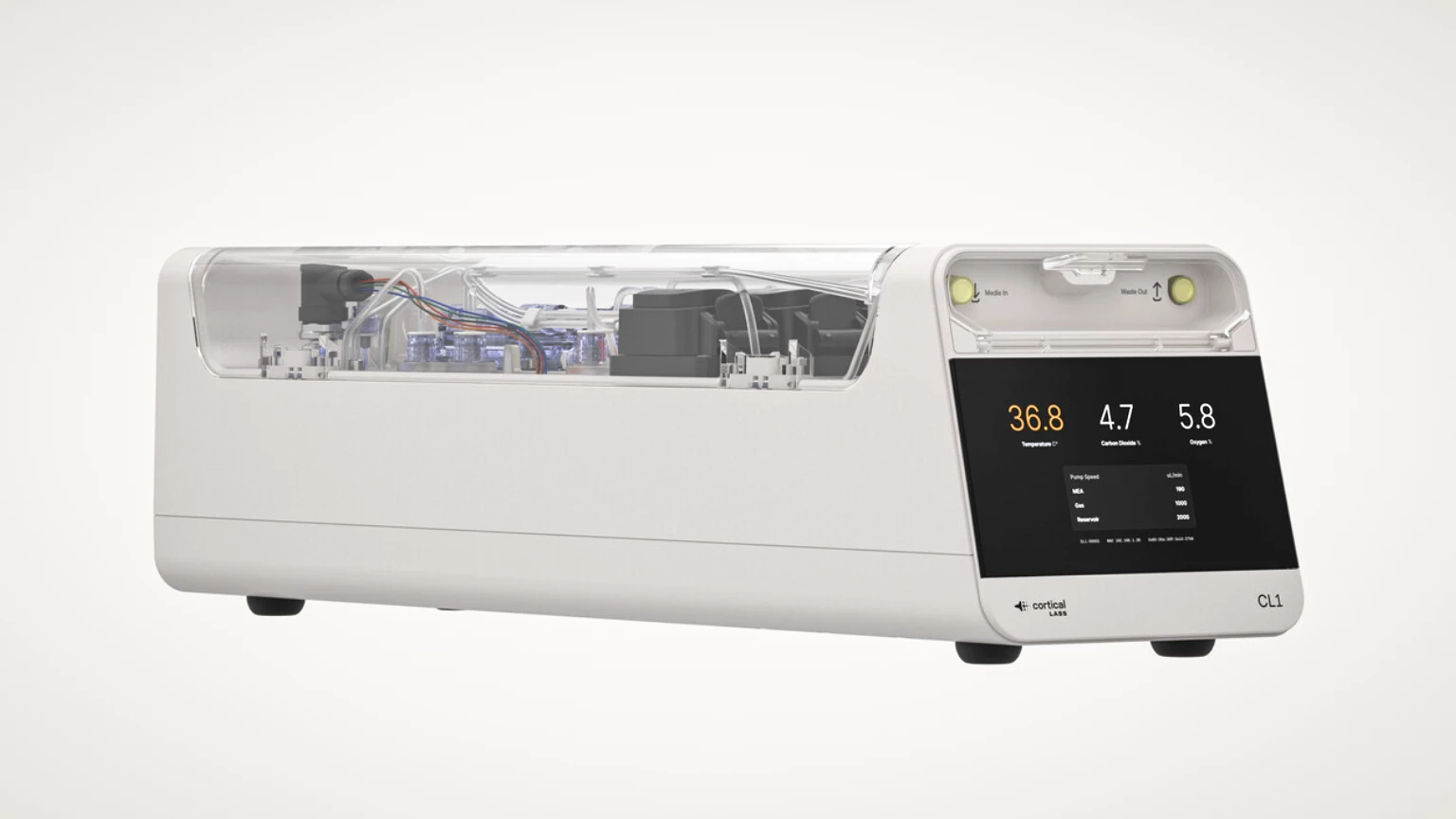

The world's first "biological computer" that fuses human brain cells with silicon hardware to form fluid neural networks has been commercially launched, ushering in a new age of AI technology. The CL1, from Australian company Cortical Labs, offers a whole new kind of computing intelligence – one that's more dynamic, sustainable and energy efficient than any AI that currently exists – and we will start to see its potential when it's in users' hands in the coming months.

Known as a Synthetic Biological Intelligence (SBI), Cortical's CL1 system was officially launched in Barcelona on March 2, 2025, and is expected to be a game-changer for science and medical research. The human-cell neural networks that form on the silicon "chip" are essentially an ever-evolving organic computer, and the engineers behind it say it learns so quickly and flexibly that it completely outpaces the silicon-based AI chips used to train existing large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT.

“Today is the culmination of a vision that has powered Cortical Labs for almost six years," said Cortical founder and CEO Dr Hon Weng Chong. "We’ve enjoyed a series of critical breakthroughs in recent years, most notably our research in the journal Neuron, through which cultures were embedded in a simulated game-world, and were provided with electrophysiological stimulation and recording to mimic the arcade game Pong. However, our long-term mission has been to democratize this technology, making it accessible to researchers without specialized hardware and software. The CL1 is the realization of that mission."

He added that while this is a groundbreaking step forward, the full extent of the SBI system won't be seen until it's in users' hands.

"We’re offering 'Wetware-as-a-Service' (WaaS)," he added – customers will be able to buy the CL-1 biocomputer outright, or simply buy time on the chips, accessing them remotely to work with the cultured cell technology via the cloud. "This platform will enable the millions of researchers, innovators and big-thinkers around the world to turn the CL1’s potential into tangible, real-word impact. We’ll provide the platform and support for them to invest in R&D and drive new breakthroughs and research.”

These remarkable brain-cell biocomputers could revolutionize everything from drug discovery and clinical testing to how robotic "intelligence" is built, allowing unlimited personalization depending on need. The CL1, which will be widely available in the second half of 2025, is an enormous achievement for Cortical – and as New Atlas saw recently with a visit to the company's Melbourne headquarters – the potential here is much more far-reaching than Pong.

