A nuclear production facility in Washington state, called the Hanford site, once forged the plutonium that reshaped the world. Now it’s forging glass; a quiet act of undoing at one of Earth’s most contaminated sites.

Eighty years ago, at the height of World War II, the Hanford site forged the plutonium that would help end the war and usher in a new atomic era. Now the site is forging glass, each glowing canister a quiet reversal of that legacy. After years of anticipation, the US Department of Energy (DOE) has finally begun vitrifying Hanford’s nuclear waste, sealing it forever inside glass logs that mark the first real progress in cleaning one of Earth’s most contaminated nuclear sites.

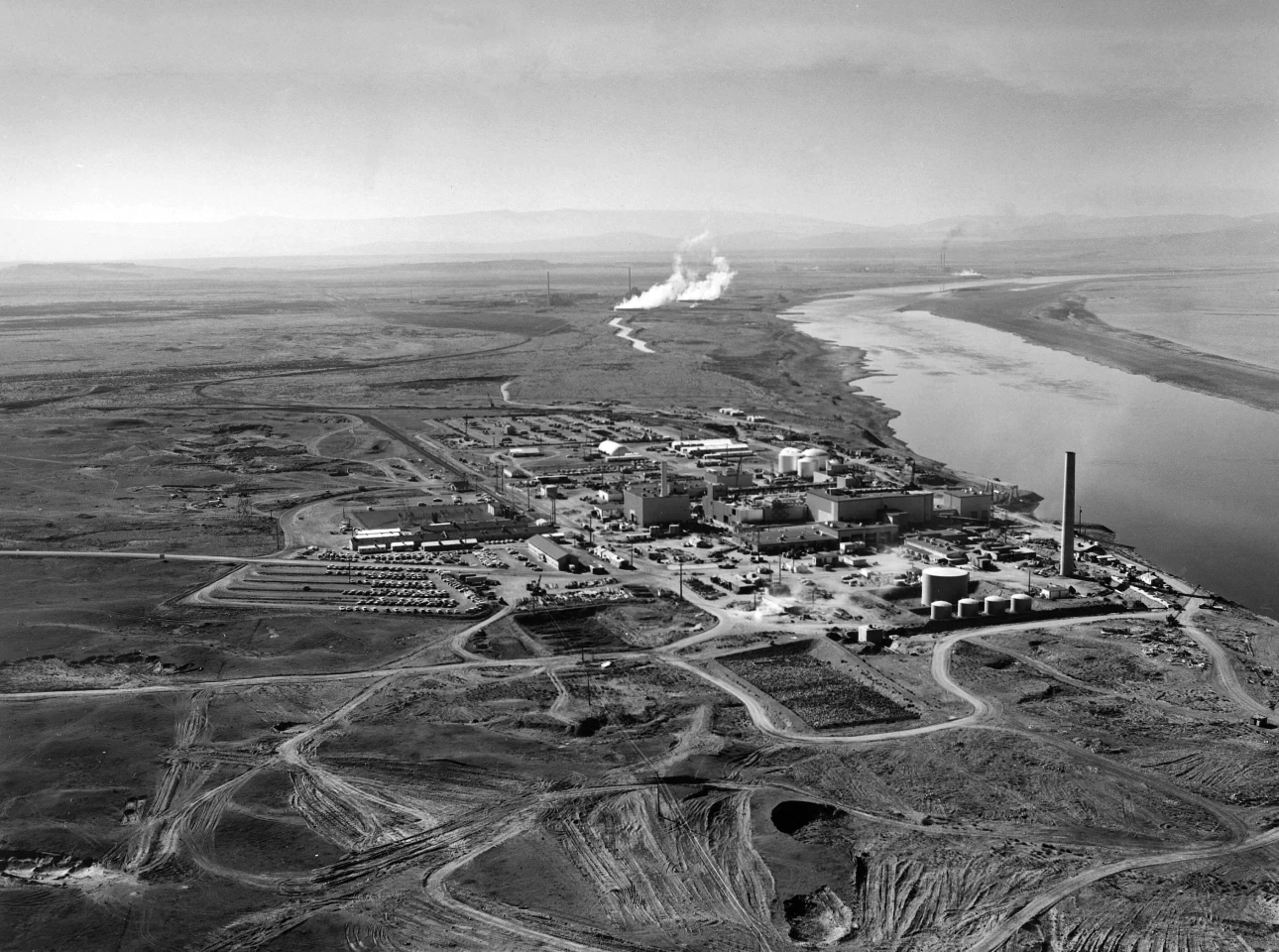

During World War II and throughout the Cold War, the Hanford reactors along the Columbia River near Richland, Washington produced most of the plutonium in the US arsenal of bombs and missiles, leaving behind 56 million gallons of radioactive sludge stored in 177 aging underground tanks. For decades the waste lingered beneath desert soil, threatening to leach into the river that defines the region.

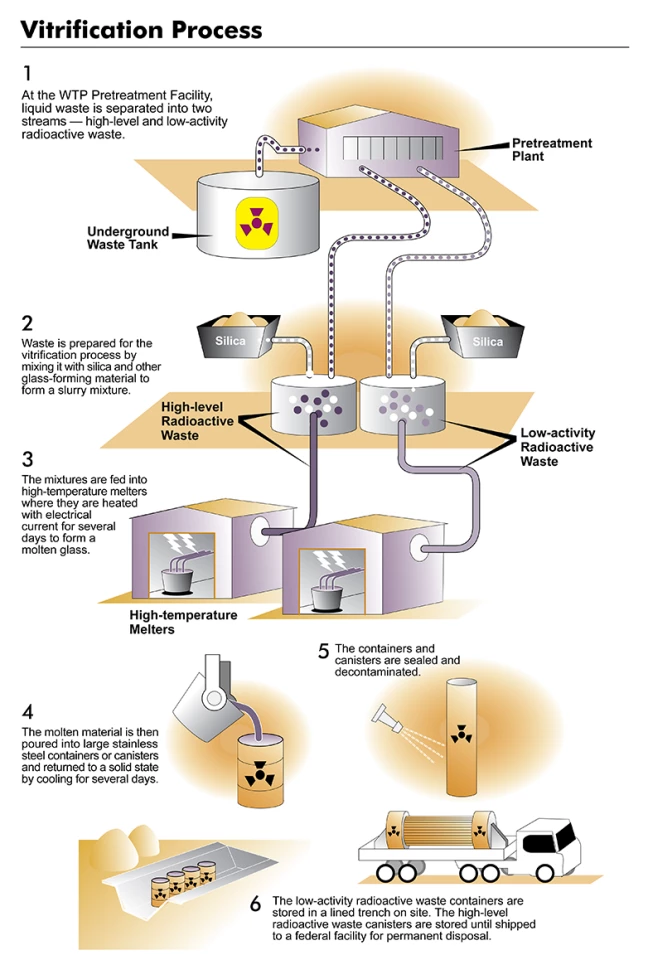

Now, the new vitrification facility, a US$10-billion engineering project built to immobilize that high-level waste in glass, has turned its first 5,500 liters into inert, permanent canisters.

Growing Up Beside a Closed World

As someone who grew up in the region, the weight of this story lands a little different. The Hanford site was always part of the landscape, even if it rarely came up in conversation. A place marked by long roads, distant fences, and the kind of silence that makes you wonder what has soaked into the ground. For decades, the story of Hanford – its scale, its secrecy, its consequences – was something I felt around the edges without ever fully understanding.

The Manhattan Project, that secret wartime race to develop the first atomic weapon, built Hanford with a speed that only a wartime effort can summon. Its reactors rose from the desert with unprecedented urgency, producing the plutonium that fueled both the Trinity test and the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Plutonium production continued throughout the Cold War into the 1980s, long after World War II ended, leaving behind a legacy far larger and more complex than anyone working behind those fences could have imagined. It was a project defined by speed and secrecy; its waste was never intended for long-term storage.

It wasn’t until much later, long after I’d moved away, that I began to understand how deep that silence ran. The vitrification plant, now operating for the first time, is a milestone I could never have imagined as a teenager in Richland. Even my high school mascot, the Bombers, treated history as something abstract. And let’s face it, as a kid, you spend less time worrying about war stories and more about what you’re going to wear to Friday night’s football game.

