a real feel for what the car was like. Hemmings estimates there are between 30 and 35 T-head Mercer Raceabouts extant, validating the production status of the Raceabout, which was unquestionably a sportscar.

Hispano-Suiza Alfonso XIII | 75 mph (120 km/h)

Often acclaimed as the world's first sportscar

Hispano-Suiza (literally, Spanish-Swiss) was founded in Barcelona in 1904, its name recognizing the nationality of its brilliant partner and engineer Marc Birkigt. Spain's young King Alfonso XIII was one of Hispano's first customers. When Hispano-Suiza's new racing voiturette (less than 750 kg) car won France's prestigious Coupe de l'Auto race in 1910, it was turned it into a road car and Alfonso drove the new model, bought one and gave permission for the new model to carry his name. The endorsement of royalty was reserved for wares of the finest quality, and with the royal imprimatur, a factory was built in Paris in 1911 to target the far greater potential of the monied and much larger French market, which enjoyed the best roads in the world at that time.

The auction catalogue description for the car pictured above reads: Lightweight, narrow and with a centrally positioned engine, the Alfonso XIII can be considered the archetypal sports car. In 1911 the four-cylinder engine was enlarged from 2.6 to 3.6 litres, gaining a four-bearing crankshaft in the process, and in 1913 a four-speed gearbox adopted. The maximum power output of 64bhp was delivered at a lowly 2,300rpm, and with a top speed of around 120km/h (75mph), the Alfonso XIII was one of the fastest road vehicles of its day. Progress was arrested by means of a handbrake operating two drums on the rear axle, and a foot-operated transmission brake. Production continued until 1918 by which time around 600 Alfonsos had been built, only about 25 of which are known to have survived.

Benz | 141.4 mph (227.5 km/h)

April 23, 1911 | Daytona Beach, Florida

Bob Burman broke Barney Oldfield's record, covering a mile from a flying start at an average speed of 141.37 mph (228.1 km/h) in the Blitzen-Benz at Daytona Beach, Florida on April 23, 1911. This was the highest speed ever attained by a road vehicle prior to WW1 and set up a world record that remained unbeaten until 1919.

Over the flying kilometer, the car reached an equallyimpressive 226.7 km/h and the original car has now been restored and featured at a number of major Concours events, including the 2011 Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance.