The team made international headlines in 2022 after developing a self-adapting computer 'brain' by placing 800,000 human and mouse neurons on a chip and training this network to play the video game. New Atlas readers may already be familiar with Cortical Labs and its formative steps towards SBI, with Loz Blain covering the early advances of this self-adjusting neural network capable of adjusting and adapting to forge new, stimuli-responsive pathways in processing information.

“We almost view it actually as a kind of different form of life to let's say, animal or human,” Chief Scientific Officer Brett Kagan told Blain in 2023. “We think of it as a mechanical and engineering approach to intelligence. We're using the substrate of intelligence, which is biological neurons, but we're assembling them in a new way.”

Cortical Labs has come a long way since that important first step but now-obsolete DishBrain, both in technology and name. Now, with the commercialization of the CL1, researchers can get hands-on with the the technology, and start exploring a vast range of real-world applications.

When New Atlas visited Kagan and team at Cortical Labs’ Melbourne headquarters late last year in the lead-up to this launch, we saw first-hand how far the biotechnology has come since the DishBrain. The CL1 features relatively simple, stable hardware, new ways of optimizing "wetware” – human brain cells – and significant strides towards being able to grow a neural network that works like a fully functional brain. Or, as Kagan explained of a work in progress, the "Minimal Viable Brain."