But coming back to this story as an adult is different. The ground feels different. The scale, more clear. For the first time, connections are established between the history that influenced the region, the scientific efforts aimed at addressing its challenges, and the ongoing responsibilities that lie before us. Only later did I understand that the waste buried beneath the soil was just as vast as the ambition that created it. Which is why the shift happening at Hanford now feels so significant.

The Shift Toward Permanence

That ambition is now being redirected toward restoration rather than production. The vitrification process represents a new kind of engineering legacy for Hanford, one defined by permanence rather than risk.

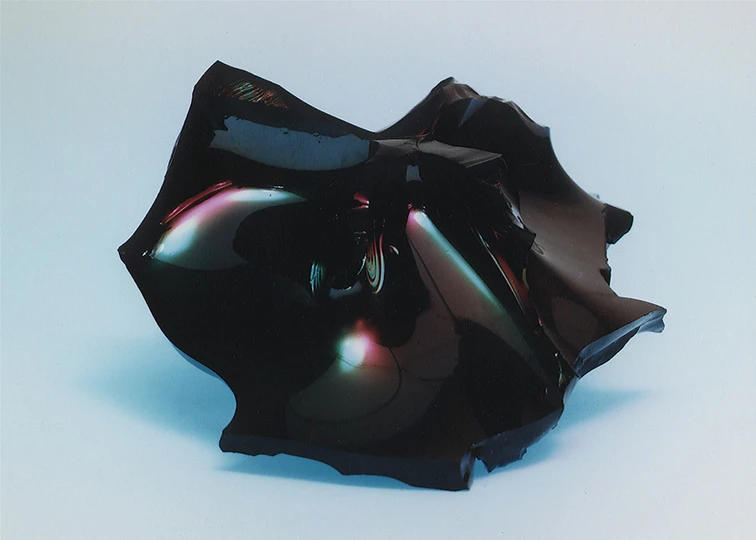

Inside the plant, a feed mixture of treated waste and glass-forming materials is heated until it becomes a molten slurry. At temperatures above 2,000 °F (1,093 °C), the radioactive compounds dissolve into the viscous glass, locking each element into a stable atomic matrix. Once cooled, the mixture solidifies into glass logs that are sealed inside stainless-steel canisters designed to hold for thousands of years.

Technicians have already produced the first 5,500 liters of vitrified waste, a small fraction of Hanford’s massive inventory, but a long-awaited start. Each glowing pour represents something more than containment. It’s proof that a radioactive problem once thought unsolvable can be immobilized, molecule by molecule.

The milestone also fulfills part of a long-standing consent decree known as the Tri-Party Agreement (TPA) and includes The Washington State Department of Ecology, the US Department of Energy and the US Environmental Protection Agency. Established to enforce federal and state commitments, it sets binding deadlines that compel progress through one of the most technically and politically complex environmental projects in the world. Environmental engineers and federal agencies have spent decades translating that mandate into infrastructure, balancing safety, cost, and chemistry in equal measure. Each advance under the decree reflects years of negotiation, testing, and patience.

When the Scale Finally Came Into View

Yet the decree is only the structure. The reality on the ground is far more complex. The clean-up at Hanford has never been a matter of simply removing waste and closing the gate. Many of the single-shell waste storage tanks were built with a planned lifespan of 20 years. They’ve now held radioactive sludge for more than 80 years, with several leaking and the remainder under constant monitoring to prevent the same fate.

Washington didn’t fully grasp the scale of the problem until the mid-to-late 1980s, when secrecy around the site finally began to lift. For the first time, state officials could see the scope of the problem they were being asked to help solve. As Ryan Miller from the Washington State Department of Ecology explained in an interview with New Atlas:

“Officials from Washington weren’t super tied in and didn’t know a lot of the scope of Hanford until … close to the middle end of the 1980s, the veil of secrecy was mostly unveiled a little bit and we signed the TPA and we started discovering the magnitude of cleanup that we had ahead of us," Miller told New Atlas.

The TPA became the state’s entry point into demanding accountability. Not as a symbolic gesture, but as a legally binding framework that governs everything from tank retrievals to groundwater treatment. It marked the shift from not knowing to finally being allowed to look.

