For nearly a century, a strange band of thousands of holes carved into a Peruvian hillside has defied explanation. Stretching for nearly a mile (1.5 km) along the edge of the Pisco Valley, Monte Sierpe – "serpent mountain" appears to be a deliberate, repetitive and almost mathematical feature – but its real purpose has so far eluded scientists.

Now, researchers from the University of Sydney believe they have cracked the code of the so-called "Band of Holes," with a far more human explanation than previously thought. In fact, the archeologists have found new clues that point to the mysterious stretch of holed-out ground as being some kind of indigenous trade and accounting system that had been built into the landscape and primarily used during the Late Intermediate Period, which in this region spans roughly 1000-1450 CE, probably around the 14th century.

“Why would ancient peoples make over 5000 holes in the foothills of southern Peru?" said Dr Jacob Bongers, lead author and digital archeologist at the University of Sydney. "Were they gardens? Did they capture water? Did they have an agricultural function? We don’t know why they are here, but we have produced some promising new data that yield important clues and support novel theories about the site’s use.

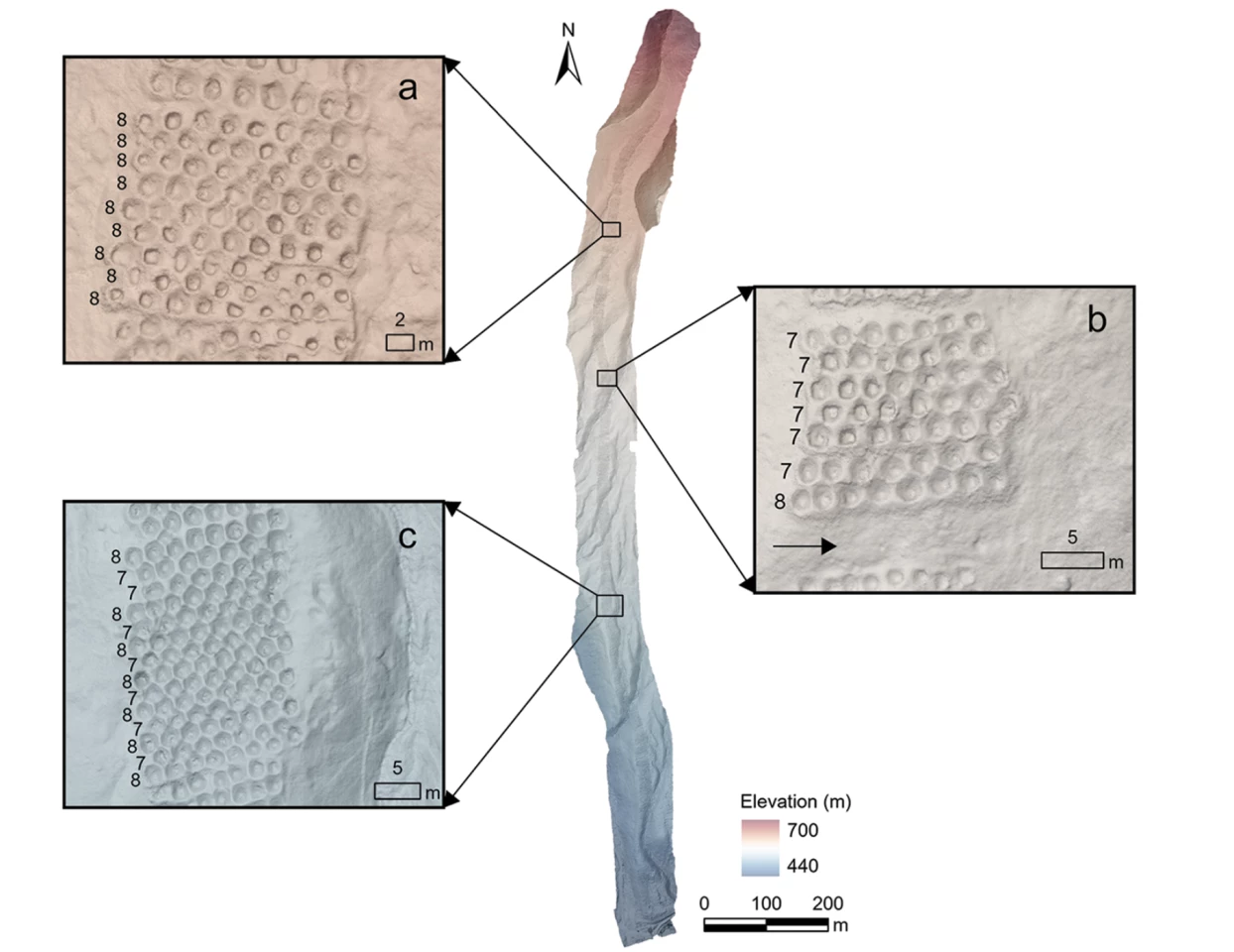

Using drones to map the site in unprecedented detail, the researchers found numerical patterns in the placement, hinting at a hidden functionality beyond aesthetics. They also discovered that Monte Sierpe is similar to the structure of at least one Inca khipu (an ancient knotted-string accounting device) that was recovered from the same valley.

“This is an extraordinary discovery that expands understandings about the origins and diversity of indigenous accounting practices within and beyond the Andes,” Bongers said.

Monte Sierpe is made up of around 5,200 shallow pits, measuring 1 to 2 m (3 to 6.5 ft) wide and 0.5 to 1 m (1.5 to 3 ft) deep, arranged into neat blocks along a narrow ridge. Each pit is roughly the size of a small storage cavity, and while the band appears continuous when sighted from a distance, closer inspection reveals that it is broken into sections, separated by gaps that allow foot traffic across the mountain. What's more, rows of holes consistently repeat the same pattern, sometimes alternating between specific numbers. Some sections contain long stretches of identical rows, while others show repeating alternations. The structure, the team argues, resembles khipus – except on at a large scale, and built into earth and stone.

