In the quest to combat Alzheimer's disease, researchers have been hopeful about the use of antibodies to destroy peptides in the brain that cause damaging tangles and plaque buildups. So far though, such treatments have been unsuccessful. Postulating that the issue had to do with the antibodies getting blocked by the blood-brain barrier, scientists have found a way to sneak them into the brains of mice afflicted with the disease, and have seen encouraging results.

Using antibodies to treat the amyloid beta peptides that lead to plaques in the brains of Alzheimer's patients has been a promising idea in the medical community for a few years now, but one with results that have been largely disappointing. Last year was the first time a monoclonal antibody drug showed some promise in slowing the cognitive decline associated with the disease, but just a few months after that development, drug maker Roche announced the failure of a massive Phase 3 clinical trial for its own anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody drug.

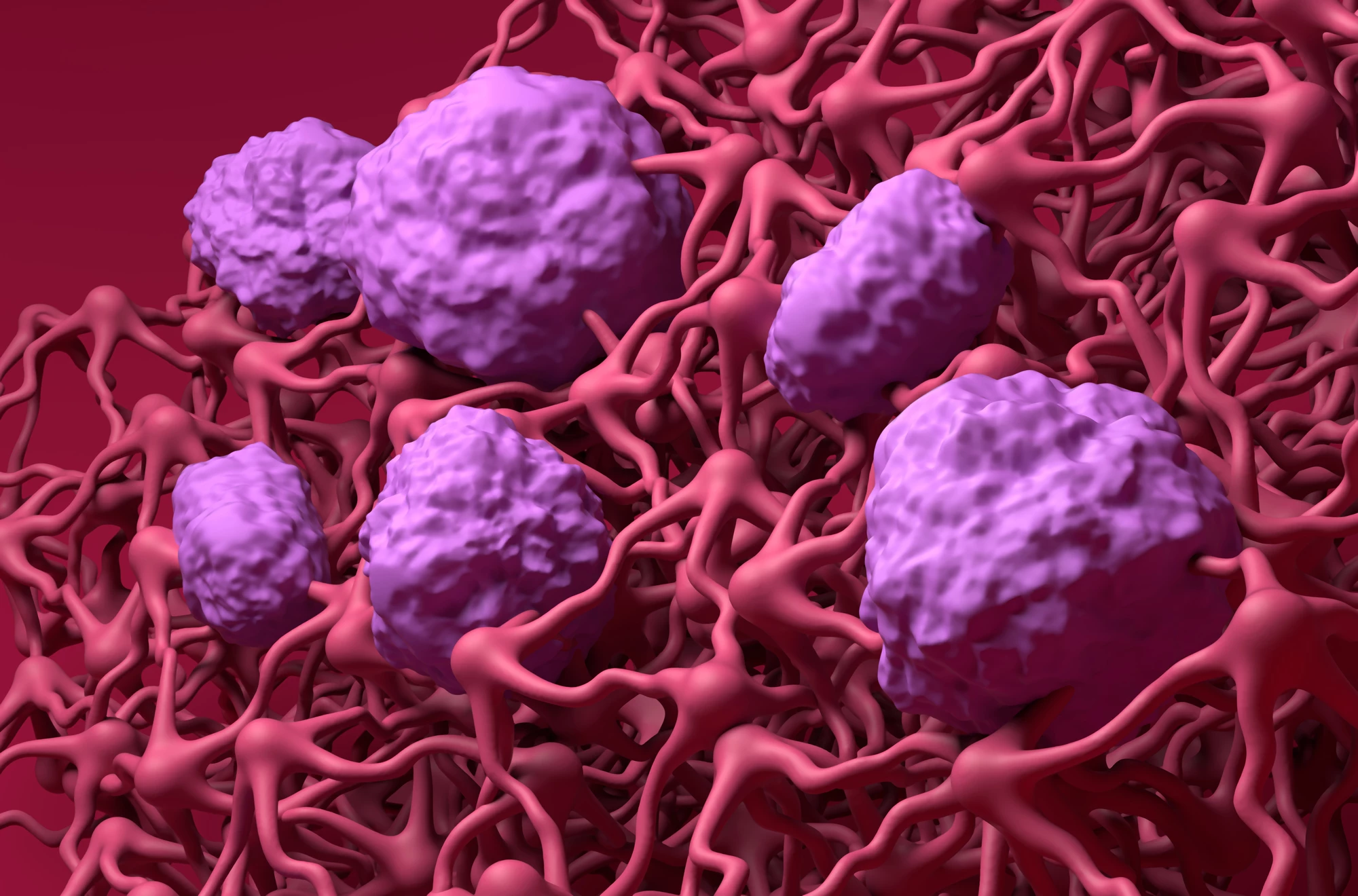

However, because antibodies are so successful at fighting off other unwanted substances in the body, from malaria to the signaling molecules involved in rheumatoid arthritis, scientists haven't given up on using them to blast away the amyloid beta peptides.

Thinking the issue might have to do with the fact that the amyloid-fighting antibodies may be too large to pass through the blood-brain barrier, researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University hid smaller portions of them inside round nanoparticles known as nanomicelles, which were glucosylated (linked with sugar molecules). They then injected these particles into mice afflicted with Alzheimer's disease, over the course of 10 weeks.

The research team not only found that the injections reduced the amounts of amyloid beta peptides in the brain, but that there was also a reduction in size and density of the plaques that did wind up forming. What's more, they also found that the treated mice had better learning and spatial memory skills than the untreated mice, which means the treatment might not only slow the disease, but temper its symptoms as well. Of course, human trials will be necessary to reveal whether or not the treatment works on us.

The researchers say that their sugar-based nanomicelles could also be filled with other drugs that degrade amyloid beta peptides in the brain, thus opening a new channel for research into treating Alzheimer's.

Their work has been published in the Journal of Nanobiotechnology.