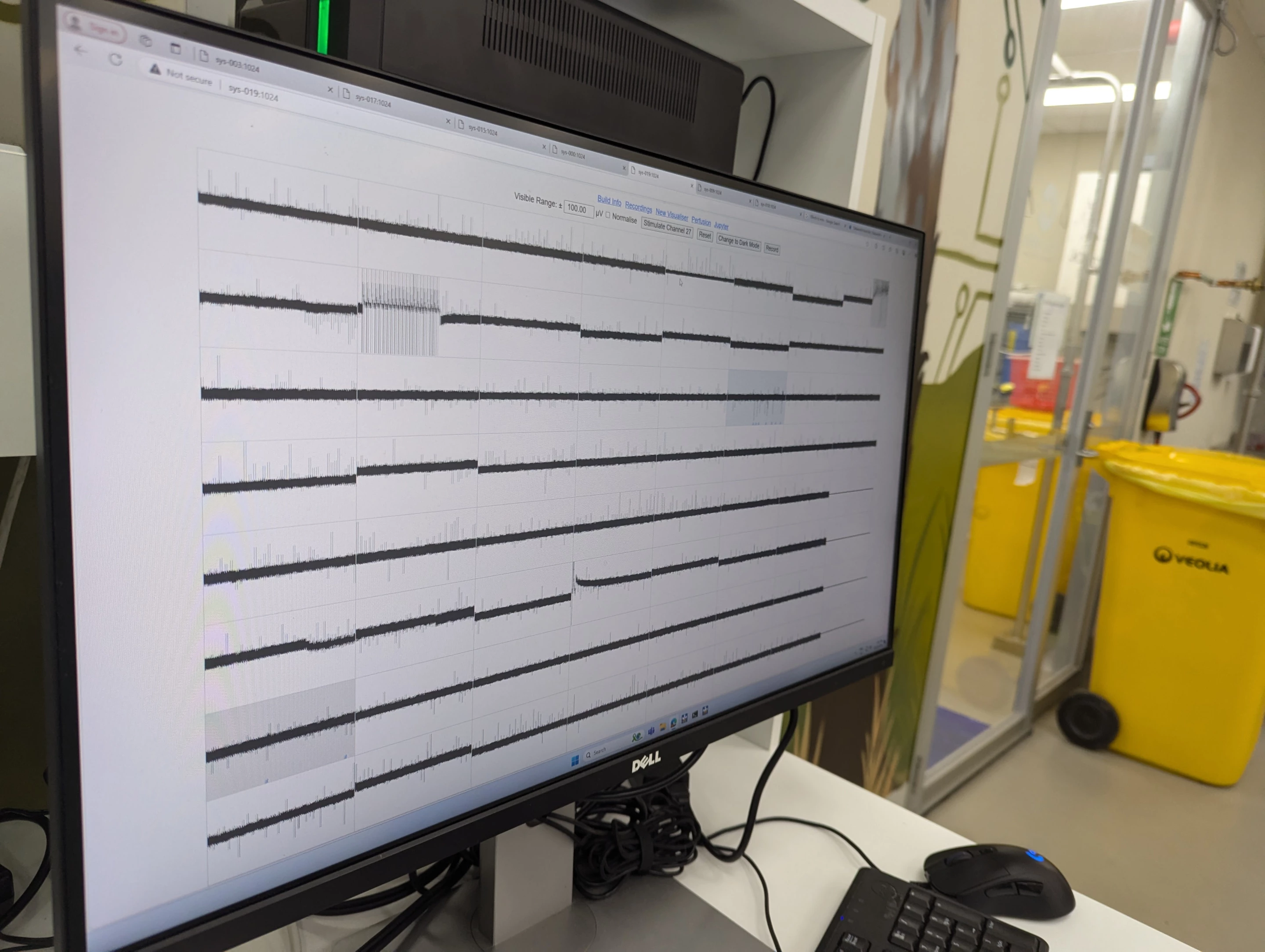

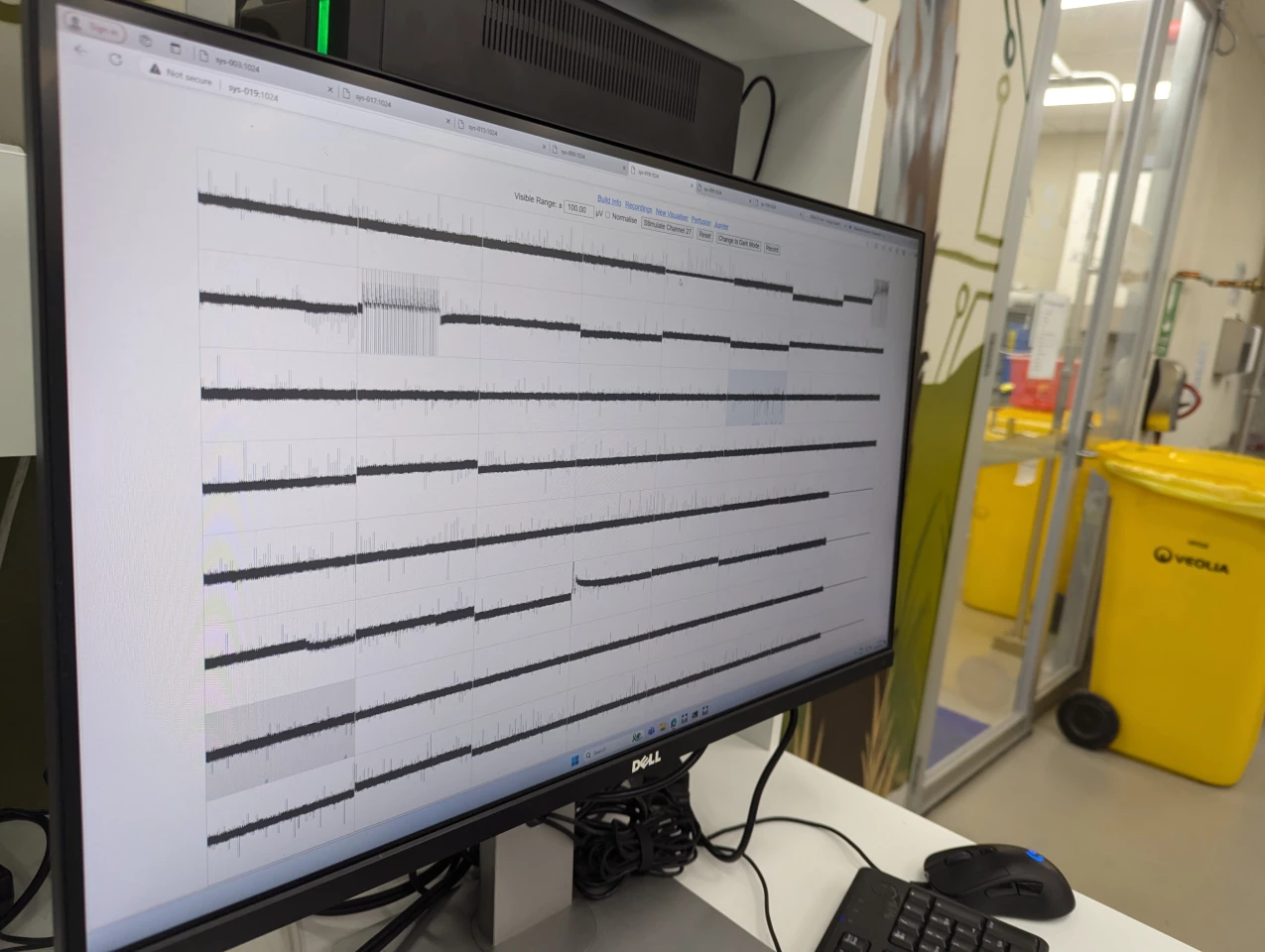

In 2022, the team demonstrated how rodent- and human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) integrated into high-density multielectrode arrays (HD-MEAs) based on complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology could be electro-physiologically stimulated to forge autonomous, highly efficient information-exchange paths.

To do so, they needed a way to reward the brain cells when they exhibited desired behaviors, and punish them when they failed a task. In the DishBrain experiments, they proved that predictability was the key; neurons seek out connections that produce energy-efficient, predictable outcomes and will adapt their networks in search of that reward, while avoiding behaviours that produce a random, chaotic electrical signal.

But, as Kagan explained, that was just the start.

“The current version is totally different technology,” Kagan told Blain and I. “The previous one used something called a CMOS chip, which basically gave you a really high-density read, but it was opaque, you couldn’t see the cells. And there were other issues as well – like, when you stimulate with a CMOS chip, you can't draw out the charge; you can't balance the charge as well. You end up with a build-up of charge at where you’re stimulating over long periods of time, and that’s pretty bad for the cells.

“With these versions, they're a much simpler technology, but that means they're much more stable and you're much more able to actively balance that charge,” he added. “When you put in two microamps of current, you can draw out 2 microamps of current. And you can keep it more stable for longer.”

