For much of the first year of the pandemic researchers watched the SARS-CoV-2 virus mutate and change as it spread across the globe. This was expected. Viruses constantly mutate. In fact, genomic changes in a virus can be so pronounced from person to person scientists are able to track chains of transmission in stunning detail.

The vast majority of mutations initially seen with SARS-CoV-2 were relatively benign. No particular variant seemed to be outperforming any other. By the end of 2020, however, a new SARS-CoV-2 variant had become notably predominant in the United Kingdom.

Initially dubbed B.1.1.7 (also informally known as the UK or Kent variant) the variant’s rapid spread clearly indicated certain mutations had generated significant transmission advantages. Since then, researchers have been able to home in on the particular genomic features unique to this variant and flag other viral lineages with similar features.

In May, the World Health Organization (WHO) stepped in to help clarify the growing confusion over variant names. While scientists often referred to these new variants by their particular lineage label (B.1.1.7; B.1.351; B.1.617.2; etc), many found it easier to tag a variant by its place of origin (UK variant; South African variant; Indian variant; etc).

Noting the “stigmatizing and discriminatory” nature of labeling a variant with a geographical name the WHO introduced a universal naming system based on letters of the Greek alphabet. Scientific lineages were still still recommended for research purposes but national authorities and media outlets were urged to adopt these new, neutral labels.

But if novel variants are emerging all the time when does one attain an official label?

The WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on Viral Evolution has established three tiers of classification for novel SARS-CoV-2 variants: Alerts for Further Monitoring, Variants of Interest, and Variants of Concern.

Now that scientists are getting a grasp on what kinds of genomic mutations can significantly alter the severity or transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2, novel variants with the potential to become problematic can be detected sooner. These variants are labeled with an Alert for Further Monitoring.

The current working definition for this WHO designation is: “A SARS-CoV-2 variant with genetic changes that are suspected to affect virus characteristics with some indication that it may pose a future risk, but evidence of phenotypic or epidemiological impact is currently unclear, requiring enhanced monitoring and repeat assessment pending new evidence."

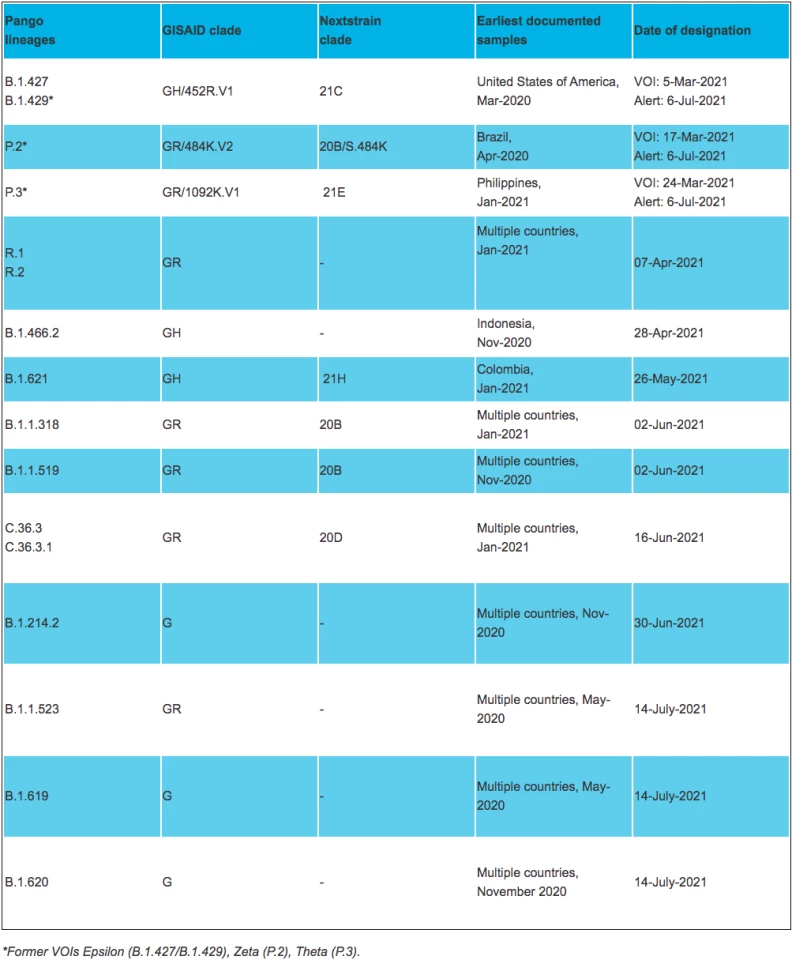

There are currently 13 circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants designated Alerts for Further Monitoring.

