Recently, drought seems to be a fact of life. As the lead photograph poignantly illustrates, most of the U.S. has been struggling with serious levels of drought for the past several years. Worldwide, drought affected areas include Europe, India and Pakistan, Russia, much of Africa, South America – the list goes on. But when the rains start again, everyone expresses great relief, not realizing that long-term depletion of groundwater reserves is part of the price for surviving drought. It was with this in mind that GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment), a joint U.S. and German space project, was designed a decade ago.

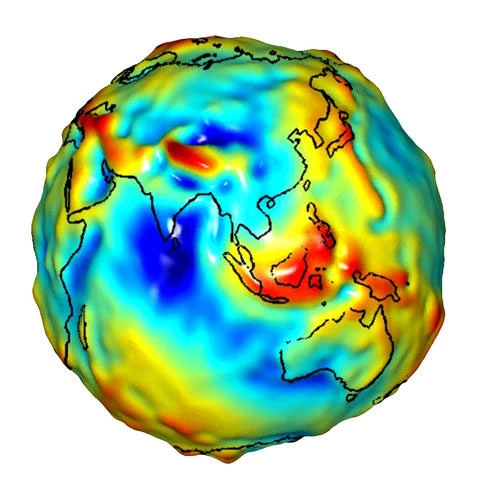

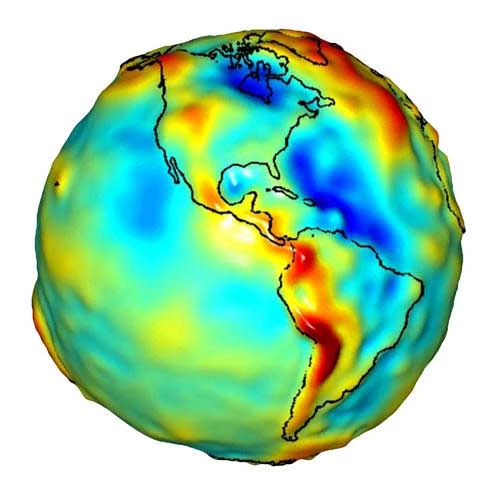

The GRACE mission consists of a pair of satellites designed to accurately map variations in the Earth's gravitational field. The two identical satellites are in a polar orbit some 500 km (310 miles) above the Earth, spaced a distance of 220 km (137 miles) apart along the same orbit. The distance between the satellites is continually measured using GPS and radar.

To people on living on Earth, gravity appears to be constant. However, it varies slightly from place to place. If there is a massive flood in India, the GRACE satellites are pulled toward the flooded plains a tiny bit more than normal. The first satellite to approach the flooded region will feel a slightly larger gravitational pull than before because of the mass of all that water. The speed of the satellite doesn't change, so it goes to a slightly smaller altitude. This changes the distance between the two satellites, which is recorded to within 10 microns (0.0004 inches), or about one part in twenty billion. By tracking trends in how the satellites’ orbits change, scientists and engineers can calculate how gravity is changing on Earth.

What can we learn from accurate measurements of Earth's gravity? The thickness of ice sheets and glaciers, the temperature of large-scale ocean currents, motions of magma, better profiles of the atmosphere, and also the amount of water stored in the ground.

Groundwater is the source of artesian springs throughout the world. It is also the main source of water for drinking and farming for much of the world. In the U.S., 37 percent of water from growing crops and 51 percent of drinking water comes from groundwater. The water table in India's wheat, rice, and barley-growing northern regions has been dropping over a foot (30 cm) per year. The water table under Moscow fell 300 feet (91 m) over the last century. Groundwater is not only a precious resource, but an overused one.

During a drought, groundwater reserves take multiple injuries. Clearly, farmers use more groundwater for irrigation when rainfall has been insufficient for growing healthy crops. This removes large amounts of water from the aquifers. A second blow is that water which would have penetrated the aquifers to refill them never fell, and much of what did fall evaporated.