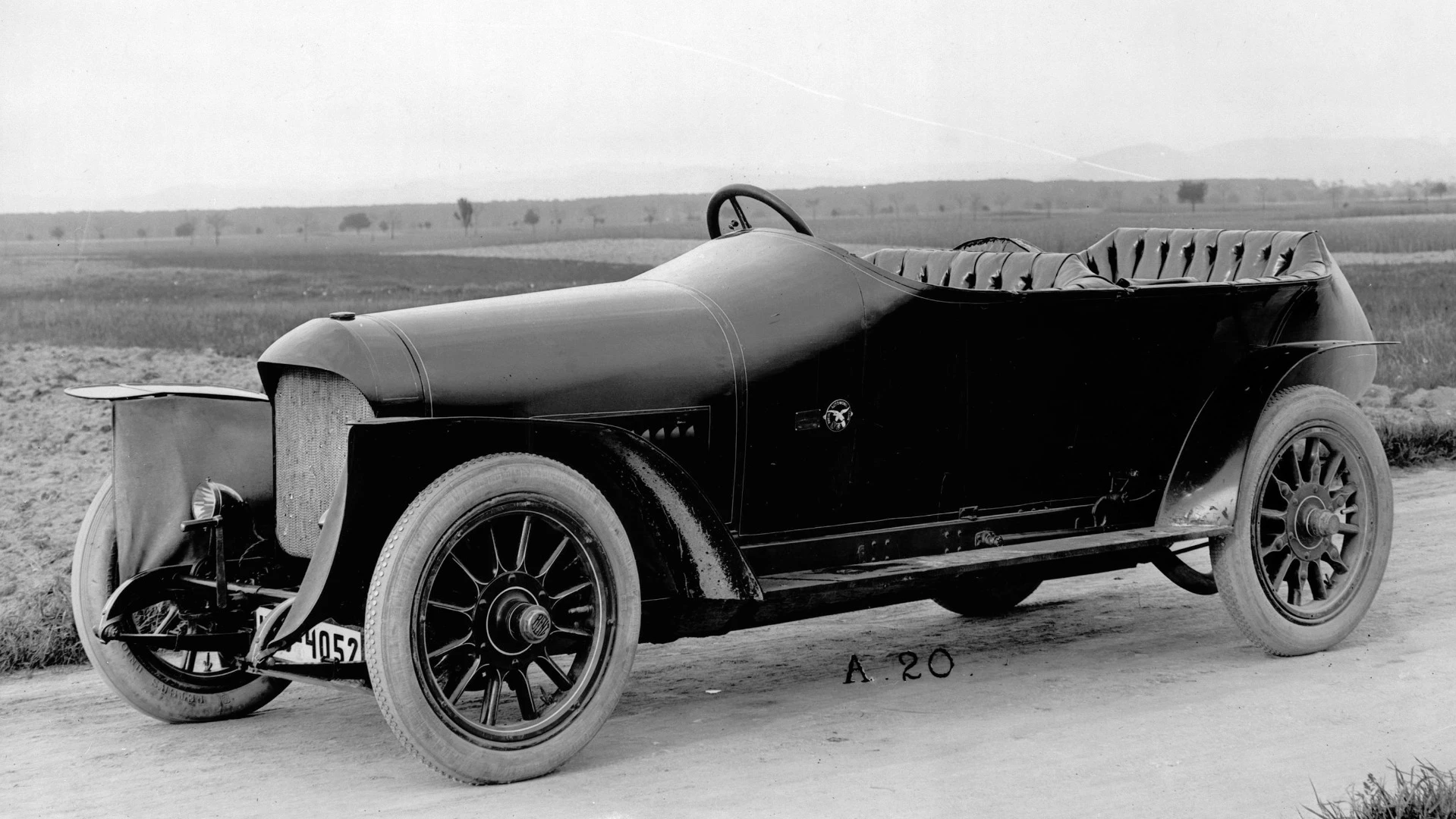

Austro-Daimler Prinz Heinrich | 85 mph (136.8 km/h)

1910 | Clean sweep of German Alpine "Prinz Heinrich Trial"

This car is often referred to as the world's first sports car. It was built by Austro-Daimler, an Austrian subsidiary of the German DMG (Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft) that merged with Benz to become Mercedes-Benz 15 years later.

The car was designed by Ferdinand Porsche and made a 1-2-3 clean sweep of the 1910 German Alpine "Prinz Heinrich Trial." The trial was named after the auto enthusiast younger brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, and was a contest for four-seat passenger cars. Ferdinand Porsche actually drove the winning car in the trial (above), and the model was named after the trial, just as many replica cars after it were named in honor of a glorious victory for their respective marques.

With its 95 hp 5.7 liter engine, the Austro-Daimler Prinz Heinrich would have been one of the fastest road cars at this time. Initially a run of 100 cars was planned for production, but only around 50 were built before WWI got underway.

The Austro-Daimler Prinz Heinrich is another car in the mix when to topic of the world's first sportscar is discussed.

Vauxhall C10 Prince Henry

1911 | Swedish Winter Trial in 1912

The Vauxhall Prince Henry was named after three 20-hp A-type Vauxhall cars that competed in the 1910 Prinz Heinrich Fahrt, with the British Vauxhall company anglicizing the name for its primary public.

The epic 1910 event covered 1,495 km (927 miles) from Berlin to Bad Homburg (near Frankfurt) and was both grueling and had timed sections based on outright speed, so it was unquestionably a sporting contest.

Vauxhall sent a factory team driving Vauxhalls, which successfully completed the challenging 1910 tour and Vauxhall launched the new 20-hp C-Type model in 1911, adopting the v- shaped radiator and fluted bonnet as used by the factory cars in the Prinz Heinrich Fahrt.

The "Prince Henry," as the C-type became known, was initially offered in 20-hp guise, then increased in engine capacity to the four-liter 25-hp model in 1912. The Vauxhall Prince Henry went on sale in 1911 for £485 (excluding the body) and its reliability and speed won countless trials, races and hillclimbs in the next few years, including the Swedish Winter Trial in 1912.

Despite its four seats, the Vauxhall Prince Henry is often considered as another contender for the title of world's first sportscar.

