Sitting in the heart of Manhattan is the iconic Belasco Theatre. Over a century old, this truly legendary Broadway venue has been influencing popular culture for decades, from introducing the world to Marlon Brando in the 1940s to bringing modern classic Hedwig and the Angry Inch into mainstream Broadway circles in 2014.

From November, for the first time in the Belasco’s history, the theater will become a movie house, screening Martin Scorsese’s latest gangster epic The Irishman. Netflix, the film’s producer, has hired the entire theater for one month, and will retrofit it into a cinema. The film will be scheduled to screen using a classic Broadway performance model - one evening session per day, with additional matinees on weekends.

“The opportunity to recreate that singular experience at the historic Belasco Theatre is incredibly exciting,” exudes Scorsese in a Netflix press release. “Ted Sarandos, Scott Stuber, and their team at Netflix have continued to find creative ways to make this picture a special event for audiences and I’m thankful for their innovation and commitment.”

Netflix’s unusual, and most likely expensive, gambit to screen the film in such a striking way is undeniably a tribute to both the legend of Martin Scorsese and the filmmaker's intimate relationship with the city of New York. But is this the only reason the streaming giant is mounting such an unconventional event?

The Hollywood monopoly

In the first half of the 20th century Hollywood ruled the world of entertainment. Major studios would produce films and then screen that content in theaters they owned. It was a thorough, vertically integrated business, and unsurprisingly eventually ran afoul of government antitrust authorities in the 1940s.

A massively influential antitrust case between the US government and Paramount Pictures reached the Supreme Court in 1948, leading to a landmark decision that entirely dismantled the power structures of the old Hollywood system. Studios were not explicitly banned from owning movie theaters but it did rule that the system was in violation of antitrust laws.

Studios rapidly sold off their theater businesses, and the rise of television allowed them to pivot to a whole new mode of exhibition. For the rest of the 20th century the world of cinema existed in a fragile but stable equilibrium. Movie studios and big movie theater chains symbiotically worked together.

Technology, of course, meditated several shifts in exhibition over the years. VHS, cable, DVD, Blu-ray and ultimately streaming, all offered studios new ways to distribute content. Movie theaters were still the primary mode of exhibition for film, but theater chains were increasingly feeling threatened.

The fragile release window agreement

In the early 1980s the introduction of home video arguably kicked off the chain reaction we are seeing the consequences of today. In order to maintain the primacy of theatrical exhibition, theater chains and movie studios agreed upon a principle called “release windows”. This meant that if a studio wanted to screen a movie in theaters it would have to wait an agreed upon duration before releasing the title on home video.

Initially, these release windows were long – at least six months before a film could move to any secondary platform after theatrical screening. But those windows slowly but surely shrunk, as home entertainment mediums evolved.

The equilibrium between Hollywood studios and major theater chains became increasingly volatile as the industry moved into the brave new world of the 21st century. Hollywood still understood the primacy of theatrical exhibition, both from a historical perspective and a financial one, but a constant push/pull of negotiations with theater chains ultimately whittled the window down to 90 days.

This was a line that could not be crossed. Major theater chains were unified on this. For a film to receive a major theatrical release it could not move to any other platform for 90 days from the day it opened.

Enter Netflix…

It is impossible to understate how fundamentally disruptive Netflix has been to the film industry. As a business model, Hollywood has essentially relied on ticket sales to make its money. Home entertainment such as DVDs or cable TV licensing has been important, but billions are still made every year by enticing audiences to buy tickets and see films in theaters.

Netflix doesn’t work that way. Netflix makes it money from subscriptions. Its bottom line is dependent on luring new subscribers and maintaining current ones. The company cleverly realized many years ago that it couldn’t rely on a streaming library full of content it didn’t control, so it started making its own content. Initially, it concentrated on producing serialized television. House of Cards was its first original show to hit the platform in early 2013.

The streaming service was a little slower to dip its toe into the world of filmmaking. Its first salvo into film came in 2015 when it bought the distribution rights for a film called Beasts of No Nation. Caring little for traditional release windows or theatrical screening, Netflix immediately came into conflict with major theater chains in the United States.

Four major theater chains joined forces to make a stand. The film would only screen in their theaters if Netflix abided by a 90 day release window.

Netflix refused ...

Its business model is subscriptions and there was little interest from the streaming company in embarking upon a complex and expensive broad theatrical screening campaign. A few million dollars derived from theatrical box office revenue was nothing compared to its multi-billion dollar subscription revenue. If you wanted to see the film, Netflix demanded you sign up. Why would it want you to go to a cinema and see it?

