Devices that mimic the natural process of photosynthesis, in which plants use sunlight to turn water and carbon dioxide into energy, could one day help us tackle a number of environmental issues. Scientists have now demonstrated a new type of technology that can not only replicate this process to produce clean hydrogen fuel, but undergo morphological changes during use that makes it become more efficient over time.

The research was carried out by scientists at the University of Michigan (UM) and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who were working with an artificial photosynthesis device previously developed by UM engineer Zetian Mi. The device promised a cleaner form of hydrogen production, which typically involves using natural gas or electrical energy, by instead harnessing sunlight to split fresh and salt water and generate hydrogen for use in fuel cells.

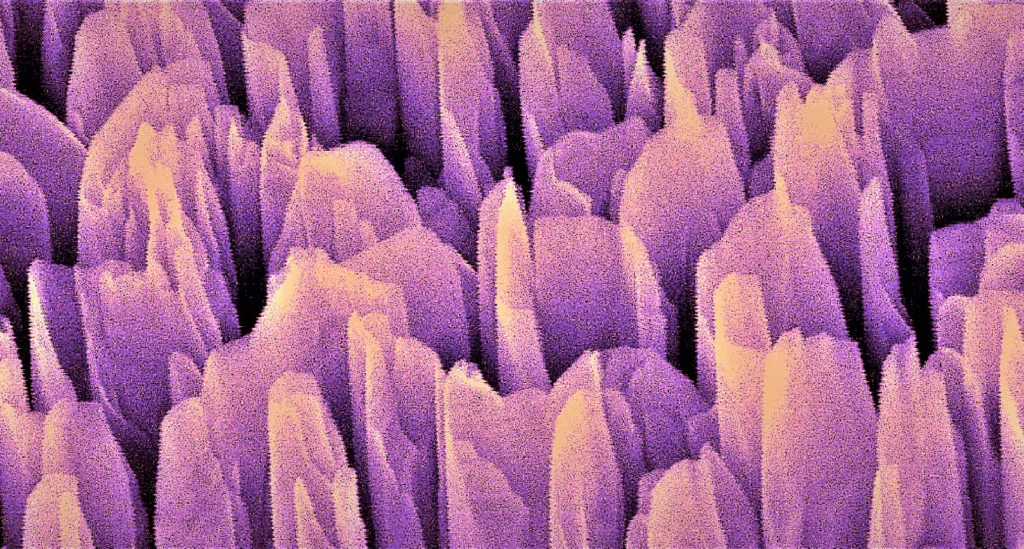

Built from silicon and gallium nitride, materials commonly used in electronics and solar cells, the device offered an impressive three-percent solar-to-hydrogen efficiency, compared to the one-percent efficiency offered by previous devices. It achieved this through a "cityscape" of gallium nitride towers on a silicon backing that turned sunlight into free electrons, which in turn split the water into hydrogen and oxygen.

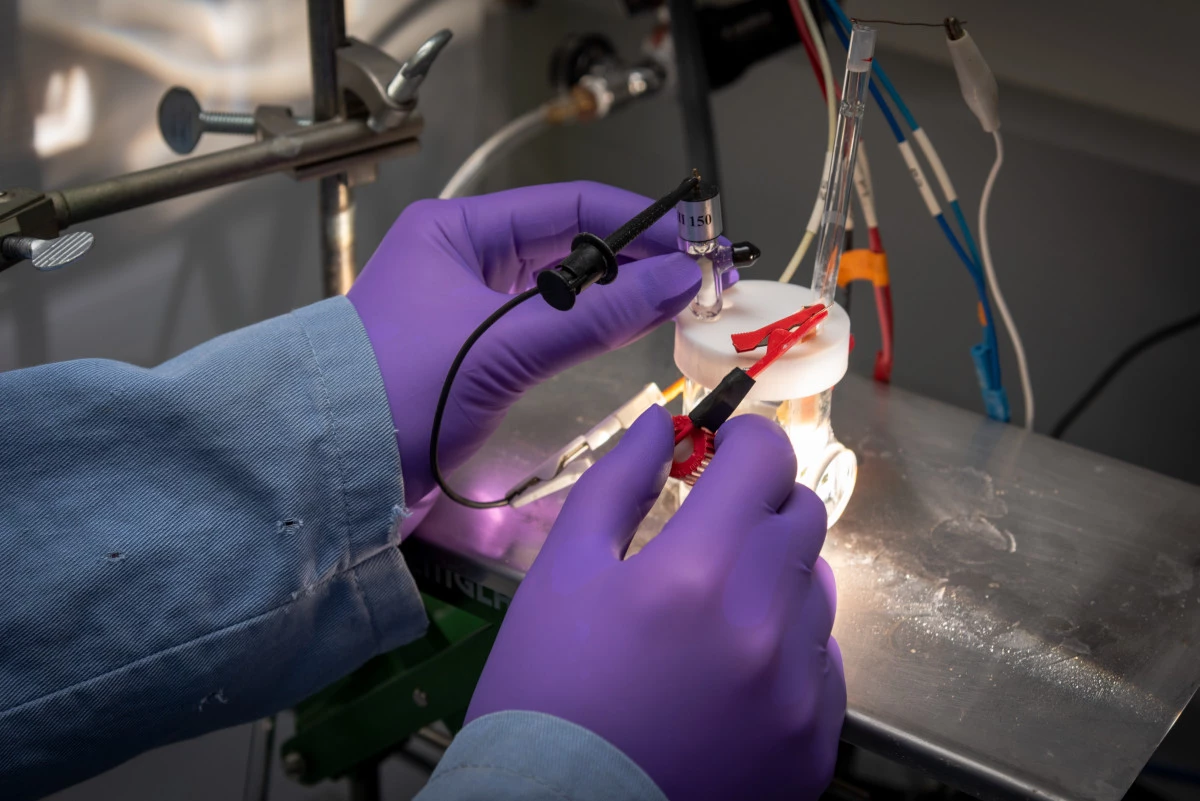

These results were published back in 2018, but the scientists have continued studying the device to better understand the reasons behind its superior efficiency. In the latest study, the team used a range of advanced microscopy and spectroscopy techniques to observe the materials in action, and uncovered some surprises.

While an artificial photosynthesis device would normally be expected to decline in performance in a matter of hours as the materials wear out, this one actually grew more efficient over time. The scientists' observations revealed that as the system was used, the very tops of the gallium nitride towers formed new sites for hydrogen production by absorbing oxygen and taking on new properties, becoming a material known as gallium oxynitride.

“We discovered an unusual property in the material that enables it to become more efficient and stable,” says Francesca Toma, senior author of the paper. “Our discovery is a real game-changer. I’ve never seen such stability.”

For their next steps, the scientists will experiment with the material as part of a complete photoelectrochemical cell for splitting water, which will include exploring how similar materials might make these systems even more stable.

“The collaboration helped to identify the fundamental mechanisms behind why this material gets more robust and efficient instead of degrading," says Mi. "The findings from this work will help us design and build more efficient artificial photosynthesis devices at a lower cost.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Materials.

Source: University of Michigan