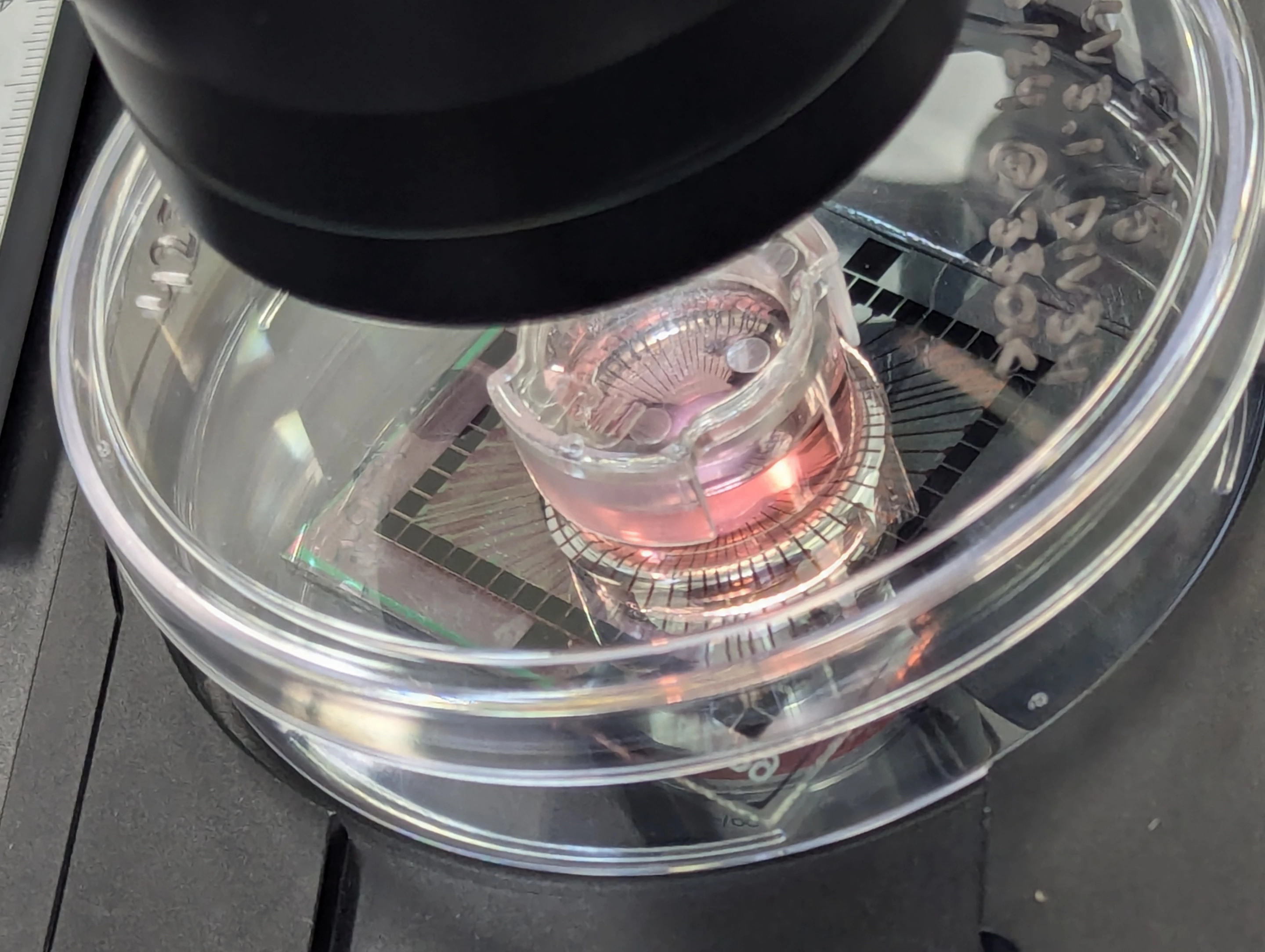

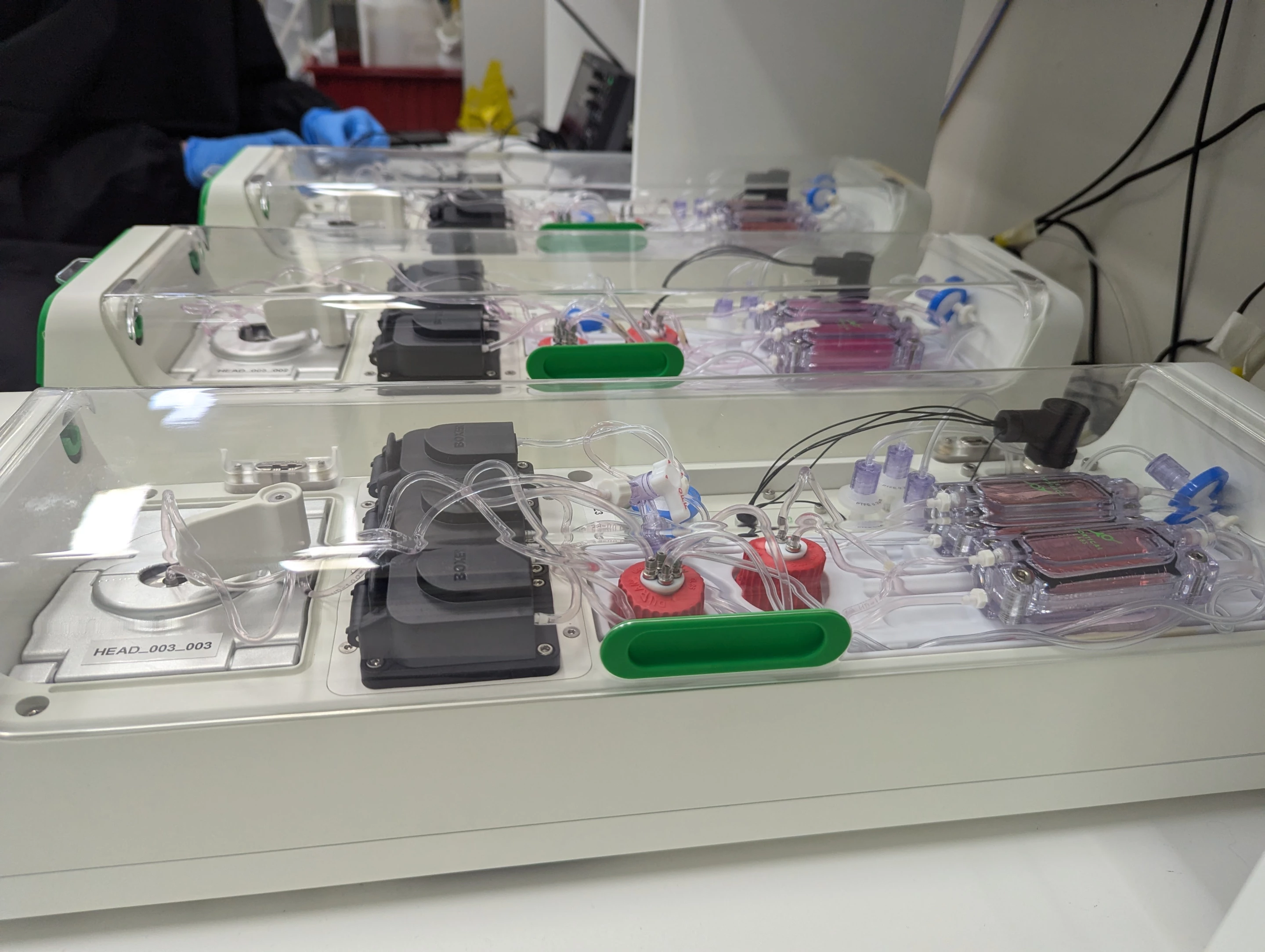

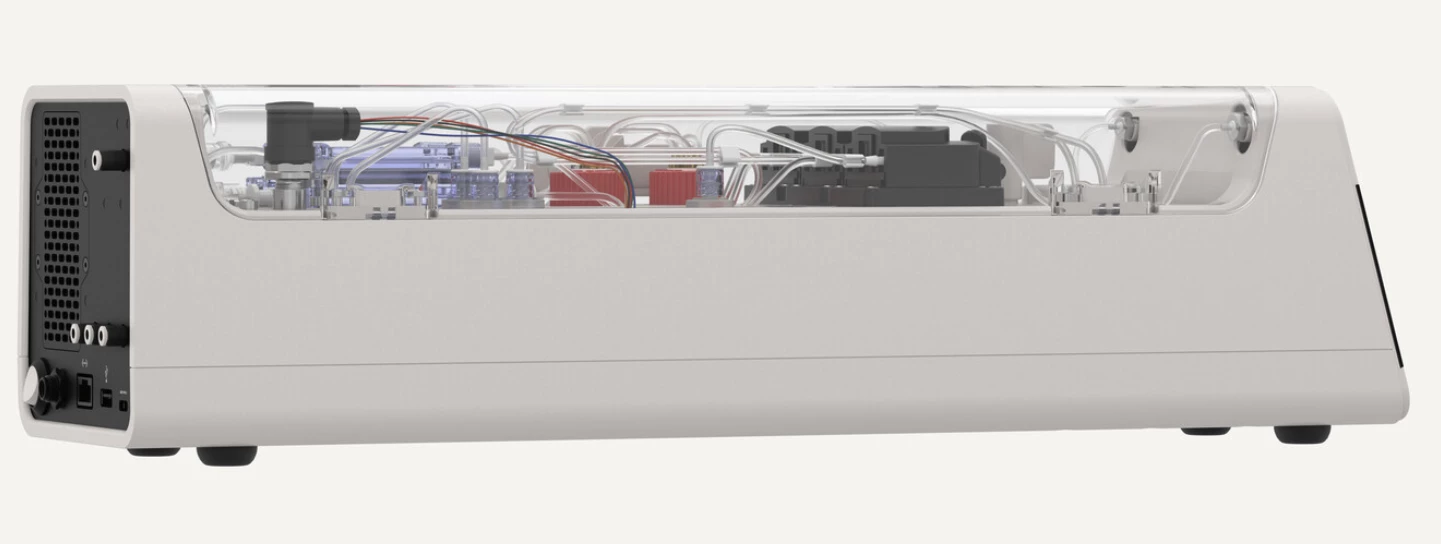

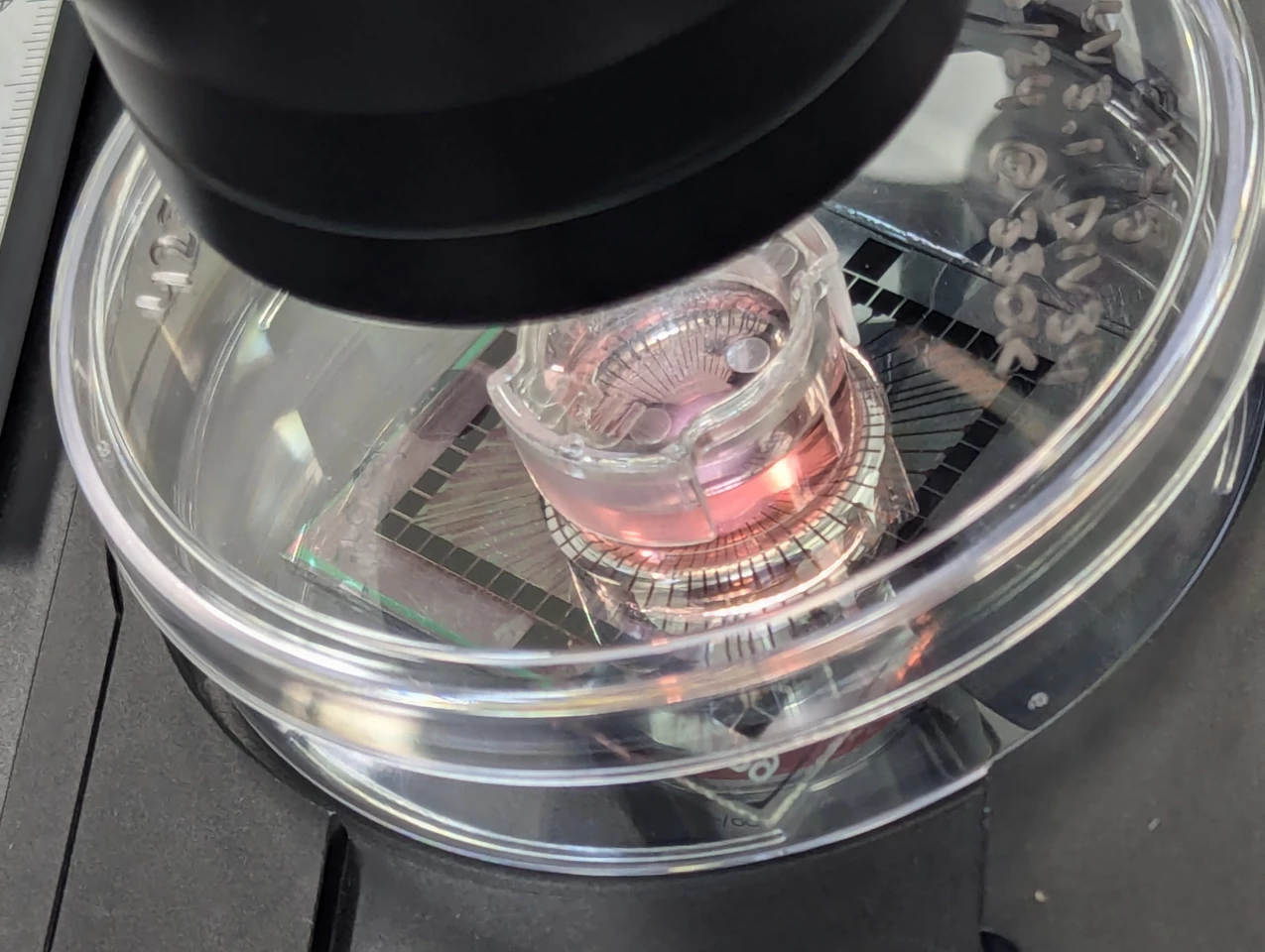

Inside the CL1 system, lab-grown neurons are placed on a planar electrode array – or, as Kagan explained, “basically just metal and glass.” Here, 59 electrodes form the basis of a more stable network, offering the user a high degree of control in activating the neural network. This SBI "brain" is then placed in a rectangular life-support unit, which is then connected to a software-based system to be operated in real time.

