Chevrolet has put some work into its little Bolt electric car, and is aiming for a big payoff as a result. To showcase this effort, the automaker asked us to drive it along America's Northwestern coast.

When the Bolt launched in 2016, it had about 238 miles (383 km) of range per charge. Its price tag was under US$40,000 (before incentives) and its design promised “normal” hatchback looks. After the initial blast of its unveil and the short stint of promotion afterwards, however, the Bolt kind of sat on the sidelines. As a result, sales never really jumped forward.

When Chevrolet offered to let us drive the updated 2020 Bolt EV, we took the chance with some skepticism. How great could this car be if General Motors seemed to have forgotten about it?

It turns out, Chevy didn’t forget about the Bolt, it just concentrated advertising in key markets and worked to steadily improve the car’s underpinnings. The Bolt has thus gotten more range, more safety tech, a couple of new colors, and will soon get a lot more marketing as Chevy ramps up the message for its little EV.

To start with, the primary concern with any battery electric vehicle is range, and the Bolt EV – while having plenty – was still not appealing to a broader market due to range concerns. What GM learned is that consumers need education about range estimation, and what that means. So a series of outreach programs has begun. Meanwhile, the battery techs at Chevrolet tweaked the Bolt’s cells to eke more range out of them without adding weight or size to the batteries.

The result of that tweaking was a 21-mile (34-km) increase in range for the 2020 model, boosting it to 259 miles (417 km) of range per charge (per EPA estimates). These changes came largely due to layer modifications in the cells themselves (all 288 of them), which Chevrolet best explains using a layered cake analogy. As layer thicknesses are modified, so is range and capability. For the cells in the Bolt to get the most bang for the buck without compromising longevity and mass requirements, the changes had to be subtle. Engineers think they’ve found the perfect balance of frosting and cake for the Bolt’s wafer cells ... not that we were going to take their word for it without testing the hypothesis a little.

Our drive started in downtown Seattle at a brewery, where actual layer cake was being given out. It was important to eat that cake, because we were researching battery tech. Clearly.

Early the next morning, we proceeded to head towards the coast. A few things are key to how this played out. The car was fully charged and had already been acclimatized while plugged in. Everything was checked and set up through the MyChevrolet app, which wirelessly connects a smartphone to the car and allows a lot of useful things to be done remotely to the Bolt EV (whether it’s plugged in or not). These include things like interior temps, exterior temp checks, charge state, current vehicle status, door locks, and seat heating.

Once in the car and driving, our attention was mostly keyed towards the city’s traffic, but after getting out of town and on the highway, we were able to refocus towards the car itself and our use of it. Since the weather outside was nice enough, there was no reason to run climate inside, saving us a lot of charge. Similarly, we made use of the “one pedal driving” feature, which is allowed through the Low setting on the gearshift. It can also be activated in one-off use via a paddle on the back side of the steering wheel.

Those familiar with the Toyota Prius’ “B” mode and the Nissan Leaf’s “One Pedal” system will understand how this works. The idea is to use the motor as an engine brake to slow the vehicle, while avoiding touching the physical brakes. This converts the kinetic energy of the vehicle into power for the batteries. Nearly all electrified vehicles have regeneration capability, the one pedal setup just takes it to the next level for more aggressive regeneration. We quickly learned that it can be modulated in the Bolt by feathering the throttle to decrease the aggressiveness.