It also takes time for surface water to make its way into the aquifers. The Ogallala aquifer in the central states is the largest aquifer in the U.S. It originally held some 865 cubic miles (3600 cubic km.) of water – most of it preserved from the last Ice Age. The rate of refill from surface waters is exceedingly slow, and some predictions suggest that the Ogallala will effectively be depleted within the current century.

A different sort of injury associated with overuse of groundwater is pollution. If a well is near the shore, excessive use is likely to draw the water table locally below sea level, in which case salt water will seep into the aquifer. If a source of pollution lies between the main parts of an aquifer and a particular well, overuse of the well will draw that pollution into the aquifer, but even more so into the water being drawn from the well.

The largest problem met in trying to manage groundwater resources is that the reduction in groundwater has been largely invisible. Scientists could get a feeling for how the aquifers are evolving by measuring water level in wells, but that gives rather crude results, with effects often showing up years after their causes.

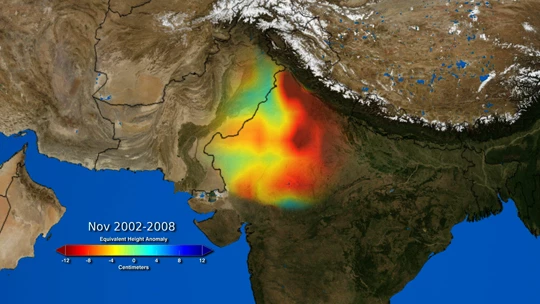

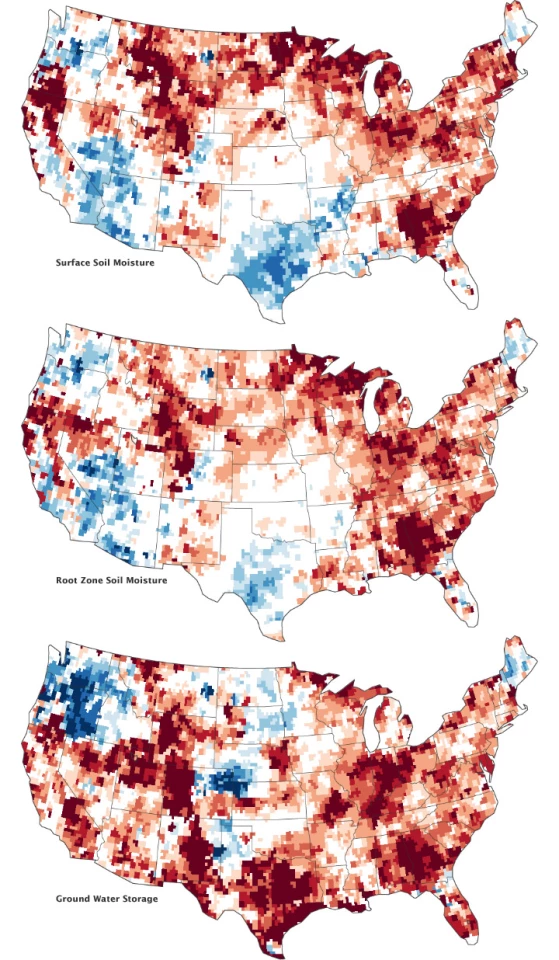

All this is now being changed by GRACE. As shown in the image above, GRACE can measure surface soil moisture, root zone soil moisture, and groundwater. Blue areas are high in groundwater, while red areas are dry. The top image is moisture in the upper 2 cm (0.8 inches) of soil, the center image shows moisture at root level (roughly the top meter (40 inches) of soil), and the lower image shows groundwater in aquifers. It is clear that the pattern of the drought is more solidly etched in the groundwater depletion. Surface waters can recover from a few good rains, but it takes more than that to restore water removed from aquifers.

The video below presents a time-lapse view of the groundwater situation for the U.S. over the past ten years. Fresh water is clearly another nonrenewable resource which requires active management in real-time. The next generation of GRACE satellites will help guide the way.

Source: GRACE