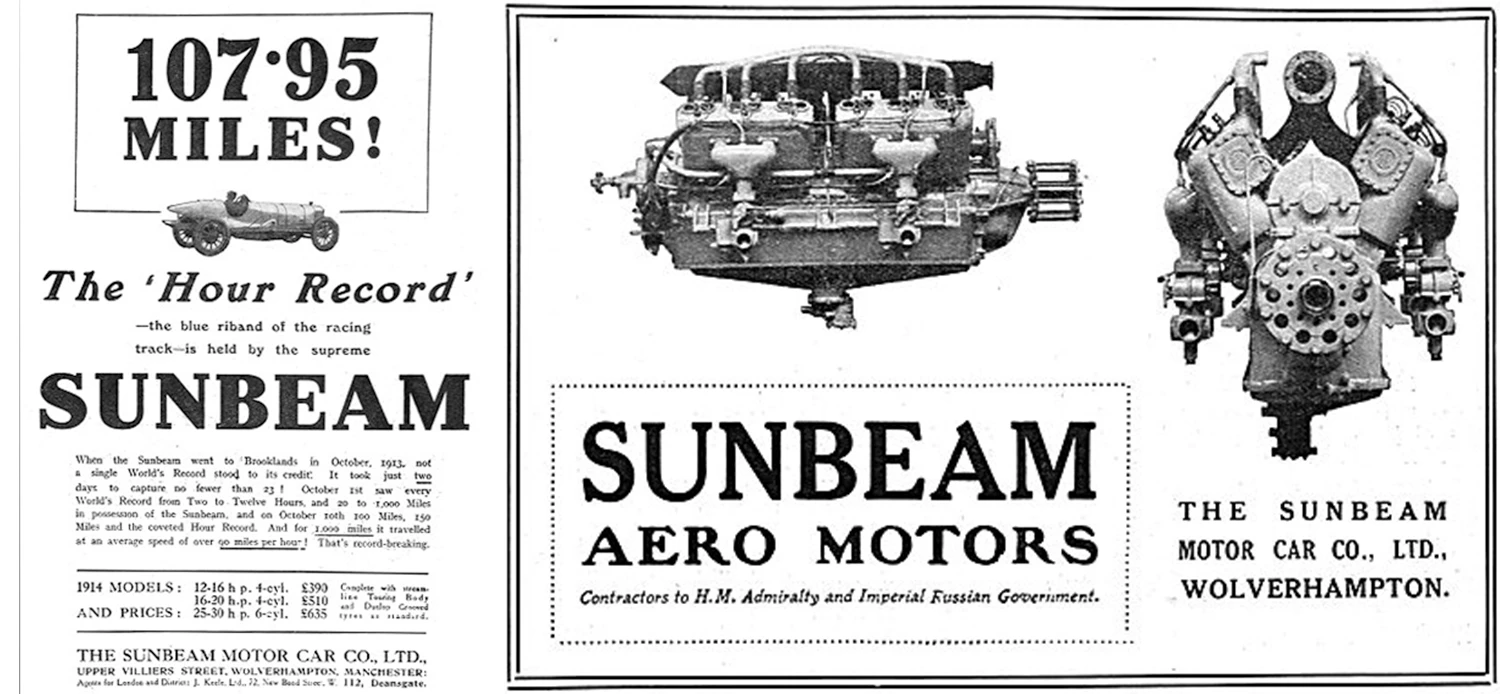

Sunbeam | 92.45 mph (148.8 km/h)

October 11, 1912 | Dario Resta takes world one hour distance record

The Sunbeam "Coupe de L'Auto Replica" was a limited production road car that was sold by Sunbeam in 1913/14. It is the only production road car in history that was simultaneously successful in Grand Prix racing and the holder of multiple land speed records.

It was a replica of the Sunbeam 3.0 liter "Voiturette" (think F3) which competed in the French Grand Prix and Coupe de l'Auto of 1912, achieving a spectacular result against state-of-the-art open class Grand Prix cars.

