A new review article penned by a trio of researchers suggests insects do have the capacity to experience pain. The article summarizes the latest behavioral and molecular science before concluding the potential of pain states in insects could have ethical implications for current farming and research practices.

The new article first clarifies the important distinction between what is called nociception, and the negative subjective experience of pain. Nociception was defined more than a century ago as a way of separating the physiological process of sensing damaging stimuli from the subjective felt experience of pain.

Nociception is often accompanied by feelings of pain in humans and animals. However, in more simple organisms it is difficult to infer whether a simple nociceptive reflex is felt like pain. All insects have been found to display nociceptive responses. If you heat up the floor in an enclosure containing a fruit fly, for example, that fly will quickly move away from the hot surface. This is an example of nocifensive behavior, proving insects do respond to damaging stimuli.

But how do we distinguish a simple reflex from a more complex pain experience? Here, the new article refers to a concept called “descending order of nociception”.

This concept refers to a kind of higher level of nervous system activity where an organism can adjust its nociceptive processing depending on a given situation. Speaking to Newsweek, lead author on the study Matilda Gibbons said the ability to turn down a nociceptive reflex and alter one's behavior is a useful sign an organism has the ability to subjectively experience pain.

"One hallmark of human pain perception is that it can be modulated by nerve signals from the brain," Gibbons noted. "Soldiers are sometimes oblivious to serious injuries in the battlefield since the body's own opiates suppress the nociceptive signal. You can also consciously 'grit your teeth' and bear the pain, in case such 'heroic' behavior earns you a reward or prestige. We thus asked if the insect brain contains the nerve mechanisms that would make the experience of a pain-like perception plausible, rather than just basic nociception."

After outlining a number of insect behaviors that clearly demonstrate nociceptive dampening processes, the new article presents several pieces of research to explain the molecular mechanisms at work. Unlike mammals, insects do not have any genes that code for opioid receptors. So other neurochemical mechanisms must be at play. A number of neuropeptides are hypothesized as possible nociception modulators in insects. These include drosulfakinin, allatostatin-C, and leucokinin, all molecules found to influence insect behavior.

The review suggests the presence of descending nociception controls in insects makes it plausible to consider they experience some sensation of pain. Certain behaviors known to be mediated by descending nociceptive controls, and used to quantify pain in animals such as mice, are seen in insects. Reduced feeding patterns in mice, for example, are often used as an indicator of pain, and insects have also been seen to display reduced responses to food stimuli following nociceptive experiences.

Ultimately, the review gestures toward a radical revision of how insects are treated in both farming and research contexts. Co-author on the article Sajedeh Sarlak said it is crucial more research is done to understand these nociceptive processes in insects as mass production of these organisms for food is rapidly increasing around the world.

“…the ethical implications have so far not been considered, in part because many decision-makers' view is that there are none to consider for insects," Sarlak noted to Newsweek. "We need to understand: are insects capable of the experiences of pain and suffering, to ensure that the ethical mistakes of conventional battery livestock farming are not repeated."

The new article encapsulates a growing body of research that may cause many governments to reevaluate animal welfare policies. Last year the UK government added a number of invertebrates to its animal welfare protections following an independent review.

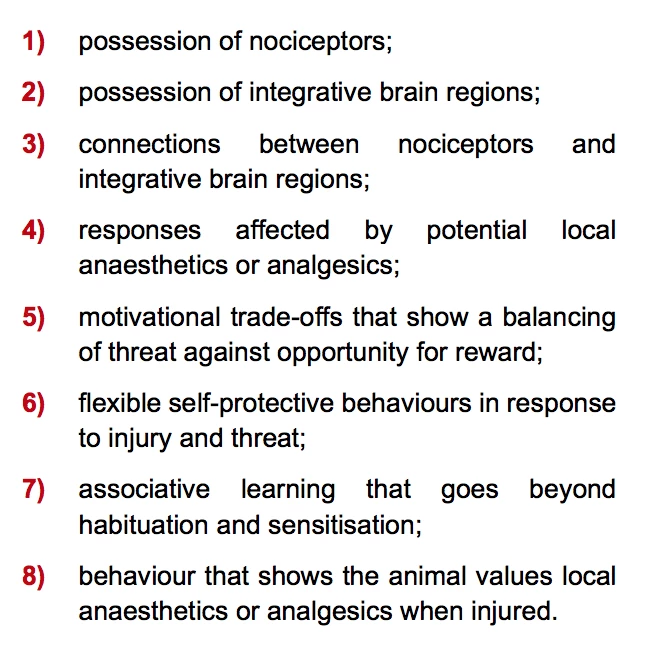

The review presented eight criteria by which animal sentience can be established. Here, sentience was defined as the capacity to feel emotions such as distress, and the review ultimately concluded crabs, octopuses, and lobsters should all be considered sentient with the welfare protections that affords.

The new article was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B (preprint link here).