Amid ongoing debate about red meat’s role in human health, a new risk has emerged. Researchers have shown that a gut-bacterial byproduct of eating red meat and other animal products is linked to the development and progression of abdominal aortic aneurysms – particularly in older men.

In a new observational study, Cleveland Clinic researchers set out to examine whether high blood levels of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) – a compound produced when gut microbes metabolize nutrients in red meat and other animal products – might be driving this silent and potentially deadly vascular disease. Earlier studies have tied TMAO to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, but less is known about its role in abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA).

"We currently have no therapies except surgery or percutaneous intervention to treat abdominal aortic aneurysms that are particularly effective, and we have no blood tests to predict who is going to have an aneurysm and who will do well," said lead author Scott Cameron, M.D., section head of Vascular Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

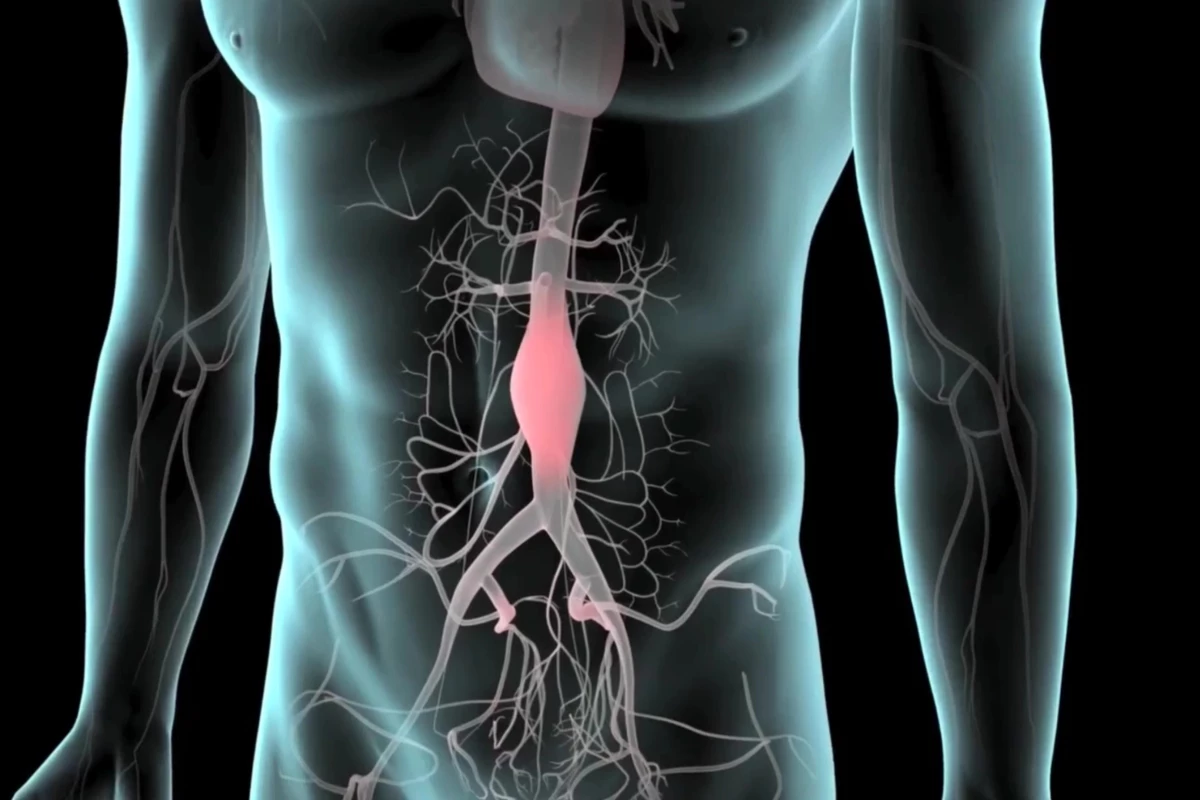

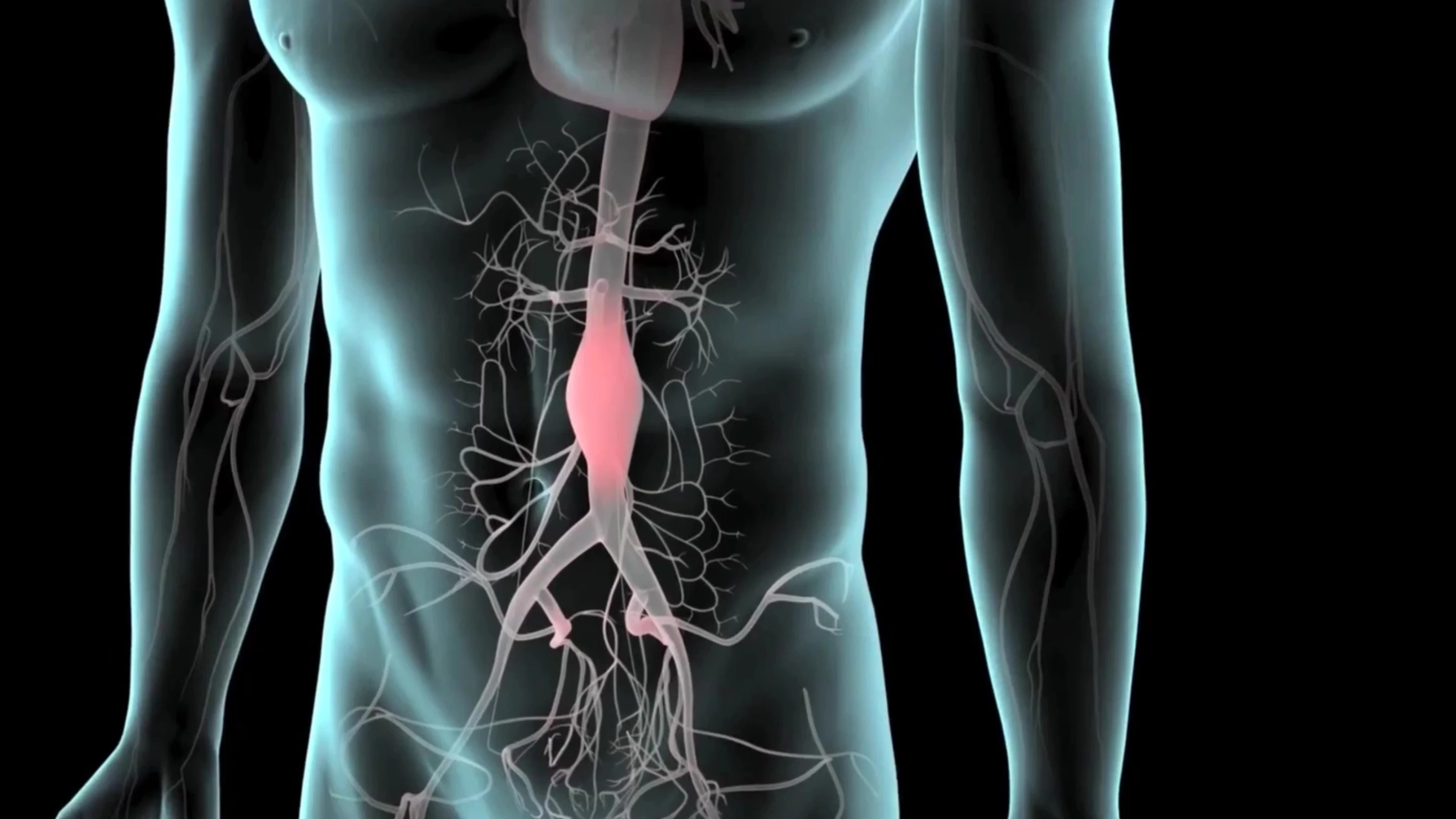

An abdominal aortic aneurysm, or AAA, develops when a portion of the abdominal section of the aorta – the body’s main artery – becomes weakened. As the aortic wall loses strength, it can balloon outward, forming an aneurysm that slowly enlarges, often without symptoms. The danger comes if it ruptures, leading to sudden internal bleeding that is often fatal.