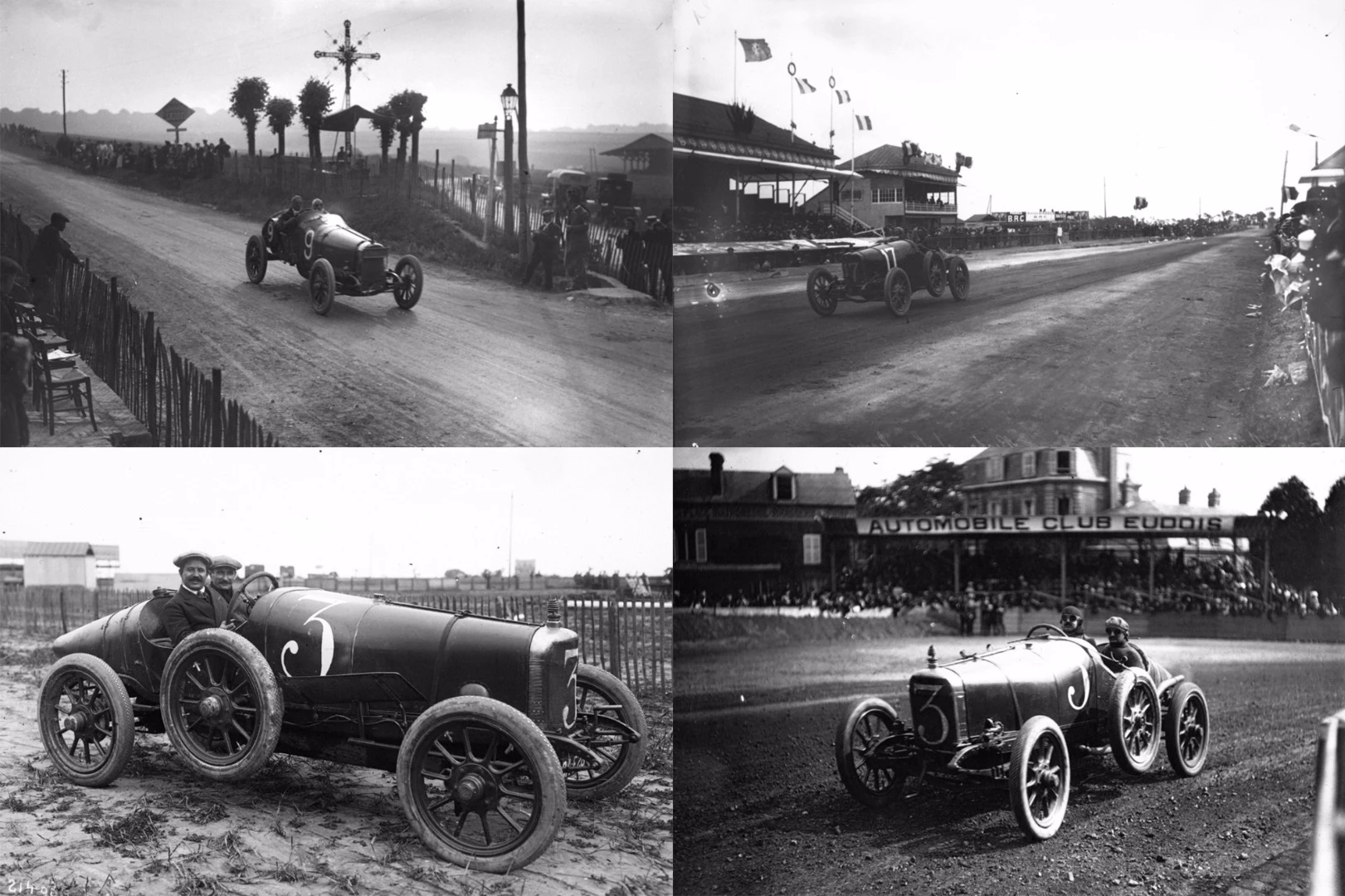

The Coup de l'Auto was the major race in Europe for 3.0 liter Voiturette racing cars at that time and over two days in June 1912 the race was run simultaneously with the 1912 French Grand Prix in Dieppe. A massive field comprising 15 different makes of car started at one minute intervals, completing ten laps of the 47.8 mile (77 km) course each day with aggregate time over both days deciding the result.

In the Voiturette class, the 3.0-litre Sunbeams took the win with Victor Rigal behind the wheel, but with Dario Resta second, Emile Medinger third and Joseph Christiaens fourth, all in identical cars, Sunbeam had a 1-2-3-4 result.

In the Grand Prix class there was a high attrition rate with only 15 of 48 starters finishing the grueling 957 mile (1540 km) distance and the lightweight, sweet handling and very quick Sunbeams placed 3-4-5-6 in the open class, scoring a podium position in the French Grand Prix, the most important race in the world at the time. The Sunbeam was beaten only by the new 7.6-liter DOHC 4-valve Peugeot Lion of French superstar Georges Boillot and the 14-liter Fiat S74 of Louis Wagner.

One of the cars which raced in Dieppe was taken to Brooklands several times with all three drivers present and it captured a swathe of records, with Resta taking the one hour distance record with 92.45 miles covered.

The company publicity focussed heavily on its Dieppe result, and the Sunbeam Coupe de L'Auto Replica was put on sale for the bargain pice of £425 in 1913. At that time, a Rolls-Royce cost £1500, so it wasn't even frightfully expensive. Imagine what a roadgoing F1 car that could also break the world speed record would sell for today?

1912 | Lorraine -Dietrich | 97.59 mph (157.06 km/h)

November 27, 1912 | Average speed over 100 miles

On November 27, 1912, Victor Hemery took one of the four 15-liter Lorraine-Dietrich Grand Prix cars built for the French Grand Prix in June to Brooklands, establishing a raft of records. Now known as Vieux Charles III, this car is still going strong as this story from the Brooklands Museum explains. Hemery set every record feasible but missed narrowly on becoming the first person to cover 100 miles in an hour, coming in at 97.59 miles.

