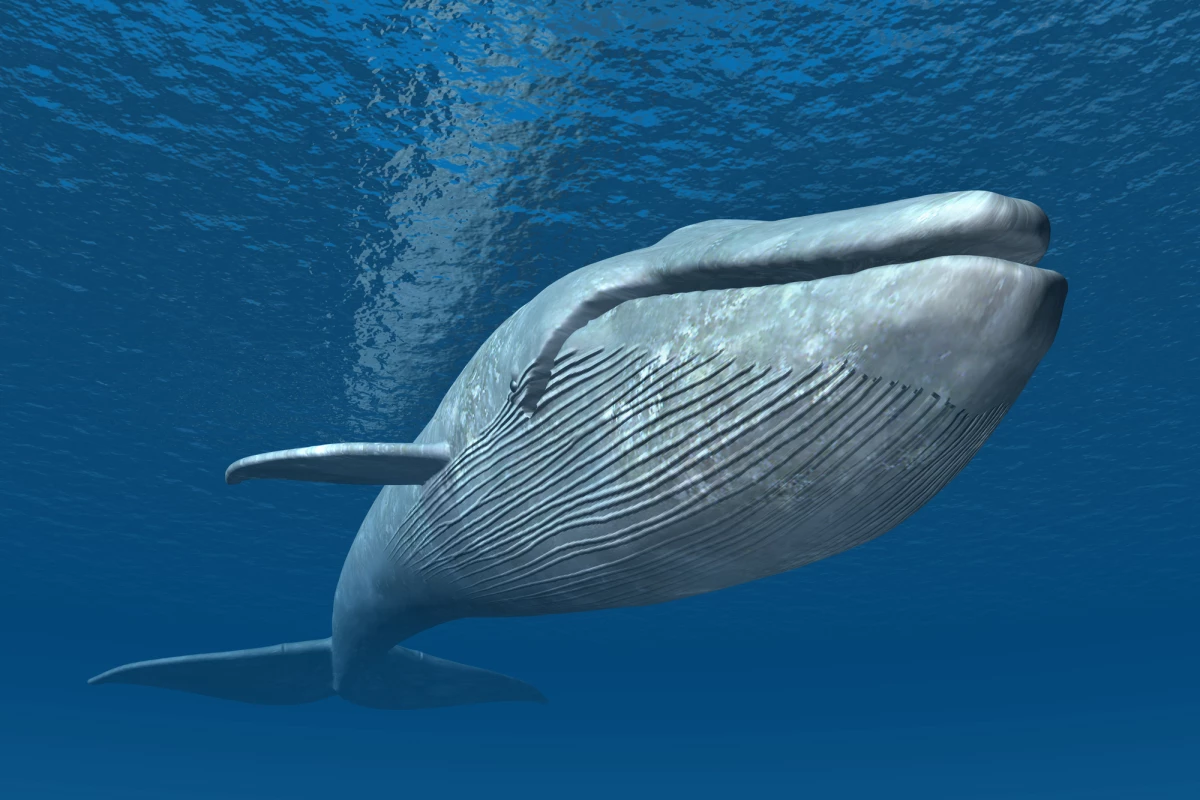

We know that marine animals of all sizes are inadvertently consuming plastics as they move through the ocean, but what does this diet look like for the largest of them all? To answer this question, scientists at Stanford University have analyzed the foraging habits of whales off the coast of California and found that blue whales take in an estimated 10 million pieces of plastic each day.

The study is a continuation of field research carried out by biologists and ocean scientists at Stanford that amounts to more than a decade of data on whales and their feeding habits. This involves drone observations, non-invasive tags and the use of small research vessels and sound waves to map dense gatherings of fish and krill in the whales’ feeding areas.

For the first time, the researchers have now combined this information with measurements on microplastic concentrations in the water column off the coast of California. The new analysis showed that the whales do the majority of their feeding 50 to 250 m (164 to 820 ft) below the surface, where the highest concentrations of microplastics can be found in the open ocean.

But rather than slurping up the microplastics with seawater as they open their mouths and lunge after swarms of krill and fish, the scientists found the whales are consuming the fragments as they eat the prey itself. For blue whales, the largest creature on the planet with a diet heavy on krill, this means it is ingesting an estimated 10 million tiny pieces of plastic a day.

“They’re lower on the food chain than you might expect by their massive size, which puts them closer to where the plastic is in the water,” said said study co-author Matthew Savoca. "There’s only one link: The krill eat the plastic, and then the whale eats the krill.”

As part of their analysis, the team also looked at the impacts on humpback whales, which feed primarily on herring and anchovies and were found to ingest an estimated 200,000 microplastic pieces a day. Fin whales, meanwhile, eat both krill and fish and are ingesting an estimated three to 10 million microplastic pieces a day. That the plastics are being consumed with the prey is a concern for the scientists, who are troubled by the unknown repercussions for the animals’ nutrition.

“We need more research to understand whether krill that consume microplastics grow less oil rich, and whether fish may be less meaty, less fatty, all due to having eaten microplastics that gives them the idea that they’re full,” said lead author Shirel Kahane-Rapport. “If patches are dense with prey but not nutritious, that is a waste of their time, because they’ve eaten something that is essentially garbage. It’s like training for a marathon and eating only jelly beans.”

Learning more about the nutritional impacts of this microplastic pollution is among the next steps for the researchers, along with efforts to better understand the oceanic forces that lead to its accumulation in dense patches amid the whales’ prey.

“Understanding more about the basic biology of baleen whales and whale ecosystems through the use of new technologies like drones, biologging tags, and echosounders enable us to perform important translational research in sustainability and beyond,” said senior study author Jeremy Goldbogen.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Stanford University