Researchers have used a low-emissions method to harvest hydrogen and graphene from waste plastics. They say it not only solves environmental problems like plastic pollution and greenhouse gas production, but the value of the graphene by-product could offset the costs of producing hydrogen.

Hydrogen is used to power vehicles, generate electricity, and heat our homes and businesses. Hydrogen contains more energy per unit of weight than fossil fuels, which is important from an environmental standpoint as the main cause of global greenhouse gas emissions is the release of carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels.

More than 95% of hydrogen is synthesized through steam-methane reforming, which produces 11 tonnes (12 tons) of carbon dioxide for every tonne of hydrogen, the vast majority of which is gray hydrogen. By comparison, “green hydrogen” produced using renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, or hydropower to split water into its component elements, is expensive, costing around US$5 for just over two pounds (around one kilogram).

Researchers from Rice University have now developed a means of harvesting valuable hydrogen and graphene from waste plastic using a low-emissions, catalyst-free method that has the potential to pay for itself.

“In this work, we converted waste plastics – including mixed waste plastics that don’t have to be sorted by type or washed – into high-yield hydrogen gas and high-value graphene,” said Kevin Wyss, lead author of the study. “If the produced graphene is sold at only 5% of current market value – a 95% off sale! – clean hydrogen could be produced for free.”

In steam-methane reforming, high-temperature steam (1,292 °F to 1,832 °F/700 °C to 1,000 °C) is used to produce hydrogen from a methane source such as natural gas. Methane reacts with the steam in the presence of a catalyst to produce hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide.

“The main form of hydrogen used today is ‘gray’ hydrogen, which is produced through steam-methane reforming, a method that generates a lot of carbon dioxide,” said James Tour, one of the study’s corresponding authors. “Demand for hydrogen will likely skyrocket over the next few decades, so we can’t keep making it the same way we have up until now if we’re serious about reaching net zero emissions by 2050.”

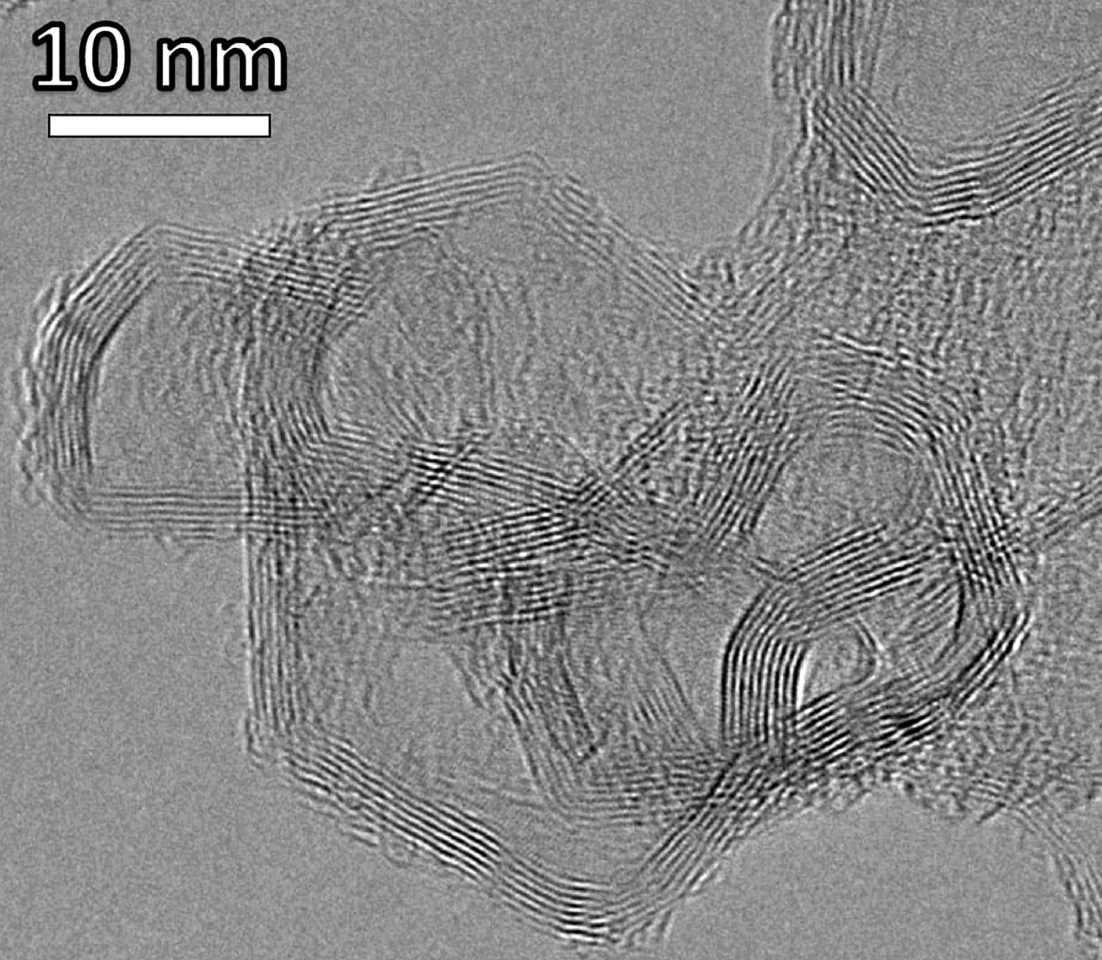

Waste plastics hang around in the environment for ages, threatening wildlife and spreading toxins to animals and humans. In the current study, the researchers exposed plastic waste to rapid flash Joule heating for about four seconds. Raising the temperature up to 3,100 kelvin vaporizes the hydrogen present in the plastic, leaving behind graphene, a light, durable material comprised of a single layer of carbon atoms. Graphene is used in electronics, energy storage, sensors, coatings, composites, and biomedical devices, to name but a few of its applications.

“When we first discovered flash Joule heating and applied it to upcycle waste plastic into graphene, we observed a lot of volatile gases being produced and shooting out of the reactor,” Wyss said. “We wondered what they were, suspecting a mix of small hydrocarbons and hydrogen, but lacked the instrumentation to study their exact composition.”

After acquiring the equipment needed to analyze the vaporized contents thanks to funding from the US Army Corps of Engineers, the researchers found their suspicions were correct: the process produced hydrogen gas.

“We know that polyethylene, for example, is made of 86% carbon and 14% hydrogen, and we demonstrated that we are able to recover up to 68% of that atomic hydrogen as gas with a 94% purity,” said Wyss. “Developing the methods and expertise to characterize and quantify all the gases, including hydrogen, produced by this method was a difficult but rewarding process for me.”

The researchers say that based on life-cycle assessment, their method produces less emissions than other hydrogen production methods. Life-cycle assessment is a technique used to analyze the holistic environmental impacts and resource demands associated with production methods.

“The flash H2 process provides improvements in both cumulative energy demand (33-95% less energy) and greenhouse gas emissions (65-89% less emissions) when compared to other waste plastic or biomass deconstruction methods for H2 production,” said the researchers.

The researchers say that a benefit of their flash Joule heating process is that the waste plastic doesn’t need to be washed or separated and can be leveraged to produce negative-cost clean hydrogen from waste materials.

They plan to increase their understanding of the flash Joule heating mechanism to improve its scalability and optimize hydrogen production.

“I hope that this work will allow for the production of clean hydrogen from waste plastics, possibly solving major environmental problems like plastic pollution and the greenhouse gas-intensive production of hydrogen by steam-methane reforming,” said Wyss.

The study was published in the journal Advanced Materials.

Source: Rice University