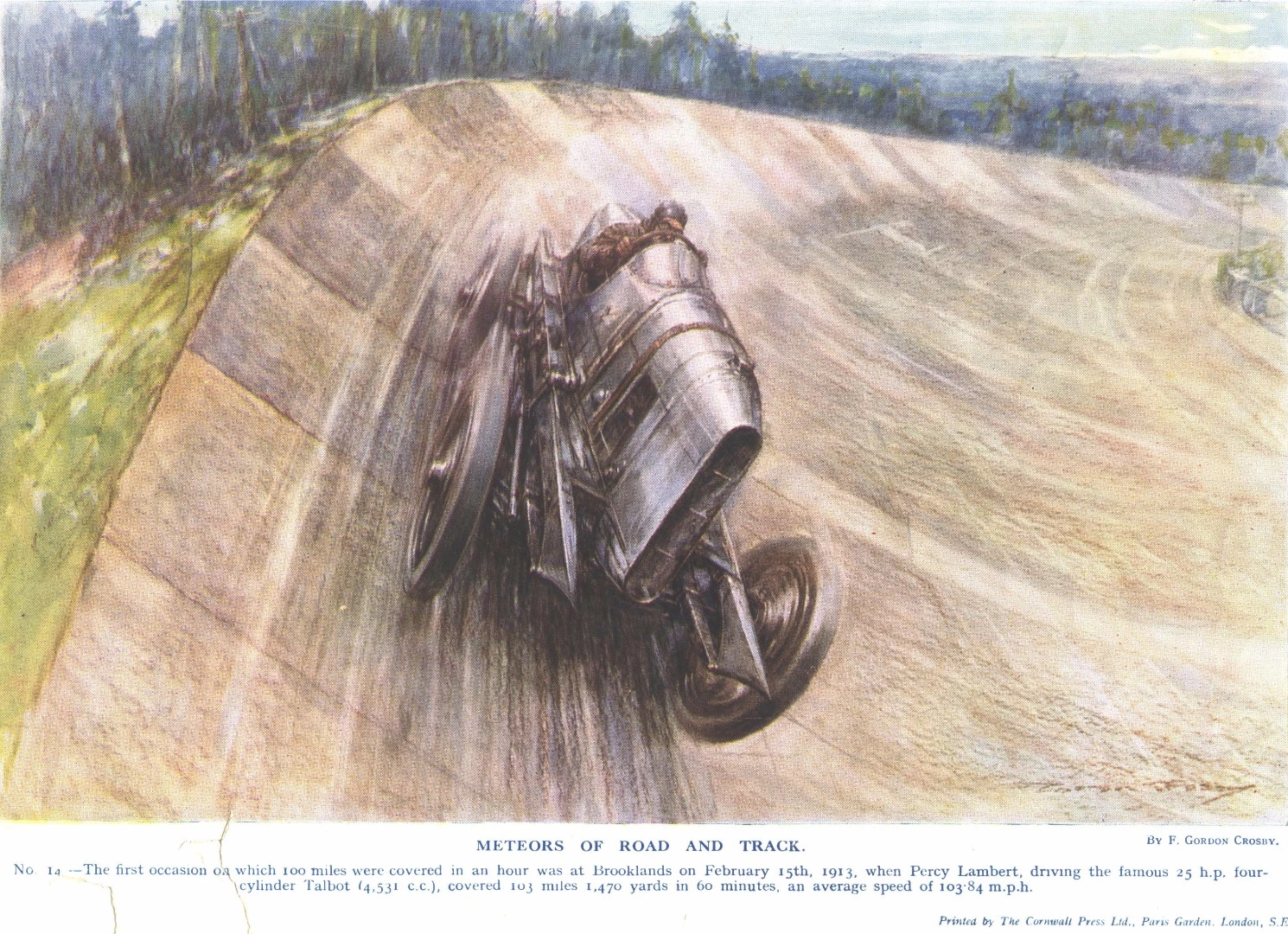

1913 | Talbot | 103.84 mph (167.11 km)

February 15, 1913 | 100 miles in one hour for the first time

There's a big difference between reaching a velocity of 100 mph and actually covering 100 miles in an hour. The first person to achieve that was Percy Lambert on February 15, 1913 driving a 4.5 liter sidevalve Talbot reportedly producing 105 bhp at 2,500 rpm. He actually covered 103 miles and 1470 yards (167.34 km) in sixty minutes.

After the initial standing lap at 87.24 mph, Lambert consistently lapped above 100 mph, his quickest lap at 106.42 mph. The result was 103.84 miles covered in the 60 minutes, the first time any car had exceeded 100 miles in the hour. Lambert would be killed later that year attempting to break his own record.