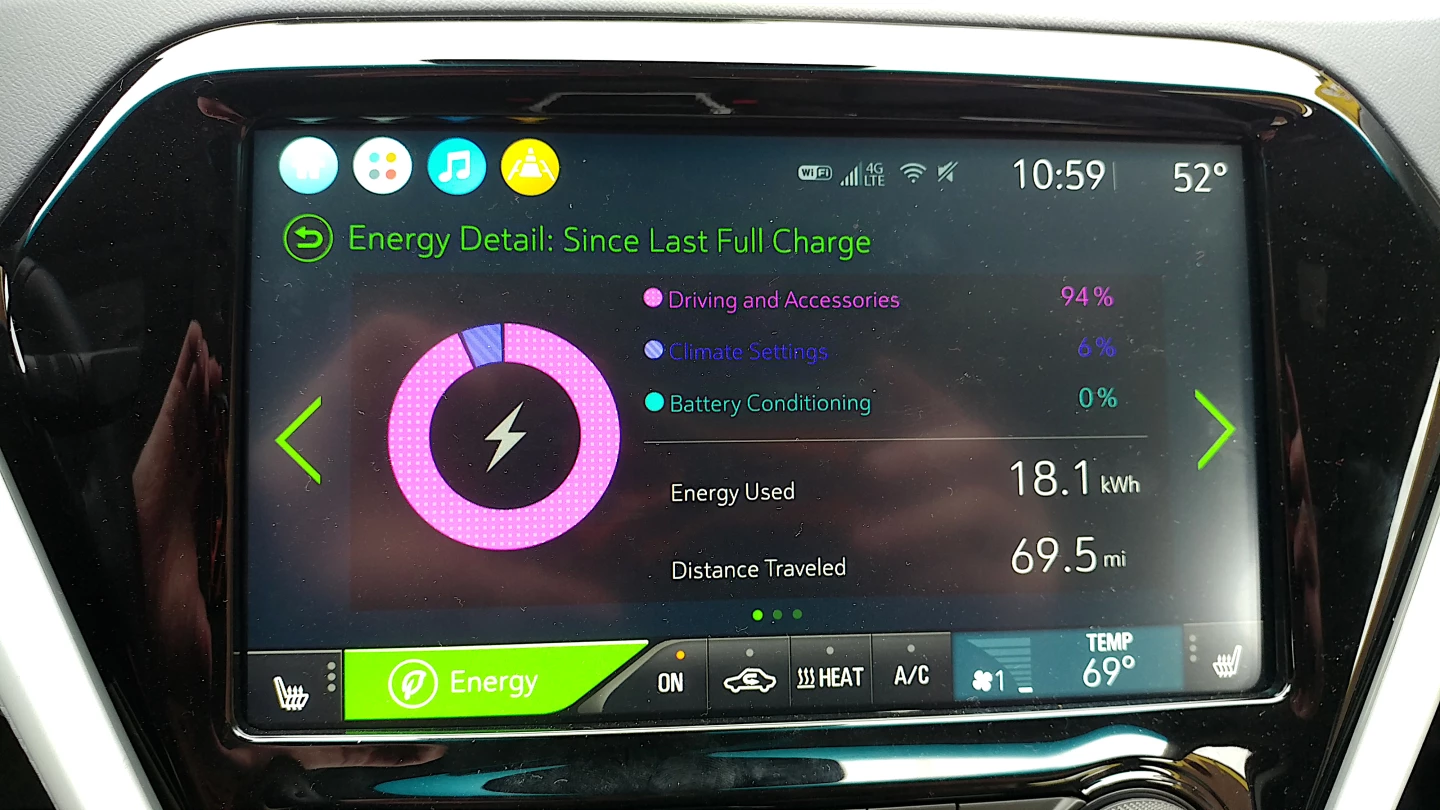

Thanks to Chevy’s well-done and very gamified in-vehicle charts and metrics for power usage, all being displayed on the 10.2-inch touchscreen, keeping track of how varied driving conditions affect overall range is easy. And it can be done on the fly. Thus it was learned that not running the climate control meant saving about 4.5 percent of range, and my personal driving style was further adding 1.3 percent to that range. The terrain, being hilly and varied, was a downer while the extensive highway driving was also reducing range, both dropping it by about 5 percent altogether. So the net gain was marginal at best. The remedy? Get off the freeway. Seemed logical.

After about 60 miles (96.5 km) of freeway usage, we moved to using side roads instead. That reduced speeds to 55 mph (88.5 km/h) or less. It also gave us a chance to see how well Android Auto can integrate mapping into the Bolt’s infotainment. The Bolt does not have its own navigation on board, relying instead on the user’s cell phone. There is an OnStar service from Chevrolet which can be used to map as well, but it requires a phone call from the car and clear reception. Since reception on our route was spotty and we had stopped to take photos and video anyway, it made more sense to use a phone.

Integration of Google Maps through Android Auto is always iffy (in our experience) and it didn’t work well in the Bolt. The audio piped through the Bluetooth connection just fine, which was good enough for our needs. Using Maps, rerouting away from freeways and going along more scenic side roads meant adding about 30 minutes to our total trip time, but also made for a better experience. There wasn’t an easy way to estimate range gain from the change, but we assumed that much of the 5 percent lost from speed and hills could be recovered. Later analysis showed we were partially right, gaining about 2 percent back. Most of our range losses were due to the terrain rather than the higher speeds. Had the freeway speed been much higher (75 mph or more), the entire scenario would have been far different.

Proceeding along the off-freeway route, we made it to the Washington-Oregon state border. Before heading over that border, we turned off-route and headed into nearby Long Beach, Washington. We found a ChargePoint charging station and pulled in to hook up. We didn’t plan to fully recharge, just make a quick stop. We used the bathroom break opportunity afforded, grabbed a coffee, and then unplugged and continued on. In all, we charged for about 7 or 8 minutes and gained about 15 to 20 miles (24 to 32 km) of charge out of that. Accounting for the detour, that was a net gain of about 8 or 9 miles (13 or 14 km) in all. Probably not worth the trouble if the point was to add more charge. We mostly did it for the coffee.

Driving across the 4-mile-long Astoria-Megler bridge, we officially entered Oregon and marked 192 miles (309 km) of driving on our journey. We had about 30 more to go to get to our next stop in Cannon Beach, Oregon. It’s a scenic drive along the coast of northern Oregon, and well worth the time taken.

Cannon Beach was our final destination for the day and, somehow, we arrived with almost 50 miles (80 km) of charge left on the 2020 Bolt EV. This was thanks largely to the use of the Bolt’s “Low Mode” and one-pedal driving to gain as much battery regen as possible. We were by no means hypermiling this drive, but using some common sense did pay off. We plugged in at Cannon Beach and checked into a hotel on the oceanfront. Because the chargers were in high demand and we had only the 80-ish miles from the beach to the Portland airport, we didn’t leave the car plugged in overnight. After a couple of hours, the MyChevrolet app showed the Bolt had about 120 miles (193 km) of range available – so we unplugged and moved the car so another vehicle could use the plug.

The next morning, hitting the road very early to make the airport before 11, I reviewed what had been learned and thought about the 2020 Chevrolet Bolt EV as a car. Not as an electric car, but instead as I would consider any other car.

My personal feeling was that the Bolt is a good car for the compact segments. It needs some improvement, namely in noise reduction, but is otherwise very well done. There’s plenty of cargo space, lots of passenger space, plus the driving interface and controls layout is intuitive. The large greenhouse means visibility is very good, and the overall feel of the car while on the road is nicely done. The Bolt is surprisingly quick too, accelerating to 60 mph (96.5 km/h) in under 7 seconds without really trying, and it handles much better than most non-sports options in the compact segments. That’s largely to its design, which is low-slung (in terms of mass distribution) and responsive.

At $37,495 (before incentives) and with two trim levels to choose from, the 2020 Bolt EV is a solid investment. There is some adjustment required when moving from gasoline to a battery electric vehicle, but given the exceptional range of the Bolt, that transition is not as steep as it could be.

Product Page: Chevrolet Bolt EV