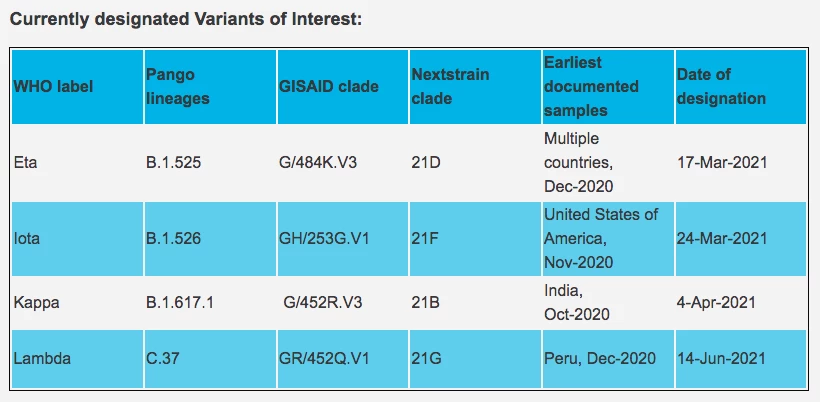

The next classification tier is a Variant of Interest (VOI). These variants have genetic changes known to influence virus characteristics and they have produced significant community clusters in several locations.

Only when a variant is classified a VOI is it labeled with a Greek alphabet character. There are currently four VOIs designated by the WHO.

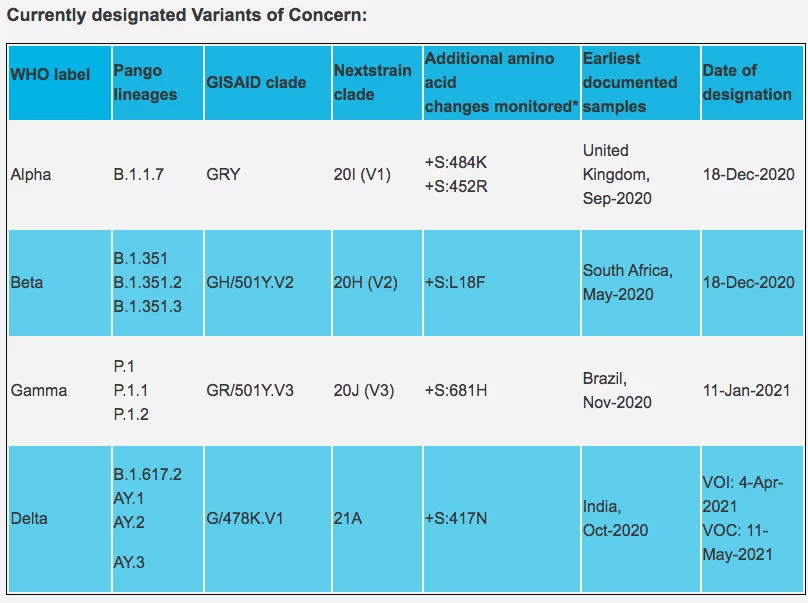

The final tier is a Variant of Concern (VOC). A VOC is a variant that has demonstrated either a significant increase in virulence or disease severity.

So far, there are four official VOCs and they are mostly defined by their increases in transmissibility. A variant does not need to have spread significantly for it to be classified a VOC. If evidence is found a new variant can evade vaccines or current therapeutics it will be classified as a VOC.

Although there are currently eight official VOIs/VOCs, there are another three variants with Greek alphabet labels that have recently been reclassified down into the Alert designation. Epsilon, Zeta, and Theta were all previously classified as VOIs before being dropped down a designation as more epidemiological evidence was gathered.

The WHO says former VOIs/VOCs will retain their previous designation for the time being while they are monitored. So Epsilon, Zeta, and Theta currently still hold those labels, meaning 11 of the 24 characters in the Greek alphabet are currently used to designate SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The WHO labels are generally accepted by most governments around the world, although some regions do have their own variant classes. In the United States, for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) follow similar designations to the WHO with its own VOI and VOC categories.

The CDC does, however, present a tier of variant classification higher than VOC, called Variant of High Consequence (VOHC). It essentially covers variants with clear evidence of a significant reduction in vaccine effectiveness or variants that appear to present severe clinical disease. Reassuringly, there are no SARS-CoV-2 variants currently in this designation.

For those keeping score, Lambda is the latest variant to be given a WHO label in the VOI category. It was designated a Variant of Concern in June 2021 after significant spread was detected in Peru over the prior months.