A subtle tweak in the way you walk – putting your toes in or out by a few degrees – could ease knee osteoarthritis pain and slow joint damage, according to new research that found personalized gait retraining can reduce strain on vulnerable cartilage.

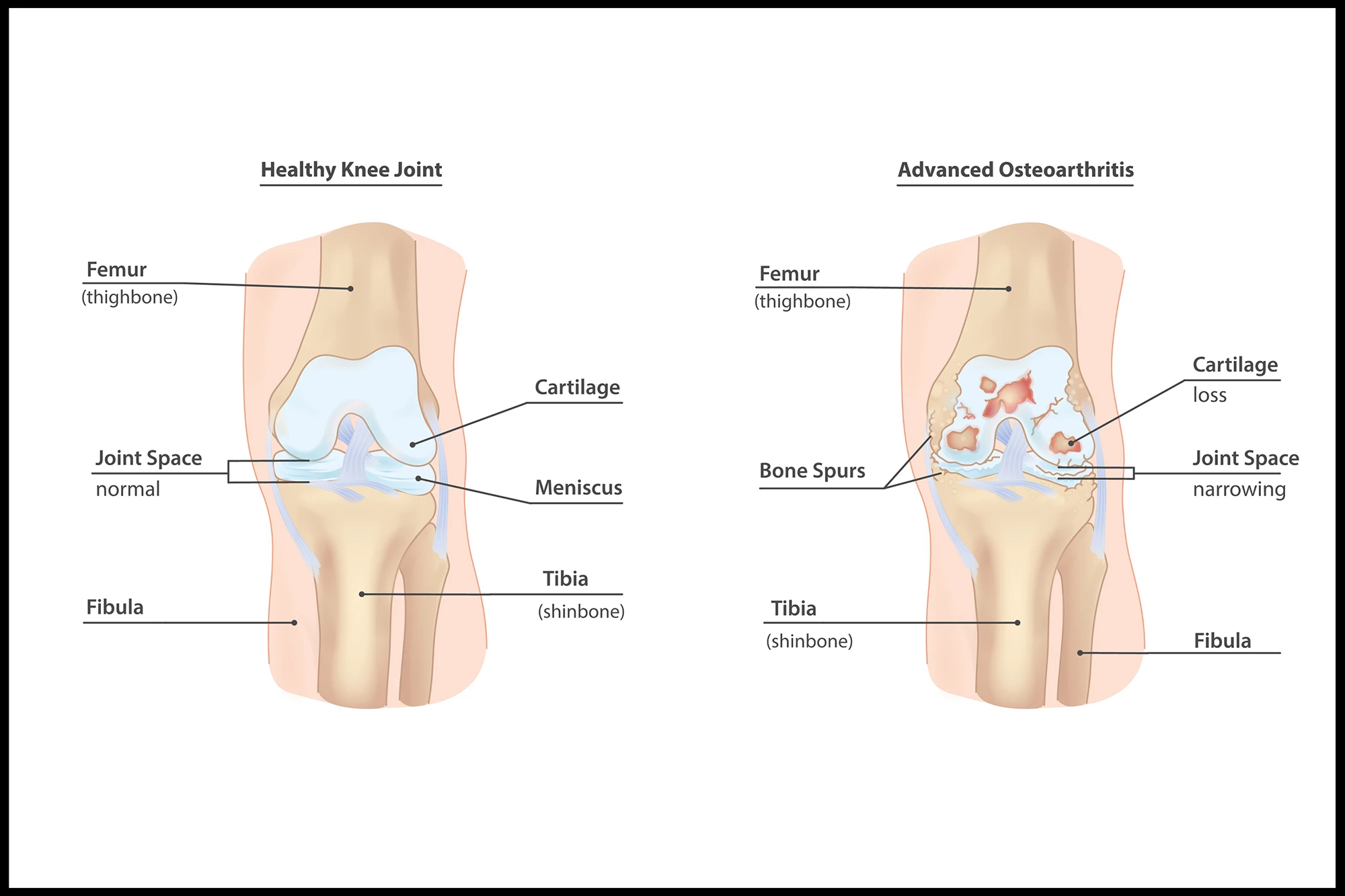

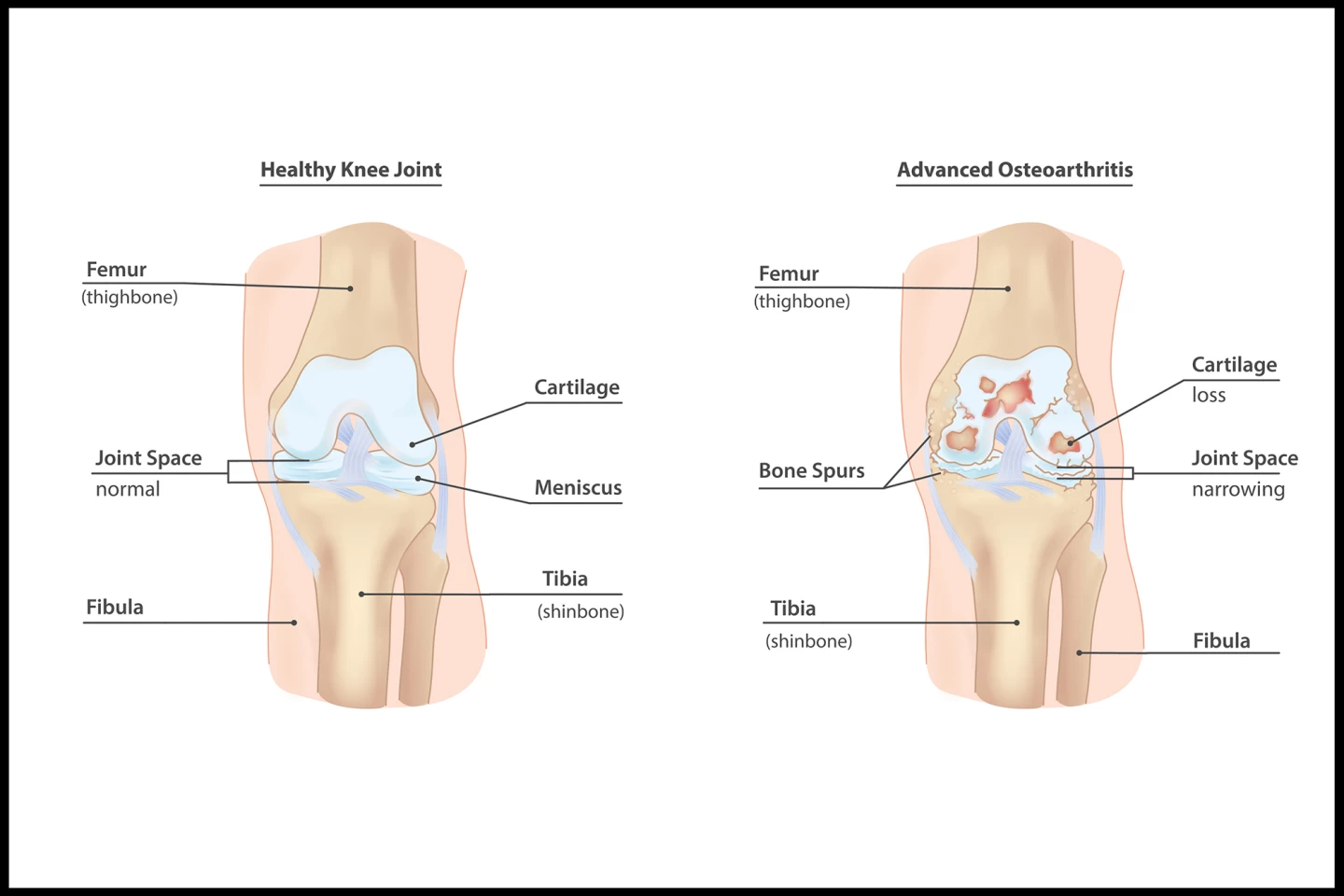

The inner, or medial, part of the knee joint is the most common site where cartilage breaks down in osteoarthritis (OA), causing pain, stiffness, and limited movement. Unfortunately, the simple act of walking increases loading on the joint, which accelerates the disease’s progression. We’ve previously reported on scientifically backed non-drug methods for treating OA knee pain.

Now, a new study has found that another non-invasive, non-drug treatment, making a small change to the way a person walks, may ease pain and help slow OA’s progression by reducing joint loading.

“Although our results will have to be confirmed in future studies, they raise [the] possibility that the new, noninvasive treatment could help delay surgery,” said co-lead author Valentina Mazzoli, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Radiology at NYU’s Grossman School of Medicine. “Altogether, our findings suggest that helping patients find their best foot angle to reduce stress on their knees may offer an easy and fairly inexpensive way to address early-stage osteoarthritis.”

The researchers recruited 68 adults, with a mean age of 64, who had confirmed medial knee OA. To be included, the participants also had to have medial knee pain of three points or greater on an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS), be able to walk safely on a treadmill without an aid for 25 minutes and have a BMI of less than 35 kg/m2 (obesity is defined as a BMI of 30 or more). Importantly, the included participants had to already be able to reduce knee joint loading during a screening gait test.

Half of the participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group; the other half received a sham treatment. In the intervention group, participants adopted one of four new foot positions – toe-in or toe-out by either five degrees or 10 degrees – determined using computer simulations to most reduce joint loading. The sham group practiced walking using their natural foot angle. All of the participants underwent six-weekly gait lab sessions with real-time feedback, plus daily walking practice at home. The researchers measured knee pain, knee loading, and cartilage microstructure (using MRI scanning) at regular intervals over 12 months.