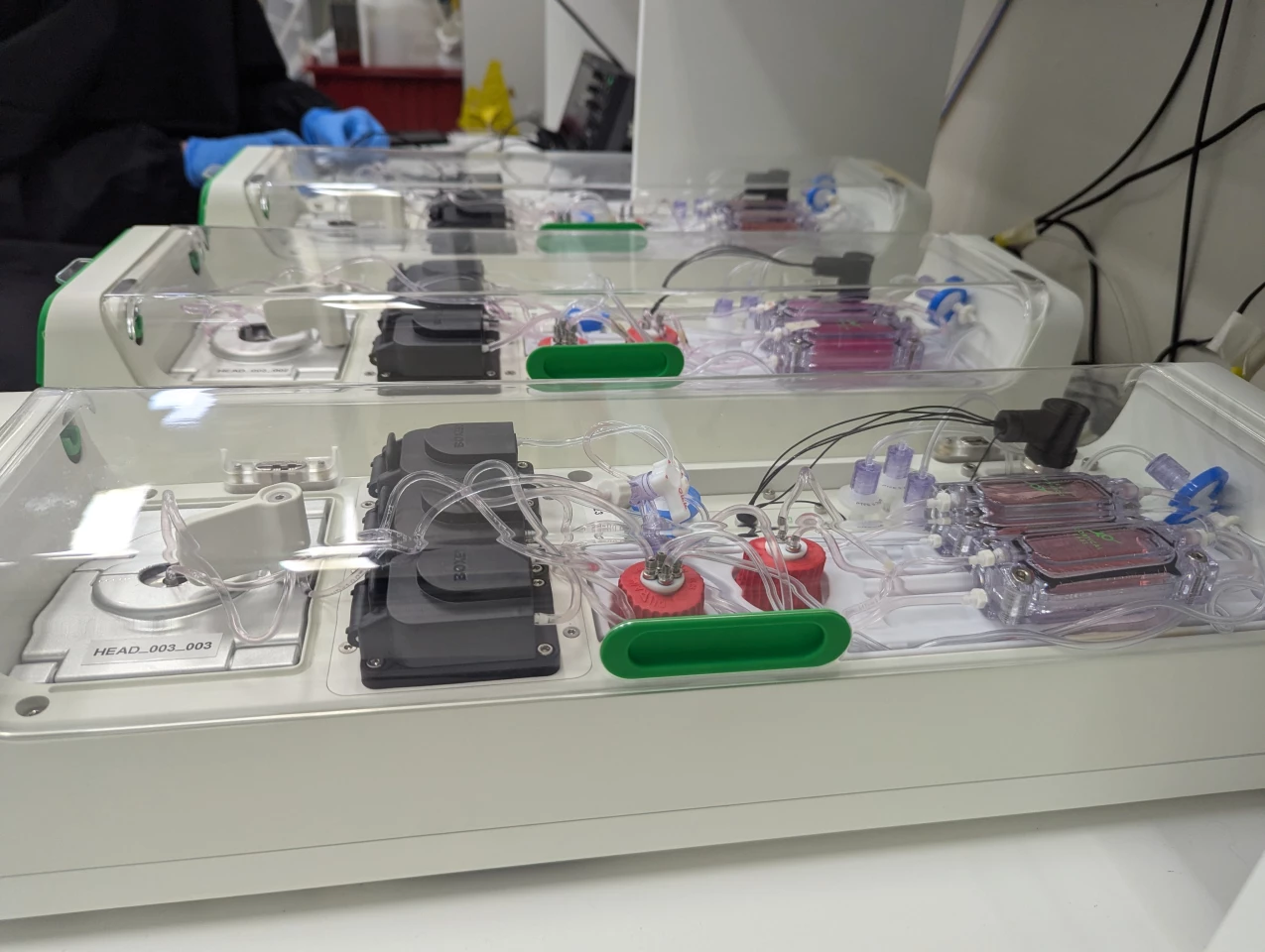

"The perfusion circuit component acts as a life support system for the cells – it has filtration for waste products, temperature control, gas mixing, and pumps to keep everything circulating."

In the lab, Cortical is assembling these units to construct a first-of-its-kind biological neural network server stack, housing 30 individual units that each contain the cells on their electrode array, which is expected to go online in the coming months.

The team aims to have four such stacks running and available for commercial use through a cloud system before the end of the year. The units themselves are expected to have a price tag of around US$35,000, to start with (anything close to this kind of tech is currently priced at €80,000, or nearly US$85,000).

An entire rack of CL1 units uses only around 850-1,000 W of energy, is fully programmable and offers "bi-directional stimulation and read interface, tailored to enable neural communication and network learning," the team noted in their launch release. Incredibly, the CL1 unit doesn't require an external computer to operate, either.

The complex, ever-evolving SBI neural networks – which, under a microscope, can be seen forming branches from electrode to electrode – have, to start with, the potential to revolutionize how drug discovery and disease modeling is researched.

“We’re aiming to be significantly more affordable, and we do want to bring that pricing down in the long-term, but that’s the much longer term,” Kagan said. “In the meantime, we provide access to people from anywhere, anyone, any house, through the cloud-based system.

"So even if you don’t have one of these [units]," he added, "you can access one of these from your home.”