Hole soil analysis also found ancient pollens of maize – a key staple in the Andes – and reeds traditionally used for basket-making. In addition to this, there were traces of squash, amaranth, cotton, chili peppers and other crops that haven't been farmed on the arid land where Monte Sierpe sits. Because many of these plants produce little airborne pollen, it's unlikely they settled in the holes naturally. Instead, the researchers believe, people carried goods to the site and deposited them in the holes, likely using baskets or bundled plant fibers that were periodically replaced.

“This is very intriguing,” Bongers said. “Perhaps this was a pre-Inca marketplace, like a flea market. We know the pre-Hispanic population here was around 100,000 people. Perhaps mobile traders (seafaring merchants and llama caravans), specialists (farmers and fisherfolk), and others were coming together at the site to exchange local goods such as corn and cotton. Fundamentally, I view these holes as a type of social technology that brought people together, and later became a large-scale accounting system under the Inca Empire."

Radiocarbon dating places active use of the site in the 14th century, during the Late Intermediate Period, when the Chincha Kingdom dominated the region. Historical records describe the Chincha as skilled traders, operating networks along the coast and inland long before the arrival of the Inca. Monte Sierpe sits at a strategic crossroads between ecological zones and major pre-Hispanic roads, making it an ideal meeting point for bartering.

“There are still many more questions," Bongers says. "Why is this monument only seen here and not all over the Andes? Was Monte Sierpe a sort of ‘landscape khipu’? – but we are getting closer to understanding this mysterious site. It is very exciting.”

The researchers argue that the holes weren't storage silos in the modern sense, but markers of equivalence – a way to make quantities visible and negotiable in a society without currency. Seeing rows of filled pits would have allowed people to assess supply at a glance. Later, with the arrival of the Inca, the same infrastructure may have been repurposed. The empire relied heavily on accounting systems to manage labor, and the segmented, numerical layout of the Band of Holes would have lent itself to tracking these sorts of transactions.

The Band of Holes garnered the attention of researchers in 1933, after aerial photos published in National Geographic sparked curiosity – and while the latest study can't confirm beyond a doubt, it provides the strongest evidence yet in Monte Sierpe's origin story.

“Hypotheses regarding Monte Sierpe’s purpose range from defense, storage, and accounting to water collection, fog capture and gardening, yet the true function of the site remains unclear,” said Dr Bongers. “This research contributes an important Andean case study on how past communities modified landscapes to bring people together and promote interaction."

The research was published in the journal Antiquity.

Source: University of Sydney