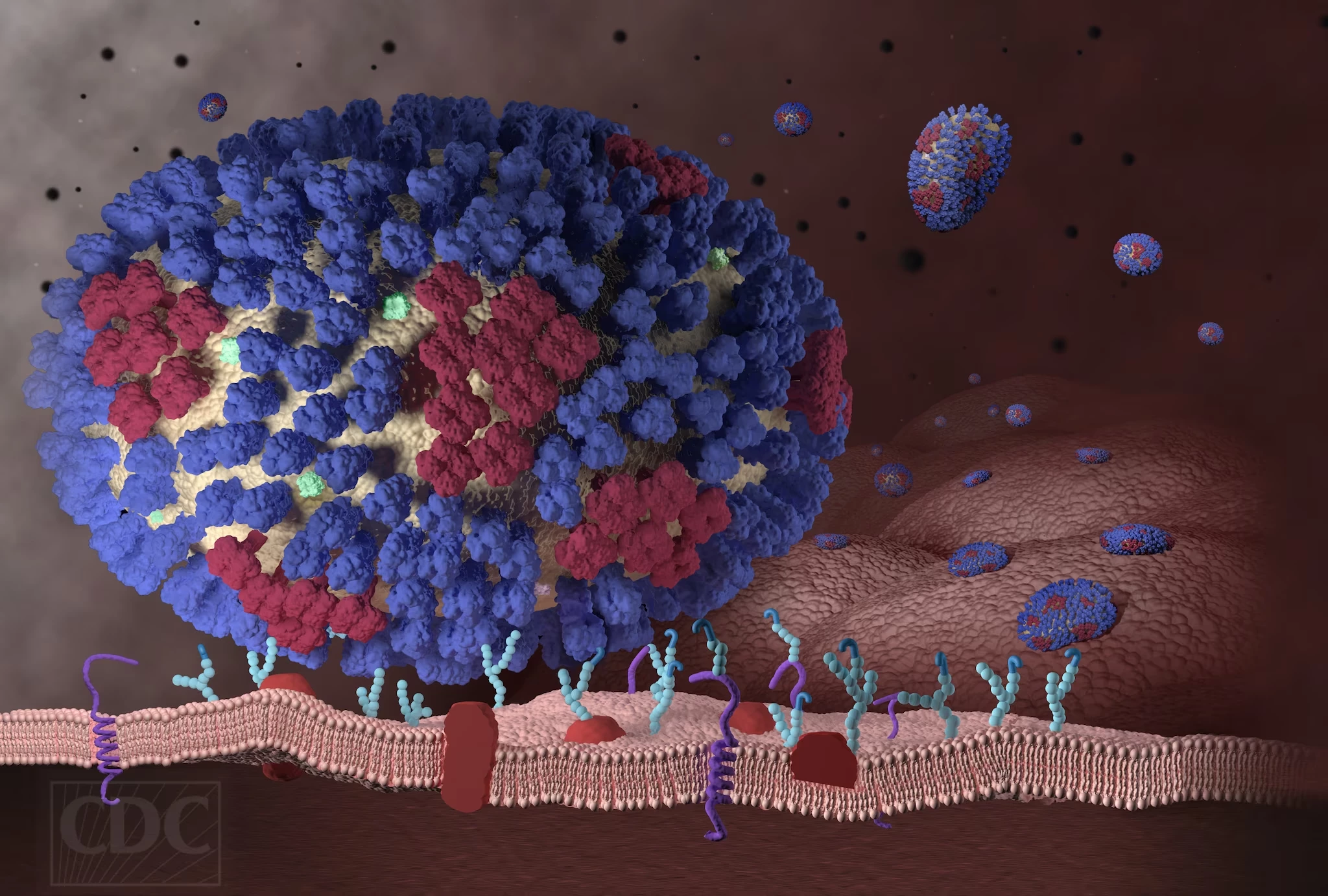

The influenza A virus is one of the most persistent and infectious bugs around the world. Researchers have just uncovered how it's able to thrive by slicing and dicing genetic material inside our cells while keeping itself intact. The finding might open a new pathway to combating the virus.

According to the World Health Organization, the flu causes three to five million cases of severe illness each year, with 290,000-650,000 deaths from respiratory complications.

The two main viruses that cause the flu — influenza A and B — have existed for centuries and, although some antiviral advances have been made, these bugs have proven extremely difficult to eradicate. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) have identified at least one secret to the success of influenza A, a finding that might arm researchers with another way to combat it.

The finding hinges on understanding how the virus is able to wield a protein known as PA-X to make myriad cuts in the RNA of host cells without harming its own RNA.

Host shutoff

When the flu bug uses this protein to slice up the RNA in its host, it is able to keep the RNA from doing one of its key jobs when it comes to infections – triggering the immune system to fight the bug. It also allows the virus to take over the host cell and create copies of itself in a process known as host shutoff. Yet, somehow the protein doesn't affect the virus' own RNA.

What the researchers found is that the RNA sequence targeted by PA-X is extremely specific. In fact, it's one that exists in abundance in humans and other animals susceptible to infection by the virus, but one that is barely found in the virus' own RNA.

If researchers can learn to block this scalpel-like precision of PA-X, they may come up with a tool that can help bolster our defenses against influenza A.

Flipping the script

The UW-Madison findings further shed light on an ability that's not been seen in viruses before called self/non-self recognition. It refers to a mechanism by which the virus can differentiate between its own RNA and that of its host. While it's been seen in reverse – host cells being able to tell the difference between themselves and viruses – knowing that the virus itself can do it is new information.

"It's interesting to see the virus also has found a way to do that, flipping the script," said lead author, Marta Gaglia, a UW-Madison associate professor of medical microbiology and immunology.

The team plans to continue its research focused on PA-X and hopes to unravel how the protein and the sequences of RNA it acts on might help identify stronger and weaker strains of the flu.

"An ideal world that we would like to get to is: If you give me a sequence, I could take a look and say, 'This is a really active version,' or, 'This is a less active version,'" said Gaglia. "And in simplistic terms, that could indicate whether it could be a more dangerous strain."

The research has been published in the journal Nature Microbiology.

Source: UW-Madison