Last year, Apple teamed up with scientists at the University of Michigan (UM) to study how noise pollution can impact the hearing health of humans. Examination of the data before and then during the stay-at-home and social distancing orders implemented in response to the coronavirus pandemic has revealed some interesting trends, notably that people’s exposure to environmental noise dropped by nearly half.

As many parts of society around the world ground to a halt to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus this year, it led to sharp declines in various forms of pollution. This included significant decreases in nitrogen dioxide over China and Italy, as well as an “extreme dip” in global carbon emissions.

The new analysis of data from the Apple Hearing Study reveals a similar trend concerning another type of pollution, in the volume of sounds the typical person is exposed to. The study is designed to gauge exposures to environmental sound at a national level and build a clearer picture of hearing health among Americans, and the pandemic threw up an interesting curveball.

The researchers gathered data from almost 6,000 participants in Texas, Florida, California and New York, amounting to more than 500,000 daily noise level readings. These were collected from Apple Watches and iPhones and cover the period before the pandemic as well as once the stay-at-home and social distancing orders were implemented.

On average, the analysis revealed a reduction in each person’s daily sound levels of three decibels, or nearly half, once the lockdown measures had been taken, as study author Rick Neitzel explains.

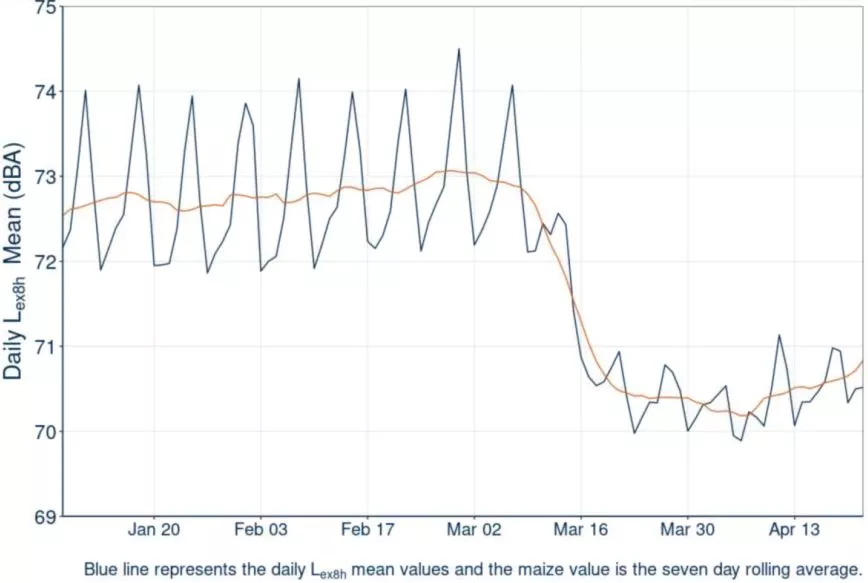

"When sound exposures are described using the decibel scale, a 10-dB change is equivalent to a 10-fold increase or decrease in sound energy, and a 3-dB change is equivalent to a halving or doubling or sound energy," he tells New Atlas. "The average daily sound exposure we observed prior to the COVID-19 lockdowns was 73.2 decibels, and the average sound exposure post-lockdown was 70.6 decibels, for a reduction of roughly three decibels. This roughly 3-dB reduction in sound exposure is equivalent to a halving, or 50 percent reduction, in average daily sound energy among our participants."

These occurred at differing rates and to different degrees depending on the location, which was reflected in the team’s analysis.

“California and New York both had really drastic reductions in sound that happened very quickly, whereas Florida and Texas had somewhat less of a reduction,” says Neitzel.

The analysis also showed the largest drops in noise could be seen over the weekends, where nearly all subjects reduced their time spent enduring noise above 75 decibels, which is the level that official bodies such as the World Health Organization consider safe. This combined with more people working from home leveled the playing field in a sense, meaning that weekdays didn’t look all that different to weekends in terms of noise pollution.

“People’s daily routines were disrupted and we no longer saw a large distinction in exposures between the traditional five working days versus the weekend,” says Neitzel.

A paper describing the research was published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

Source: University of Michigan