Since then, the strategy has been a slow balance of science, engineering, and regulatory pressure. Waste is retrieved from aging tanks, contamination plumes are treated, and the vitrification plant has begun immobilizing certain high-level radioactive wastes in glass, a milestone that reshapes the future of the site but doesn’t soften its complexity.

Miller emphasizes that progress must be communicated honestly. The agency maintains that transparency is not just about releasing reports, but about presenting information clearly, accurately, and in a way that helps prevent misinformation from spreading. Public outreach, Miller said, is where that work becomes real. It is not only about what the agency knows, but how it shows up for the people who live next to the clean-up effort.

“One of the biggest things that's important to me personally from my program and my team is building relationships with the community,” said Miller. “Supporting the Hanford Advisory Board, trying to build connections through our outreach and education work. Whether it's connecting with schools or local community organizations and just getting out in the community. Showing up and being willing to answer questions and build some of that trust and transparency I think is really important.”

The Part the Maps Don’t Show

But technical challenges are only one part of the story. For all the engineering and oversight that define Hanford’s present, its most enduring consequences live in the people shaped by its past.

Radiation exposure doesn’t follow the timelines of clean-up milestones. It moves slowly, often invisibly, and shows up in ways that families learn to recognize long before agencies do. Across central and eastern Washington, you still hear versions of the same story: illnesses that appeared without warning, diagnoses that arrived too late, patterns that felt familiar even when no one could say with certainty what caused them.

Some of these stories belong to former workers. Others belong to people who simply lived nearby. Many belong to families who never received a clear answer at all.

I’ve seen echoes of that legacy in my own life.

Someone very dear to me, as close as a family member, sadly passed away from a common form of cancer seen in this region. And even in my immediate family, the long arm of exposure left its wake quiet, complicated, and impossible to fully trace. Growing up near Hanford you learn to live with questions you know will never be answered.

And that legacy, painful as it is, has not gone ignored by the agencies now responsible for the site. The state’s programs for former workers with qualifying illnesses are one attempt to acknowledge that history, and for some families they have been a lifeline. But acknowledgement is not resolution. It doesn’t untangle decades of secrecy, or bring clarity to the people who needed it most – people who, in a way, are ongoing casualties of a war that ended almost 80 years ago.

This is why the vitrification plant matters not just as an engineering milestone, but as a commitment to prevent future harm. It is a response to the very real cost carried by people who never chose to be part of the Manhattan Project’s legacy yet lived with its consequences.

And it is that history, both visible and invisible, that informs the path forward.

The Work That Outlives Us

What strikes me now is how vast the scale of this work really is. Not in acreage or budget, but in time. Clean-up at Hanford asks something unusual of the present: the willingness to take responsibility for consequences that will unfold far beyond our lifetimes. Few places make that demand so plainly. And that sense of scale becomes clearer when you look at how the work is shifting today.

The vitrification plant signals a shift toward that long view. It represents the point where engineering, oversight, and public accountability converge. Not to erase the past, but to keep it from repeating itself. Every milestone here carries the weight of what came before and the obligation to protect what comes after. That kind of work reshapes the usual definition of progress. It becomes quieter, steadier, more deliberate. And it changes how the site feels to someone who once grew up beside it.

When I look at Hanford now, even from a distance, I understand it less as a single site and more as a living commitment. A place where decisions ripple outward through ecosystems, communities, and generations. A place where science and history meet, not neatly, but honestly. A place that continues to ask hard questions about what we inherit and what we leave behind.

Seen this way, the work becomes less about milestones and more about continuity. The kind that stretches long past any one moment in time. Clean-up here will not end with a ribbon cutting. It will unfold slowly, responsibly, across generations who will never meet one another. But that, in its way, is the measure of the work: a recognition that some legacies demand long memory, steady hands, and the kind of care that outlasts the people who first give it shape.

Editor's note (Dec. 16, 2025): This article originally stated the nuclear production facility in Washington state was "dubbed" the Hanford site. A number of commenters have pointed out this is the actual name of the facility. The text has been updated to reflect this. We apologize for the error and thank those who brought this to our attention.