As soon as there were drones, there were visions of drone deliveries. Robotic insects bringing parcels and pizzas to your front or back doorstep in a jiffy, not waiting for traffic lights and traveling as the crow flies. But as aviation regulators around the world work with the likes of Amazon, UPS and DHL to clear a legal pathway for these kinds of services to begin, a new study out of Germany points out that the high energy cost of flying drones could make them worse for the environment than vans.

Multicopter drones are a marvelous technology, but as aircraft, they're highly inefficient. Lacking wings, which can develop lift by moving forward through air, drones must constantly provide upward thrust just to keep themselves airborne. Add the weight of your grande burrito delivery, and they've got to pull even harder, and energy consumption goes up considerably when they've got to fly into a headwind or crosswind. Not to mention, they can only carry one parcel at a time, making every trip a round trip of its own.

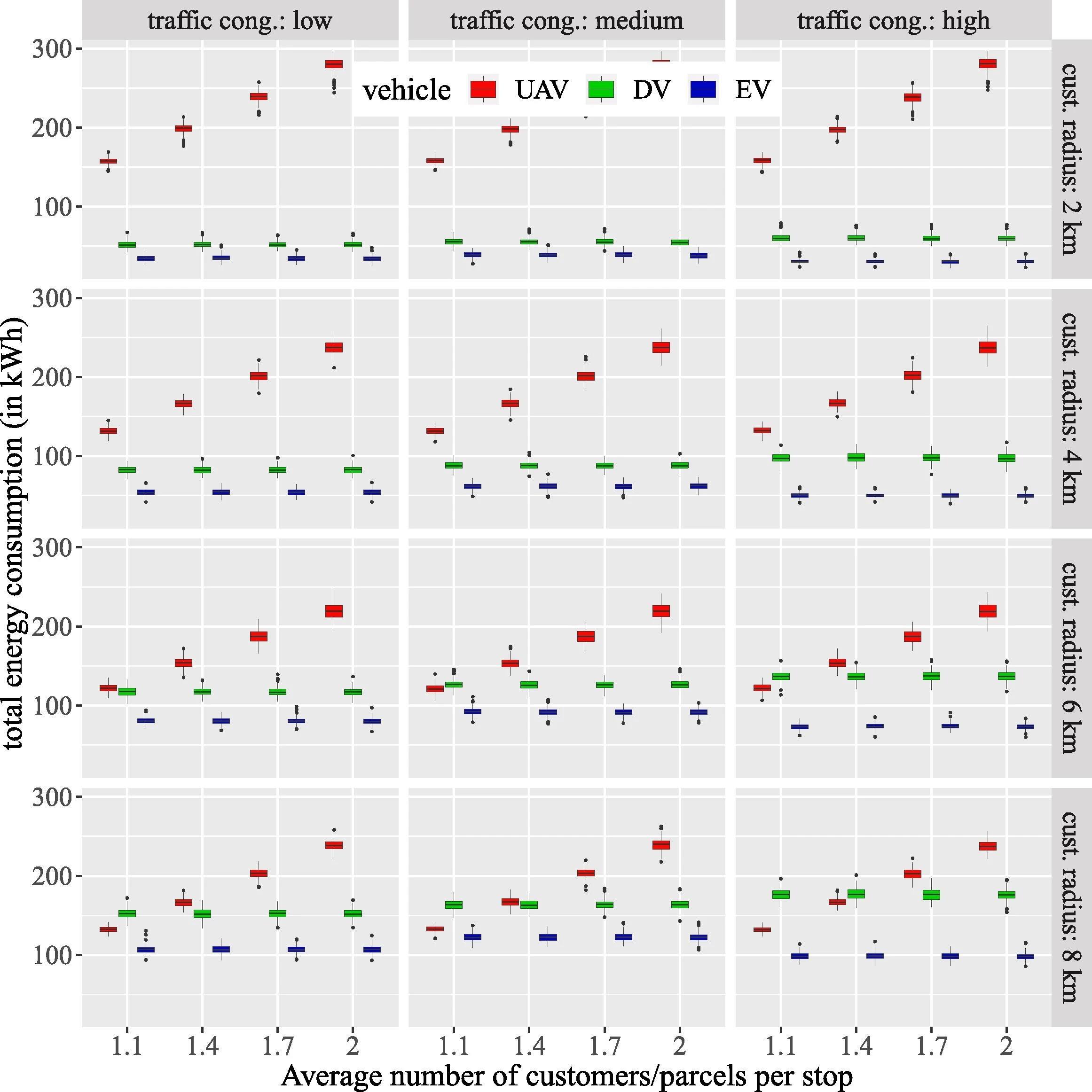

Researchers from the Martin Luther Universitat in Halle-Wittenberg have run the calculations on urban and rural deliveries, comparing drones against diesel and electric vans, and made some surprising discoveries. Based on simulations run on Berlin and the surrounding areas, the researchers found that in dense urban areas, electric vans are by far the most energy-efficient delivery option. Diesel vans use around five times more energy in this situation, and drones use around 10 times as much .

Population density is the key factor here; vans can carry literally hundreds of items at a time, and when delivery routes are short and packed with lots of drop-offs, minimal energy is wasted. The figures above assume that the vans are carrying 100 parcels each, and that all parcels weigh 2.5 kg (5.5 lb), among other things.

Interestingly, once you move into sparse rural areas, the drones begin to even things up. With significantly further to travel between stops, the vans lose most of their energy advantages. When customers are up to 8 km (5 mi) away from the delivery center and wind conditions are ideal, drones become more efficient than diesel vans for single deliveries.

Naturally, energy usage isn't the only thing to consider; there's the cost of staffing, the fact that electricity generation creates less pollution than diesel automobiles, driver pay rates, maintenance, downtime for battery charging and many other factors. But on a purely environmental analysis it seems electric vans are by far the best solution for getting a lot of things to a lot of tightly packed places, efficiently and quickly.

The study is available on Science Direct.

Source: Martin Luther Universitat