After one year, compared with the sham group, the intervention group saw a number of improvements. They reported 1.2 points greater pain reduction, a meaningful difference that was similar to the effect of taking over-the-counter pain medication. They had a 7.5% greater reduction in knee adduction moment, a measure of joint load. And their medial knee cartilage showed less worsening, suggesting slower cartilage degeneration. At least a one-point pain reduction was achieved by 91% of those in the intervention group, versus 66% of sham participants. No severe adverse events were reported, although a few participants dropped out due to increased knee pain (two in the intervention group; one in the sham group).

“These results highlight the importance of personalizing treatment instead of taking a one-size-fits-all approach to osteoarthritis,” Mazzoli said. “While this strategy may sound challenging, recent advances in detecting the motion of different body parts using artificial intelligence may make it easier and faster than ever before.”

While in the present study the researchers used a specialized lab to measure gait, AI software that estimates joint loading using smartphone videos is available and can allow clinicians to perform gait analysis in their clinic without this expensive equipment.

The study had some limitations. Principally, the researchers delivering training knew group allocations, and pain ratings were collected by unmasked staff, which could lead to possible bias. Additionally, participants weren’t tested at the end of the study to see if they guessed their group. There were fewer participants than planned, and some data were missing due to the COVID-19 pandemic-related shutdown. The study excluded people with severe obesity or advanced OA, so results may not apply to those groups. And, follow-up was limited to 12 months, so it’s unclear if the benefits last long term.

Nonetheless, the study demonstrates a potential new treatment for OA. Personalized gait retraining could be a safe, non-surgical option to reduce pain and possibly slow disease in some patients. It’s one of those “there’s no harm in trying”-type treatments that could be used alongside exercise and pain management, avoiding the side effects of long-term medication use.

The study was published in the journal The Lancet Rheumatology.

Source: NYU Langone Health