Scientists don't yet fully understand the underlying causes of these AAAs, but there are risk factors – age and sex, smoking, genetics and other cardiovascular comorbidities. It's estimated that somewhere between 3.9-7.7% of men aged 65 years and above will develop an AAA.

So, back to red meat. Essentially, when you eat foods rich in carnitine (abundant in red meat) or choline (eggs, dairy, some fish), gut microbes break these products down into a precursor called trimethylamine (TMA). TMA is absorbed through the gut wall into the bloodstream and carried to the liver, where it’s converted by flavin-containing monooxygenase enzymes (FMO3 in particular) into TMAO. So while it begins in the gut, and AAA develops in the abdomen, the pathway is complex.

“TMAO is made by gut microbes, with levels being higher when eating animal products and red meat,” said senior author Stanley Hazen, M.D., chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Cardiovascular and Metabolic Sciences Department.

In the US, around 10,000 people die from AAA each year, most over the age of 60. These aneurysms are most often symptomless – and, like we said, there are no drug treatments to halt their progression. If by chance an AAA is detected, it'll most likely be monitored via regular scans until surgery becomes necessary. So identifying a new, measurable risk factor could be game-changing and life-saving.

Which is where this study breaks new ground. The researchers set out to examine whether people with higher TMAO levels were more likely to have an aneurysm, whether those levels predicted faster growth and progression, and whether TMAO could be used as a biomarker or even a therapeutic target.

The researchers studied nearly 895 adults across two independent groups, one in Europe (237 participants; 89% male, average age 65 years) and a Cleveland Clinic cohort based in the US (658 participants; 80% male, average age 63 years). All participants were already being monitored for existing aneurysms or early aortic dilations. Each person had their blood plasma tested for TMAO and underwent ultrasound or CT scans to measure and track aneurysm size.

The team tracked whether higher baseline TMAO levels correlated with faster aneurysm expansion – a growth of 4 mm or more per year, or if it reached the 5.5-cm threshold requiring surgical intervention. Statistical modeling also adjusted for age, sex, smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes.

What they found was that, across both study groups, patients with the highest blood TMAO levels were nearly three times more likely to have an aneurysm. In the Europe cohort, participants with elevated TMAO levels were 2.75 times more likely to experience fast-growing aneurysms, and 2.67 times more likely to need surgery for the condition. This was mirrored in the US study – patients with high TMAO were 2.71 times more likely to have fast-growing aneurysms and 2.73 times more likely to need surgery.

The similarity between the two groups strengthens the case for using TMAO as a predictive measure to identify people most at risk of developing this serious condition.

"These results suggest targeting TMAO levels may help prevent and treat aneurysmal disease beyond surgery," said Cameron. "With one of the largest volumes of aortic cases in the United States, we hope we can apply these findings to help future patients."

These findings build on the knowledge gained through earlier animal experiments, which demonstrated how artificially raising TMAO levels in mice accelerated aneurysm growth – and blocking its production could slow or stop it.

Together, these findings suggest that TMAO may not just be a passive marker of AAA but an active driver of it. And understanding the link is critical, given the nature of these aneurysms that can grow, unnoticed, until they rupture. Somewhere between 80-90% of people who suffer a sudden AAA rupture will die before even making it to the emergency room. For those who do make it onto the operating table, around 50% will die during surgery.

Unlike high cholesterol or high blood pressure, there are currently no drugs to halt the growth of abdominal aneurysms. However, if TMAO contributes to the development of AAA, then drugs or dietary changes could be a useful first line of defense against this "silent killer."

Importantly, the findings don’t single out red meat as the sole culprit. TMAO emerges whenever gut microbes convert carnitine and choline into the compound, and as stated, these nutrients are found in a variety of animal-based foods, including eggs and some seafood. However, these findings again show how diet and the gut microbiome interact to influence vascular health.

“Medication targeting this pathway has been shown to block aneurysm development and rupture in preclinical models but are not yet available for humans," Hazen said. "These results are important to share because they show how important diet may be in helping prevent or treat patients with aorta dilation or early aneurysm compared to current clinical practice, which is to monitor until surgery is needed.”

The research was published in the journal JAMA Cardiology.

Source: Cleveland Clinic