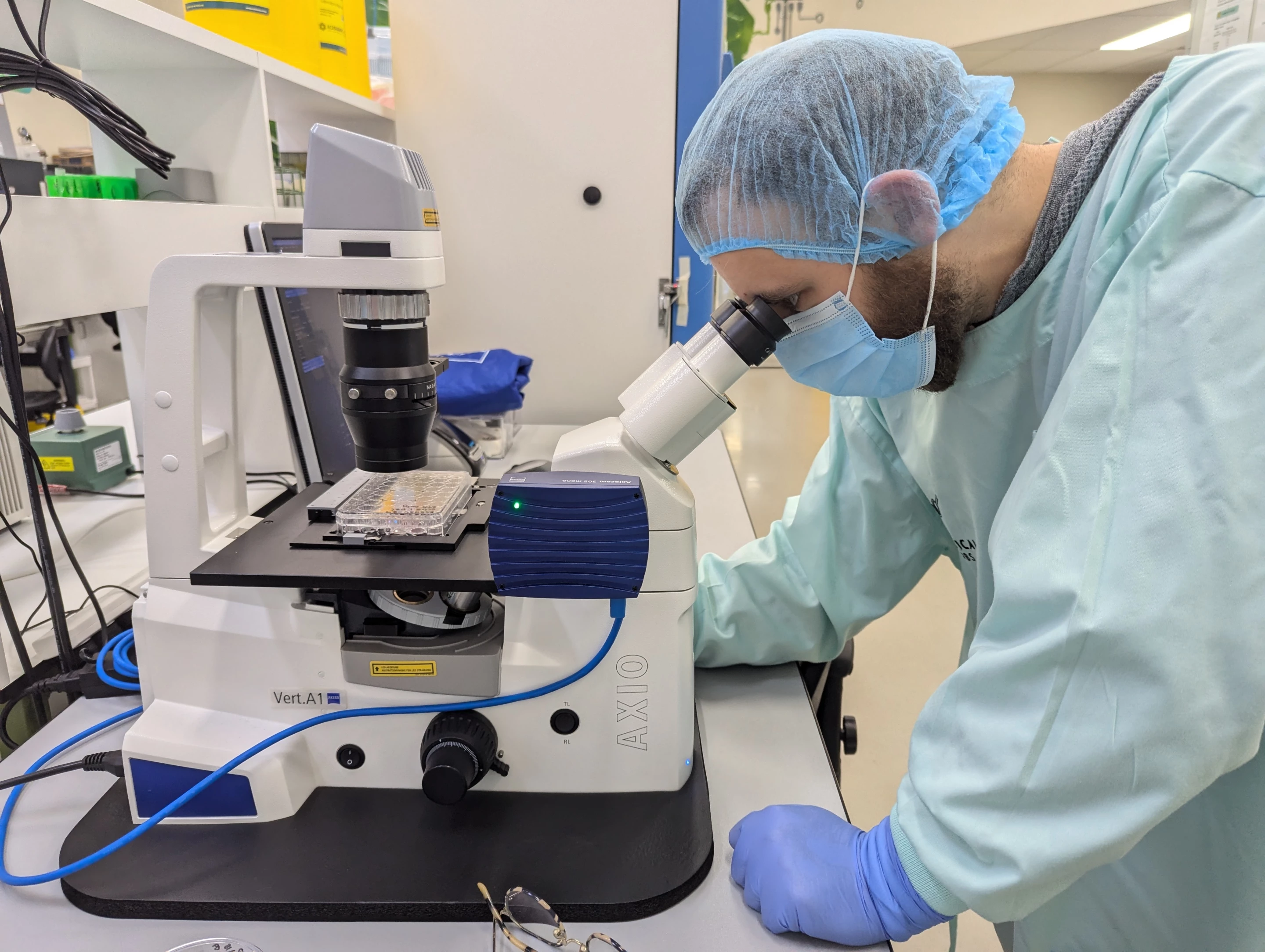

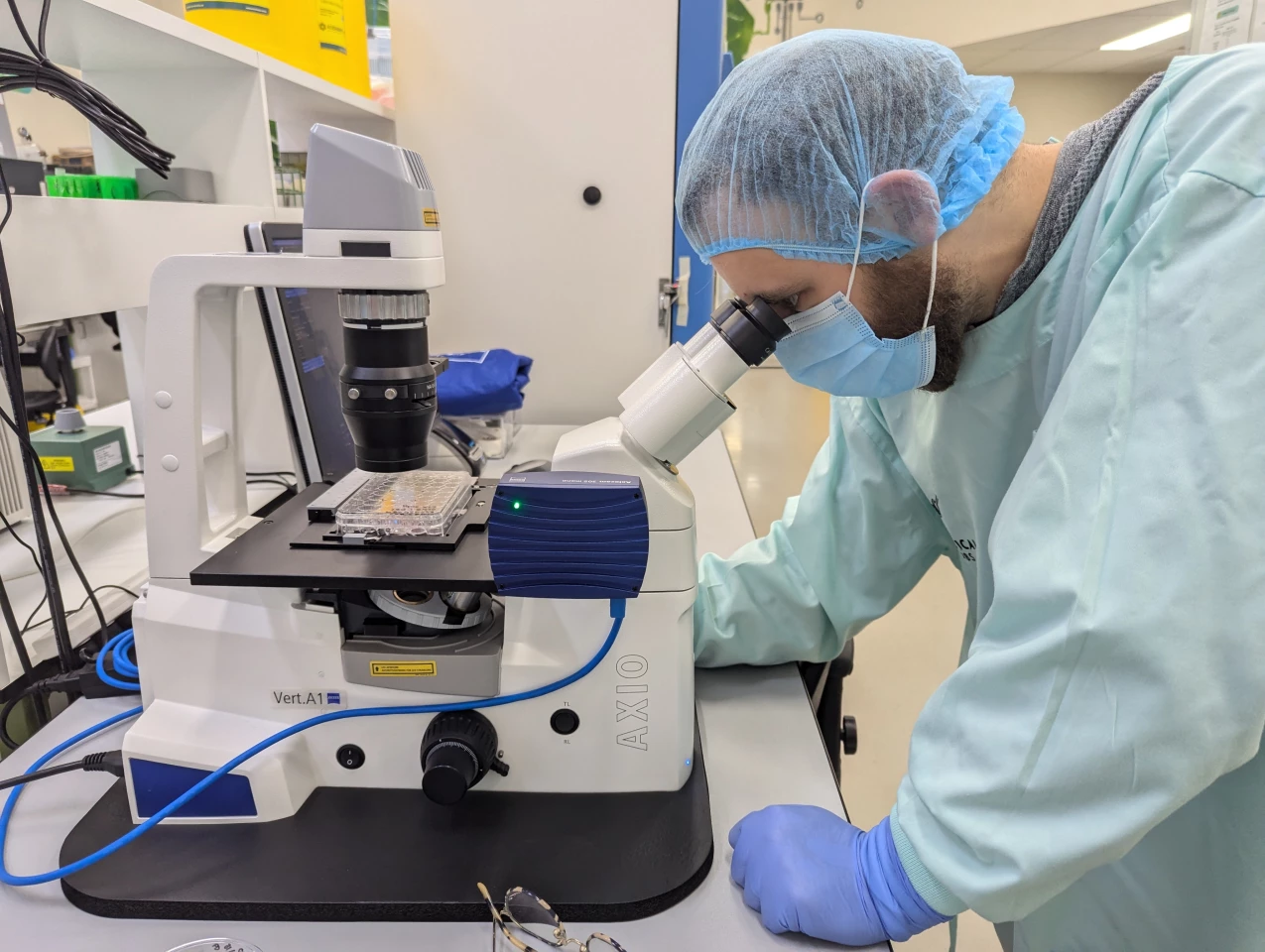

Taking us through the Physical Containment Level, or PC2, laboratory – a mix of computer hardware and more traditional biological specimens and equipment – Kagan showed us some of the all-important induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSC) under the microscope. IPSCs, cultivated in the lab from blood samples, are essentially blank slates that can grow into different types of cells.

