Researchers at Columbia University Irving Medical Center have identified the specific neurons in mice brains that tell them they've eaten enough. This fascinating discovery could play a big role in the future of weight loss treatments for humans.

Unlike most cells in the brain that send and receive specific signals to the body about eating, these are unique in their function.

“Other neurons in the brain are usually restricted to sensing food put into our mouth, or how food fills the gut, or the nutrition obtained from food,” explained physicist Alexander Nectow, who led the study. “The neurons we found are special in that they seem to integrate all these different pieces of information and more.“

Finding the brain's portion control system

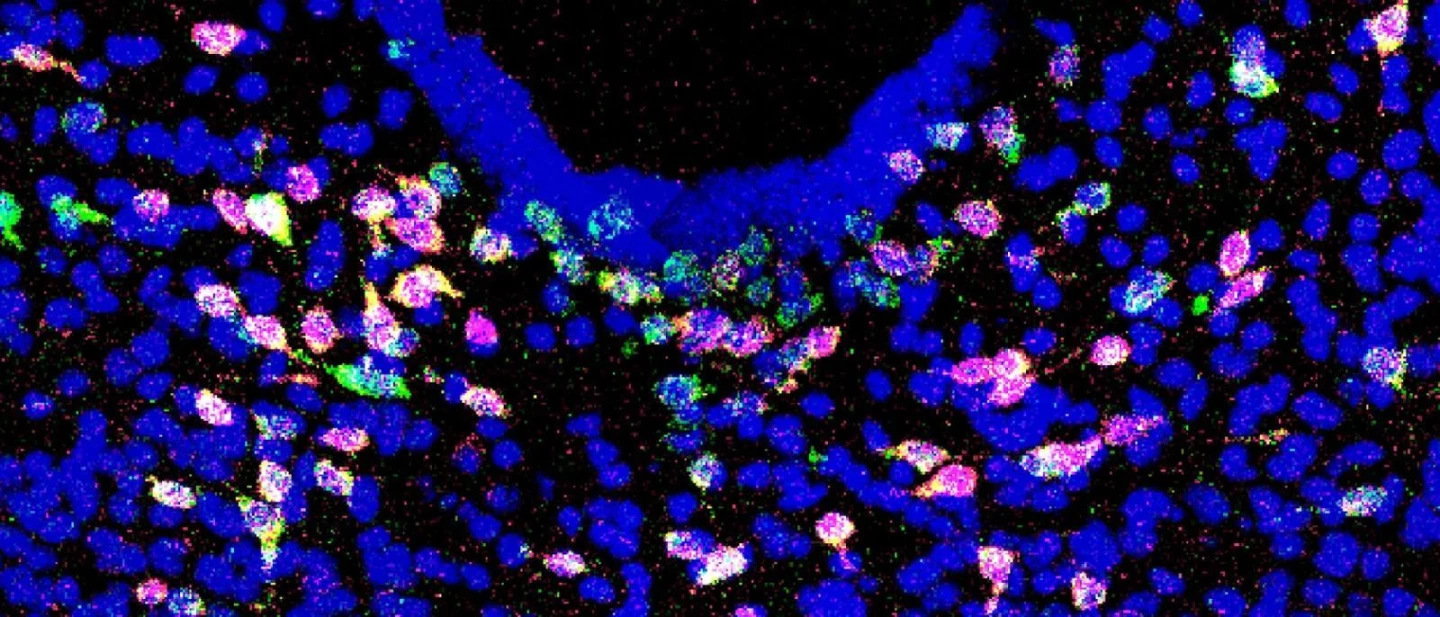

Using a new technique called spatially resolved molecular profiling, the Columbia scientists were able to peer into the brainstem – which connects the brain to the spinal cord and controls vital functions – and discern the different types of cells in there, down to their molecular composition. This was previously not possible.

This profiling method revealed cells that were similar to neurons responsible for regulating satiation, but were slightly different. Naturally, they had to then investigate their functions more closely.

Specifically, as the researchers noted "... a population of neuropeptidergic neurons in the brainstem’s dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN)" in their paper published in the journal Cell. "These neurons track food from sensory presentation through ingestion, integrate these signals with slower-acting humoral cues, and express cholecystokinin (CCK)," revealed the team. "These CCK neurons bidirectionally regulate meal size, driving a sustained meal termination signal with a built-in delay."

A link to Ozempic?

For those whose thoughts immediately wandered to 'Ozempic,' I'm with you.

Ozempic is a medication used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity, belonging to a class of drugs called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. These drugs mimic the effects of the GLP-1 hormone, which is naturally released from the gut after eating. One of the key effects of GLP-1 is to promote satiety and reduce food intake.

Those CCK neurons are activated by Exendin-4, a GLP-1 agonist. This suggests that one way GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic reduce appetite is by activating these specific CCK neurons.

The study's identification of CCK neurons as a key component of the satiation circuitry provides a potential mechanism for understanding how GLP-1 agonists achieve this effect.

Experimenting with light

The researchers got the mice brains to express light-sensitive proteins in the CCK-expressing neurons. They then implanted optical fibers into that part of the brain, so they could deliver light directly to the targeted neurons and activate the neurons for their experiments.

When their neurons were activated by the light, the mice ate much smaller meals. The scientists noted that the neurons also tracked each bite of food, and combined multiple data points to carry out their satiation signaling.

“Essentially these neurons can smell food, see food, feel food in the mouth and in the gut, and interpret all the gut hormones that are released in response to eating,” Nectow said. ”And ultimately, they leverage all of this information to decide when enough is enough.”

A (potential) win in the war against obesity

Given that the brainstem is built the same in all vertebrates, it's safe to assume humans have satiation-regulation neurons that work just like the ones observed in mice.

That's promising, given the growing need for weight loss and obesity treatments in humans. According to the World Health Organization, 43% of people aged 18 and up were overweight as of 2022; 16% were estimated to be living with obesity. Those figures illustrate how global adult obesity has more than doubled since 1990.

Ozempic has been shown to be effective for helping people lose weight, alleviating osteoarthritic knee pain, and even reducing the risk of kidney failure and several obesity-associated cancers in type 2 diabetics. However, it's also been linked to sudden vision loss, and a high risk of suicidal thoughts.

Clearly, we've got a long way to go before we fully understand this class of medications. Hopefully, this new discovery will help shed more light on their workings. And as Nectow explains, "it could be used for obesity therapies down the road.”