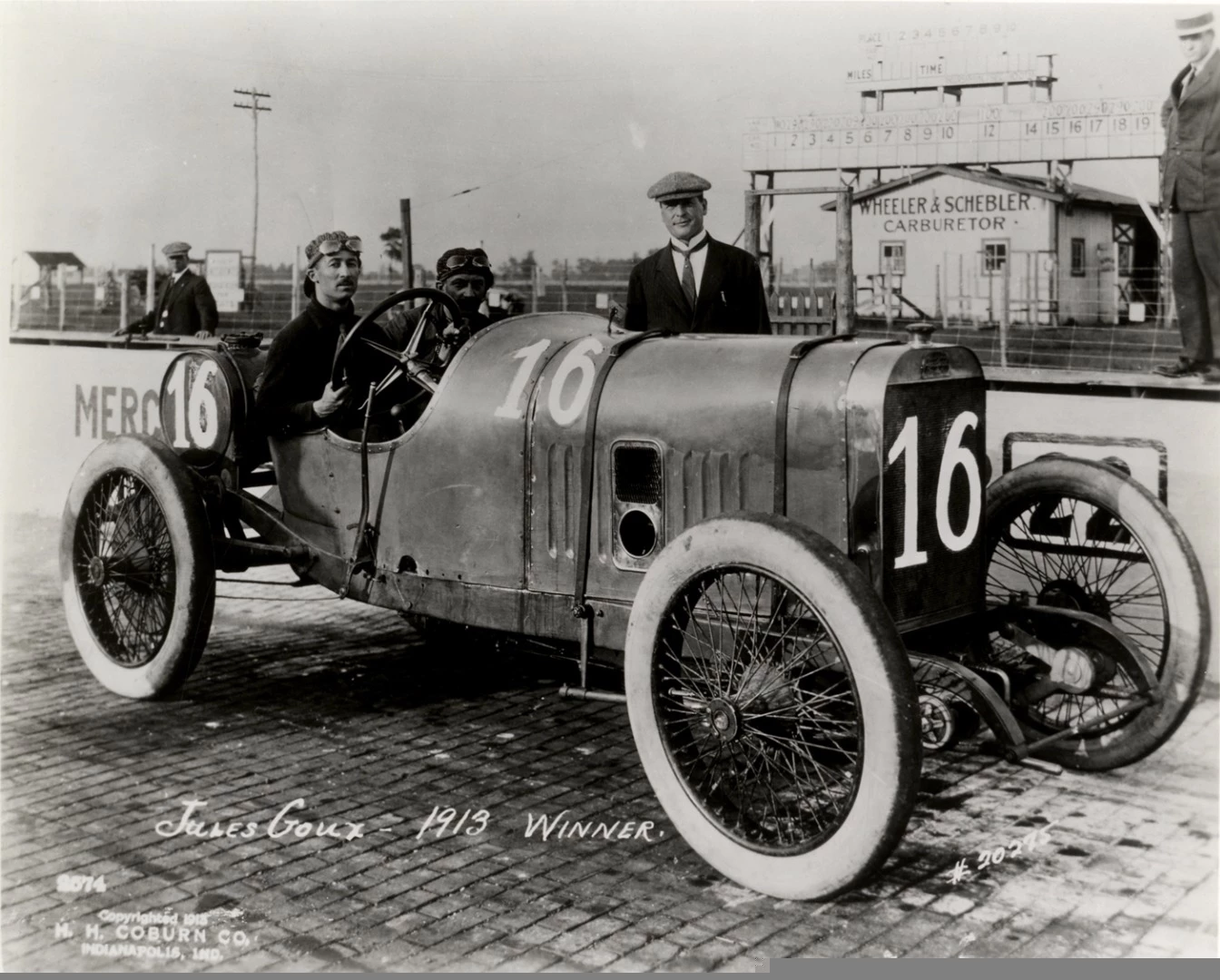

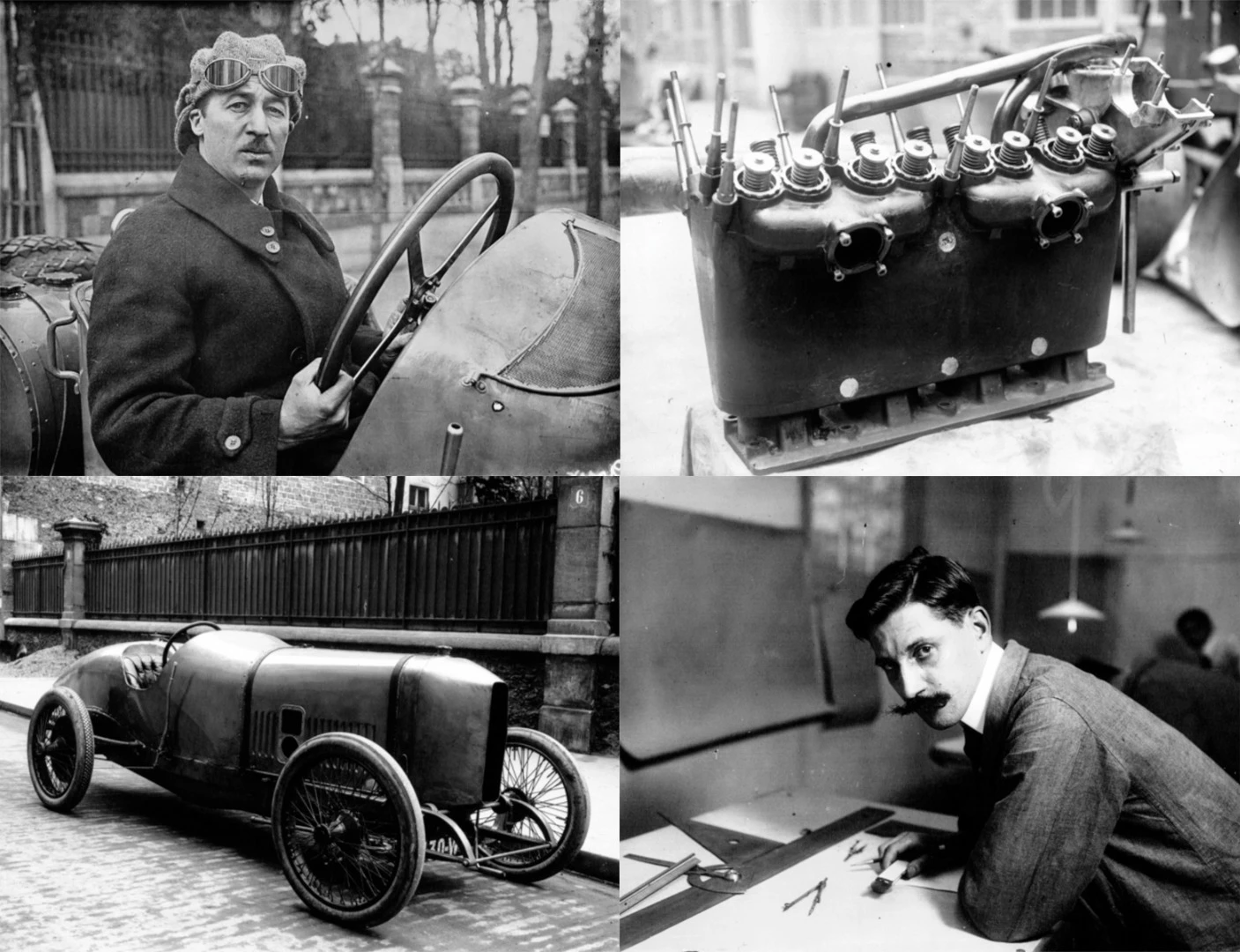

1913 | Peugeot | 106.2 mph (170.9 km/h)

April 12, 1913 | One hour distance record broken at Brooklands

Jules Goux was part of the four-man team which revolutionized automobile engine design with the Peugeot Grand Prix racer of 1912. The team, led by Ernest Henry (below bottom right), produced a DOHC, four-valve-per-cylinder, 7.6-liter, four-cylinder engine which first competed in the 1912 French Grand Prix, winning in the hands of Georges Boillot. This was the very first car with a DOHC 4-valve motor (below top right) and a special streamlined version of the next 4.5 liter DOHC Grand Prix car named "La Torpille" (above) was prepared for Goux (below top left) to use in a record attempt at Brooklands.

Goux broke Lambert's one hour distance record by covering 106.2 miles in an hour, taking the 50 mile record (105.97 mph), 100 mile record (106.2 mph) and 150 mile record (105.9 mph).

The Peugeot's 4-valve DOHC 4-cylinder engine design would become standard fare for sportscars over the next century, and beginning with the 1912 Grand Prix win, Peugeot used its technological advantage to great effect, taking the 1913 French Grand Prix and 1913 Indianapolis 500 at an average of 75.92 mph, timing on the straight at 93.5 mph.

Following revelations that Goux drank champagne during the pit stops of his Indianapolis win, a new rule was implemented banning consumption of alcohol by competitors.

In 1914 at Indianapolis, Boillot's 3-liter L5 Peugeot went close to the first 100 mph lap (99.5 mph (160.1 km/h) at Indianapolis, but the engine expired (with Peugeot running first and third) and Duray drove the best-placed Peugeot into second. Another second place in 1915 and a win in 1916 indicate that the Peugeot was equal to the fastest grand prix cars of the period.

Sunbeam | 107.95 mph (173.7 km/h)

October 9, 1913 | One hour record claimed by first V12 car engine

Engine technology was progressing at an ever-increasing rate thanks to the additional R&D being applied to aero engines and their need for ever greater and reliable power in the fast growing, 10-year-old aerospace industry.

