A house made of mucus may not sound like a desirable abode, yet researchers have found that the crafty animal creating such an unappealing structure may help engineers design cheaper and more efficient pumps for vital industrial applications like water filtration.

Researchers from the University of Oregon (UO) have found that the unique feeding behaviors of Oikopleura dioica, a 1-mm-long filter-feeding marine larvacean, could help engineers design more efficient peristaltic pumps, which are common in industrial settings that require fluid treatment.

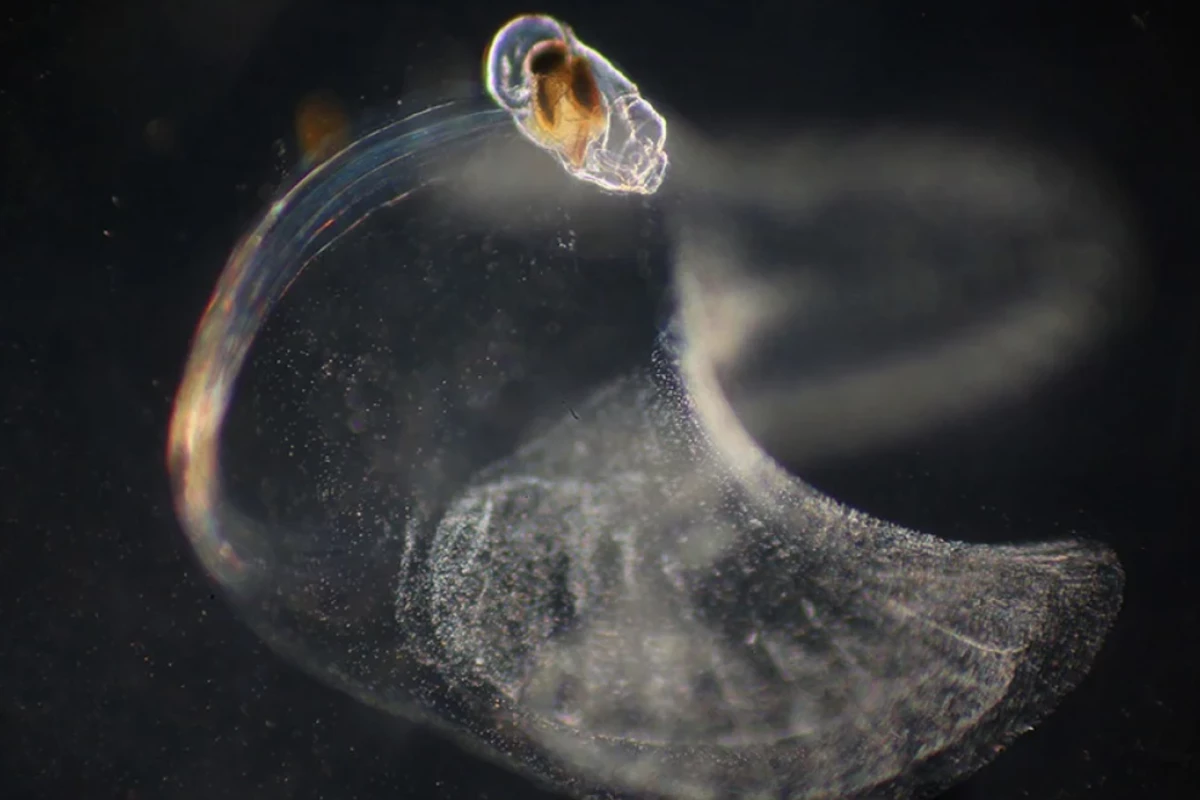

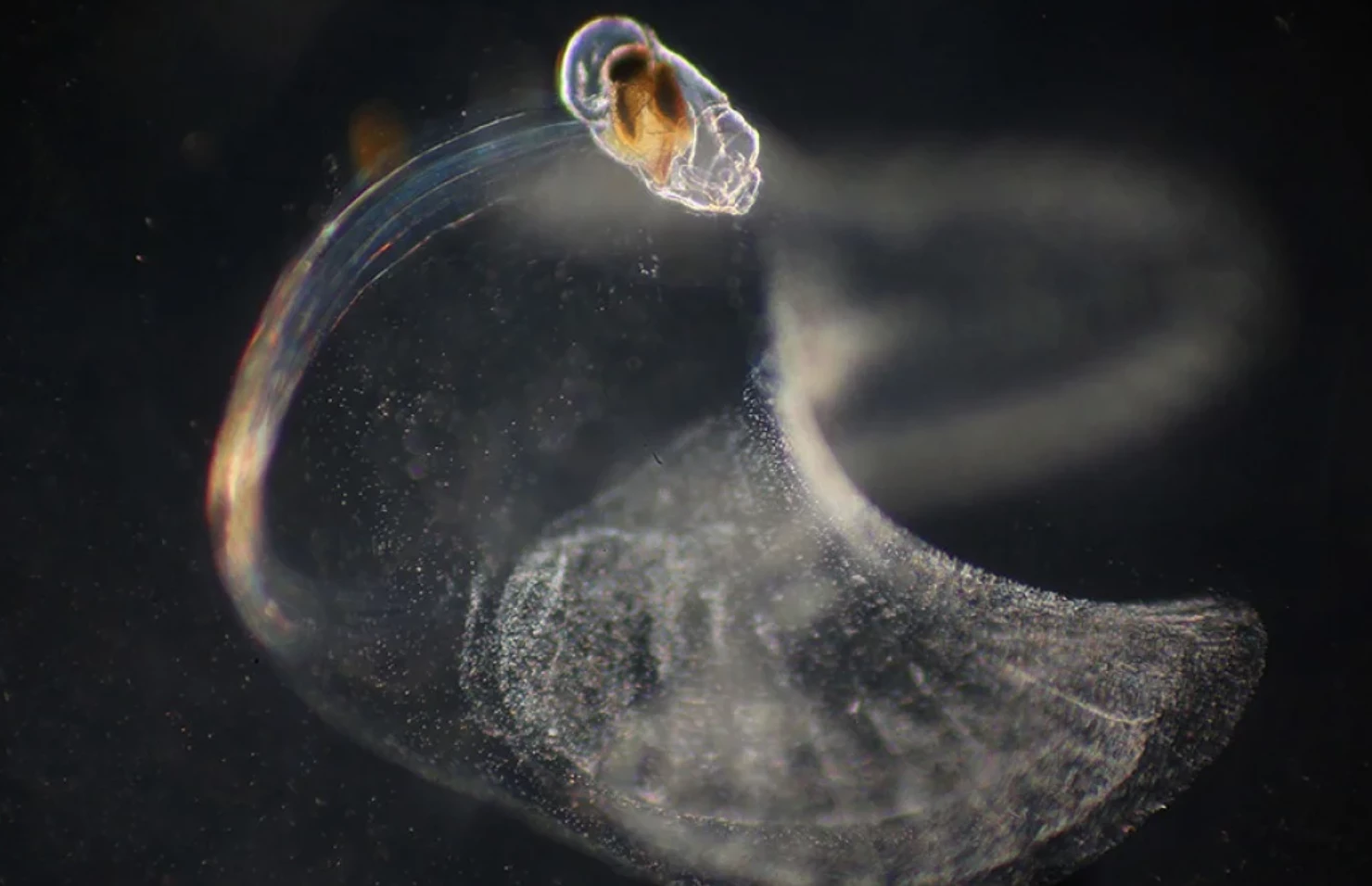

Generally, these positive displacement pumps require external squeezing to move fluid forward through the system. In the tadpole-like O. dioica, the propulsion is driven by the animal’s tail inside a mucus cocoon it constructs many times a day in order to filter feed.

“Pumps are everywhere in nature, but this pump is unique in driving fluid through a filter by beating a tail inside a sealed chamber,” said Kelly Sutherland, a biologist at UO’s Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. “Plus, the animals are so mesmerizing to observe.”

While a gelatinous bubble of mucus suspended in water may not scream “mesmerizing,” it’s a crafty bit of biological engineering. Every three or four hours, the animal creates this ‘snot palace’ around its body, using its tail to first inflate the structure and then to propel fluid containing food particles forward towards its mouth. When the mucus case has served its purpose, it slides out through an escape hatch.

“It’s so cool. It’s a pretty complex structure,” said Terra Hiebert, a research associate at UO.

The researchers discovered the workings of this snot palace in Bergen, Norway, at a facility breeding the animals to study. Using microscopes and high-speed video capture, the scientists were able to see just how well the animal’s tail directed water and a particle flow, revealing what a special pump system it had mastered.

While the dominant tail fits inside the structure, it makes contact with the sides that seal and unseal the chamber at various key points. These seals build pressure and control fluid movement, preventing backward flow.

“They use this relatively unique pumping strategy, with a sinusoidal tail and a snug fit within chamber,” Hiebert said. “Because of the snug fit, there's very little backward displacement of water.”

The researchers believe that mimicking this sort of action could see the development of more efficient pumps that shield moving parts from wear and tear.

“This new understanding of larvacean pumps helps us understand the ecological success of a widespread organism and may even inspire the next generation of water or air filters in the built environment,” Sutherland said.

The research was published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. - and to see the tiny animal in action, check out the video below.

Source: University of Oregon