A new study has found the non-invasive application of in-ear electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve to be safe and effective in reducing osteoarthritis-related knee pain. It opens the door to innovative, quality-of-life-improving treatment.

The vagus nerve is key to the parasympathetic nervous system, which produces the calming "rest and digest" response, in opposition to the sympathetic nervous system’s "fight or flight" response. The nerve is like a superhighway, connecting the brain to other organs such as the heart, lungs, and digestive system. It’s also involved in managing pain signals.

In a new study led by the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), researchers conducted a pilot trial to evaluate the effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation via the ear to treat osteoarthritis (OA)-related knee pain. It’s the first study to do so.

“As a physical therapist, I saw many patients suffering from OA knee pain,” said lead author Kosaku Aoyagi, PhD, an assistant professor of physical therapy and movement sciences in UTEP’s College of Health Sciences. “This motivated me to pursue research to improve their quality of life, and our results showed strong potential.”

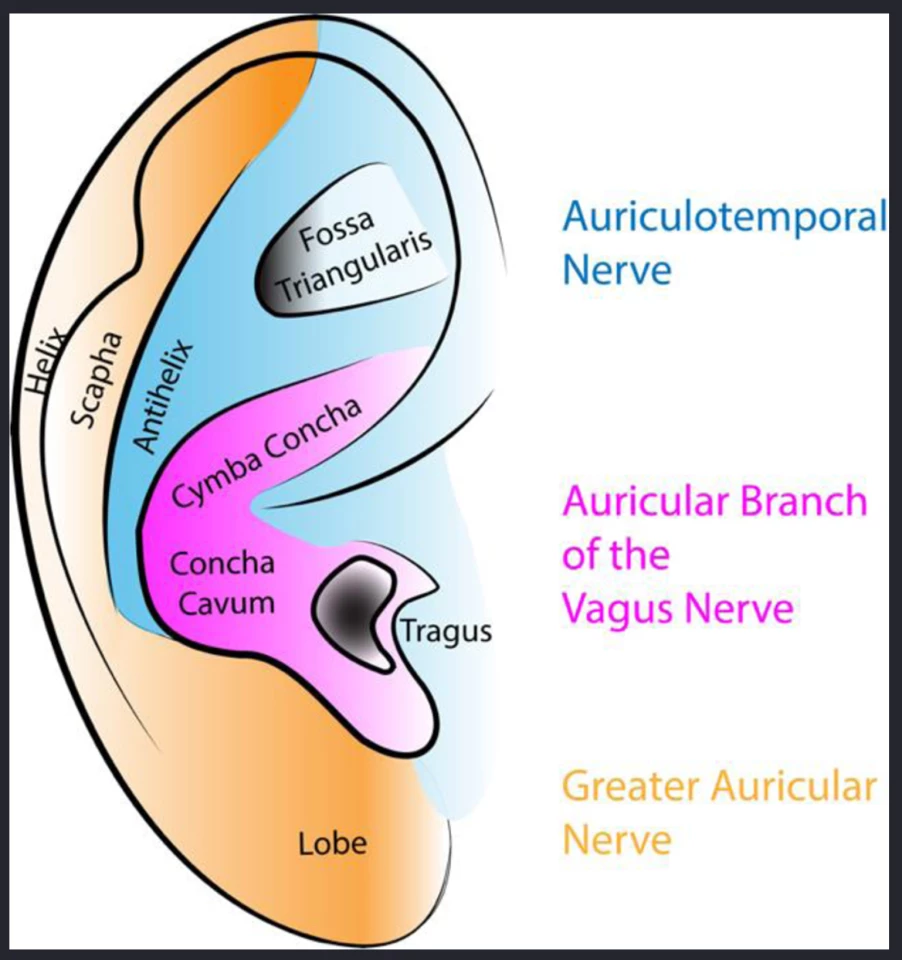

Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS), where a mild electrical current is applied to the nerve, usually through the skin behind the ear, has been used previously to treat indigestion, pain, and even to slow aging. tVNS is a safe, non-invasive intervention that has been shown to reliably improve parasympathetic function. It can be delivered using a device that sits on the ear and sends an electrical pulse to the auricular branch of the vagus nerve, which is found under the skin in the magenta area in the diagram below.

“The current evidence suggests that individuals with OA knee pain have an imbalance of sympathetic versus parasympathetic activity in the body, which can cause pain,” Aoyagi said. “By stimulating the vagus nerve, we hypothesized that our treatment may rectify this imbalance.”

The researchers recruited 30 adults with knee OA and activity-related knee pain and gave each of them a 60-minute auricular tVNS treatment. Participants were asked not to take pain medications 24 hours before their study visit and knee pain was assessed before treatment, immediately after, and 15 minutes afterwards. Baseline average knee pain was scored at 3.1 on a zero-to-10-point pain scale.

Eleven out of the 30 participants (37%) exceeded the minimal clinically important improvement in pain after tVNS. Compared to baseline, knee pain was reduced by 1.27 points immediately after treatment, and by 1.87 points 15 minutes after.

“All of our participants completed the full 60-min tVNS protocol without any major side effects and >one-third exceeded the minimally clinically important threshold for knee pain improvement,” the researchers said. “This suggests that improvement of their symptoms might be derived from improvement of parasympathetic function and/or central pain mechanisms because no local intervention to the knee was applied.”

The researchers acknowledge that their lack of a control group means that the effect they observed might be due to the placebo effect. They also considered, as a limitation, that lying or sitting down quietly for an hour as part of the treatment may, by itself, have had an effect on pain. Additionally, they only looked at the effect of one treatment, and their study population was predominantly Hispanic, which limits the generalizability of the findings.

“However, despite these limitations, our novel preliminary data have shown promising signals of the safety, feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of tVNS for symptoms of knee OA and support the promise of a larger study with multiple tVNS sessions, the addition of a control group, and controlling of potential confounders in diverse samples to develop tVNS as an effective and safe pain-relieving treatment for people with knee OA.”

The study was published in the journal Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Open.

Source: UTEP