On October 1, 1913, the Sunbeam single-seater, 4.5-liter, 6-cylinder car averaged 90 mph for 1000 miles at Brooklands, taking a raft of records as it was expertly driven by the accomplished team of Jean Chassagne, Keiran Lee Guinness (heir to the brewing dynasty and subsequently founder of KLG sparkplugs) and Dario Resta.

On 4 October, 1913, Sunbeam's brilliant engineer Louis Coatalen rolled out the car that everyone knew was in the wings, the first car to use a V12 engine. In essence, it was two of the six cylinder engines mated on an aluminum crankcase for a displacement of 9.0 liters and an output of 200 bhp (150 kW) at 2,400 rpm. Like the six cylinder engine, the internals of the V12 were developed from Sunbeam's aero engines, with the banks of six cylinders set at 60 degrees for theoretically-correct engine harmonics.

On its first competitive outing at Brooklands on 4 October, the car showed more potential with each race, lapping at 118.58 mph (190.83 km/h) during the meeting, the fastest ever lap of Brooklands to that time (not counting the Nazzaro's 121.64 mph lap of 1908, which is commonly believed to be a time-keeper mistake).

On October 9, Coataeln returned to Brooklands with his three star drivers and the V12 with record breaking in mind. Jean Chassagne was the driver chosen to attack the one hour distance record. His first lap from a standing start averaged 95.118 mph, then laps at 117.46 mph and 114.40 mph followed before he settled into a rhythm and lapped consistently at just above 107 mph. The 50-mile record fell at an average 108.88 mph (175.23 km/h), 100 miles at 107.95 mph (173.73 km/h).

By the end of 1913, Sunbeams held every world speed record from 50 miles to 1,000 miles and from one hour to 12 hours. Coatalen went on to become one of the leading designers of engines for British aircraft in WWI, alongside W.O. Bentley and Sir Henry Royce, and between the wars he would design the engines for the first cars to exceed both 150 mph and 200 mph.