“What we do is take those, and we start to use two different methods to differentiate them,” he explained. “One, we can either apply small molecules, which is called an ontogenetic differentiation protocol, where we essentially try to mimic the molecules that happen in utero or, rather, in the foetus’ developing brain. The other method is where we directly differentiate them, where we choose to up-regulate specific genes that are involved in neurons.”

One of the team's methods is quick and produces a high level of cellular purity, however, the downside is that it isn’t exactly representative of the human brain.

“The brain is not a high-purity organ; it has a lot of different cell types, a lot of different connections," Kagan said. "So if you only have one cell type, you might have that cell type, but you don’t have a brain."

The second method, “the small molecule approach,” produces diverse populations of cells, but it’s often unclear as to exactly what they're working with. And understanding this is critical to Cortical’s ambitious ongoing pursuit of building the Minimal Viable Brain. While the CL1 launch is the first step, the team is also hard at work on the next stage of SBI.

“You can categorize the main cells, but there’s always a lot of sub-cell types – and that’s really good, as we’ve found out, but we’d really like to have fully controlled direct differentiation,” he explains. “We just haven’t resolved that problem yet: What is the 'Minimal Viable Brain?'”

The MVB is an intriguing concept: How to bioengineer a human-like "brain" with the least amount of superfluous cell differentiation, but one that would have the complexity that growing a neural network made up of homogenous cell types doesn't have. This kind of tool would be a powerful model, allowing for even more control and nuanced analyses than what is currently possible in research conducted on a real brain.

“It would basically be the key biological components that allow something to process information in a dynamic and responsive way, according to underlying principles,” Kagan explained. “A single neuron can do a lot of stuff, and while it can respond to some degree of dynamic behavior, it can’t, for example, navigate an environment. The smallest working brains we know of have 301 or 302 – depending on who you ask – neurons, and that’s in the C. elegens. But each of those neurons are really highly specified.

“And another question is: Is the C. elegens brain the minimal viable brain? Do you need all of those neurons or could you achieve it with, you know, 30 neurons that are all uniquely circuited up?” he continued. (The organism is, of course, the science world's favorite nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans.) “And if that’s the case, can you build a more complex network of those with 100,000 of the same 30? We don’t know the answer to any of this yet, but with this technology we can uncover it.

“We’re starting to add more and more cell types to this culture as we go, but one thing that’s holding us back is the tools,” he said. “The [CL1] unit didn’t exist until we built it, and you need a tool like that to answer questions like, ‘What is the minimal viable brain?'" If you have 120 units, you can set up really well-controlled experiments to understand exactly what drives the appearance of intelligence. You can break things down to the transcriptomic and genetic level to understand what genes and what proteins is actually driving one to learn and another not to learn. And when you have all those units, you can immediately start to take the drug discovery and disease modeling approach.”

This is particularly important for research into better treatments or even cures for conditions such as epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease, and other brain-related illnesses. In the meantime, the CL1 system, is expected to advance research into diseases and therapeutics considerably.

“The large majority of drugs for neurological and psychiatric diseases that enter clinical trial testing fail, because there’s so much more nuance when it comes to the brain – but you can actually see that nuance when you test with these tools," he explained. “Our hope is that we’re able to replace significant areas of animal testing with this. Animal testing is unfortunately still necessary, but I think there are a lot of cases where it can be replaced and that’s an ethically good thing."

The ethics of this technology has been front and center for Cortical – that breakthrough 2022 paper sparked plenty of debate around it, particularly in the area of human "consciousness" and "sentience." However, guardrails are in place, as much as they can be, for the ethical use of the CL1 units and the remote WaaS access.

"There are numerous regulatory approvals required, based on location and specific use cases," the team noted in its launch statement. "Regulatory bodies may include health agencies, bioethics committees, and governmental organisations overseeing biotechnology or medical devices. Compliance with these regulations is essential to ensure responsible and ethical use of biological computing technologies."

But as a global frontrunner in this ambitious technology, Cortical knows that – much like the rapid advancement of non-biological AI – it's not easy to predict the broad applications of SBI. And one other challenge the company faces is funding – something that the realization of CL1 as a tangible, usable technology might change.

“The difficulty I keep hearing [from investors] is that we don't fit into a box,” Kagan told us, as we took off our lab coats, hair nets and masks, and relocated to a couch by the computer room upstairs. “And we don’t – we’re a technology that crosses a number of different boundaries. If you look at the priority sectors, we can cover everything from the enabling capabilities of biotechnology, robotics, medical science, and a range of other things. We’re not quite AI, we’re not quite medicine – we can do both AI and medicine, but we’re not either. So we often get excluded."

As such, the launch of the physical CL1 system and the Cortical Cloud for WaaS remote use is a huge achievement, with Kagan and team excited to see where SBI can go once its in people's hands.

"The CL1 is the first commercialized biological computer, uniquely designed to optimize communication and information processing with in vitro neural cultures," the team noted. "The CL1, with built-in life support to maintain the health of the cells, holds significant possibilities in the fields of medical science and technology.

"SBI is inherently more natural than AI, as it utilizes the same biological material – neurons – that underpin intelligence in living organisms," Cortical added. "By leveraging neurons as a computational substrate, SBI has the potential to create systems that exhibit more organic and natural forms of intelligence compared to traditional silicon-based AI."

Source: Cortical Labs