"Blitzen" Benz | 124.09 mph (199.70 km/h)

June 24, 1914 | Brooklands, United Kingdom | First two-way run

This was the first record set under new rules that required two-way runs for speed attempts and was yet another record for the 200-hp Blitzen Benz. Set on June 24, 1914 at Brooklands in the United Kingdom, the Blitzen Benz was driven by Lydston Hornsted. Within months, the great war consumed Europe and every available technology was repurposed. By comparison to the insanity of war, going round and round in ever faster circuits seemed entirely rational.

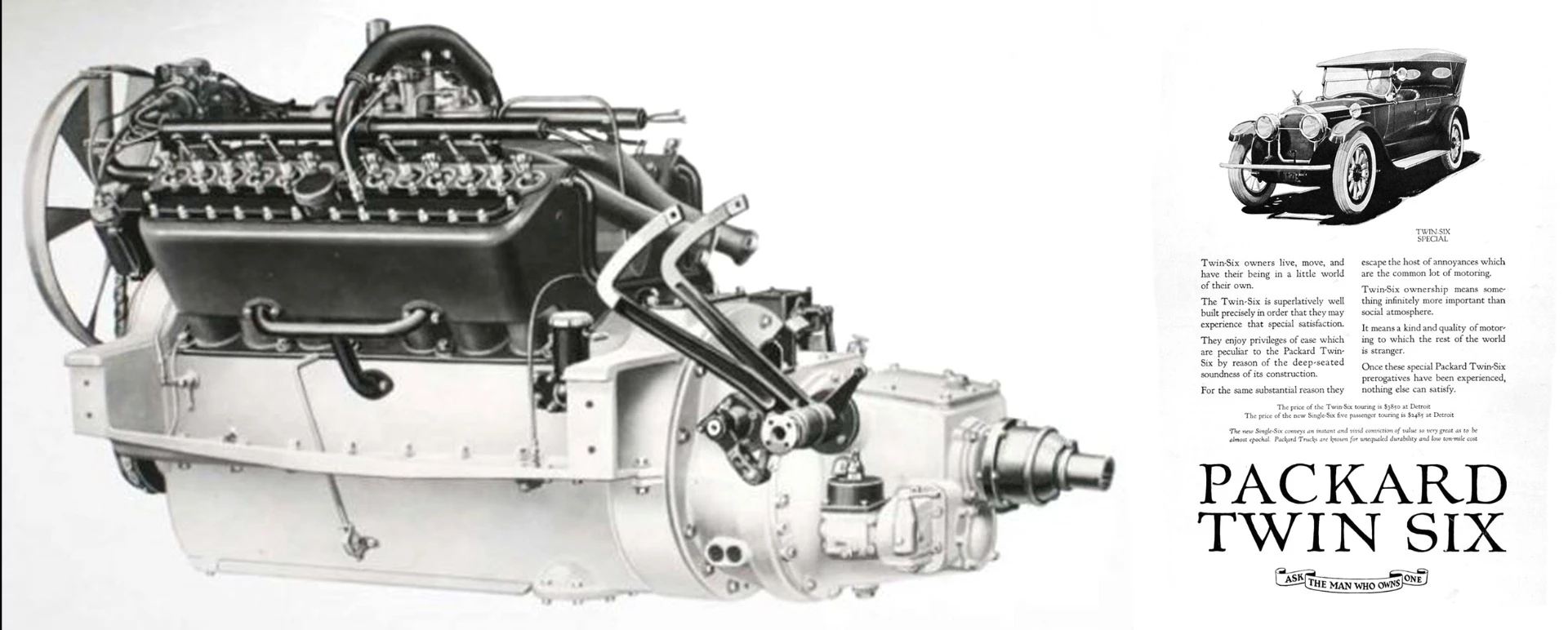

1915 | Packard Twin Six | 72.7 mph (117.1 km/h)

The first V12 road car

The upper echelon of luxury automobile producers in America as WWI began was a contest between Packard and Cadillac. In 1915 Cadillac introduced a V8 production car and Packard introduced the first V12 production car, completing an extraordinary journey from one to 12 cylinders in just 20 years.

Packard's V12 engine used a 60 degree cylinder angle, side valves and 6.821 liter displacement (76.2 mm × 127 mm) to produce 88 hp at 2,600 rpm. Power was delivered through a multi-disc clutch and a manual three-speed gearbox. It was the model which really made Packard's name for smooth, endless power delivery and Enzo Ferrari was a big fan of this engine.

The Packard Twin Six was something of a lumbering beast, but in July 1915, race car driver Ralph De Palma coaxed the car to an average speed of 72.7 mph (117.1 km/h) on a lap of the Chicago Speedway.

The Packard Twin Six model ran until 1923 with few changes and the main image is of a 1918 Packard 3-35 Twin Six Custom Ormonde Roadster sold by Bonhams at Amelia Island in 2016.

Thanks for reading this far and if you have any suggestions for data points or vehicles we've missed in this contentious but fascinating area of automotive history, please feel free to alert us via the comments.

Stay tuned for the final part of our history of the world's fastest road cars. In the meantime check out our first installment covering the fastest production cars of the modern era.