The lure of the Oscar

One thing Netflix was interested in, however, was awards. For several years insiders have suggested Netflix desperately wants a Best Picture Oscar, but to qualify for Oscar consideration a film must screen in at least one LA county theater for seven days. From that perspective, Netflix has effectively cultivated relationships with smaller independent movie theaters who are not particularly bothered by traditional release windows.

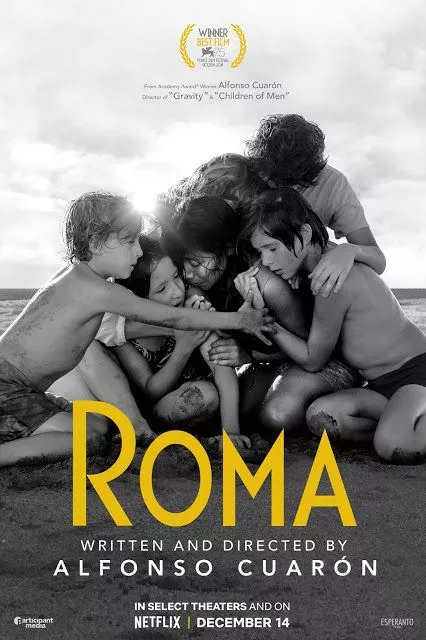

What Netflix quickly realized was to win awards it would need to attract famous big-name filmmakers, and famous big-name filmmakers do generally prefer their films to screen in movie theaters. Luring artists such as the Coen brothers and Alfonso Cuaron in 2018 offered Netflix its biggest chance at an elusive Oscar. As the year progressed Cuaron’s gorgeous Roma rapidly looked like it could actually cross the Rubicon and deliver Netflix its sought-after statuette.

The company somewhat loosened its strict streaming-only release strategy and offered movie theaters its version of an olive branch. It would offer a one-month window to theaters interested in playing the film.

This wasn’t good enough for the major theater players though. They were unwilling to budge from the 90-day limit.

In the lead up to the Oscar ceremony in February 2019 Roma was an unexpected Best Picture favorite. Netflix seemed on the cusp of finally capturing its white whale. Some Oscar insiders suggested Netflix spent between US$40 and $60 million promoting the film in the lead up to the event. It wanted that Best Picture award and money was no object.

A fascinating counter-campaign began to build against Netflix. The old Hollywood guard obviously did not appreciate this young disruptor coming in and taking over the industry. One insider was reported as saying, “A vote for Roma means a vote for Netflix. And that’s a vote for the death of cinema by TV.”

Even legendary filmmaker Steven Spielberg took a veiled swipe at Netflix in the lead up to the Oscars. Despite not mentioning the streaming service by name, Spielberg argued seeing films in theaters is the ultimate way to enjoy movies and that experience must be preserved. Spielberg has in the past suggested a film made by a streaming service is akin to a TV movie and shouldn’t necessarily qualify for Oscar consideration.

In the end, Roma was pipped at post, losing its Best Picture Oscar to a film called Green Book. The film still won Best Foreign Film, Best Cinematography, and Best Director, however.

The Scorsese gambit

For over a decade legendary American filmmaker Martin Scorsese has been trying produce a film adaption of a book called I Heard You Paint Houses. The story is based on the true tale of an infamous mob hitman, and, of course, it seemed like the perfect match for a filmmaker such as Scorsese.

Titled The Irishman, the film was initially budgeted at an incredible $100 million. Scorsese made the decision to deploy state-of-the-art de-aging technology to make his exceptional cast of Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci look 30 years younger in flashbacks. Questions over the cost and efficacy of the technology led the budget to skyrocket, and US distributor Paramount Pictures pulled out of the film in early 2017.

In swooped Netflix, saving the day for Scorsese’s truly epic gangster passion project. Over the next two years rumors swirled suggesting the ambitious visual effects were not working and the budget reportedly ballooned, with some reports claiming it had reached an astounding $200 million dollars.

All of this was financed by Netflix, determined to let the legendary filmmaker make the film he wants. In the end, the film was reported to have cost $159 million.

Traditionally, massive multi-year passion projects from great filmmakers don’t turn out that well and the signs around The Irishman were certainly concerning. Post-production effects troubles and a huge budget gave the impression the film could be a grand folly. When the nearly four-hour running time was eventually revealed it seemed to validate the foolishness of the Netflix filmmaking model. Sometimes, even great filmmakers need restrictions and oversight. Netflix’s blank cheque model had rarely resulted in great art.

And then the film finally premiered at the New York Film Festival in late September. It is fair to say the majority of reviews were glowing. Critics called the film “a remarkable achievement”, a “long-form knockout”, and one of Scorsese’s “most satisfying films in decades”. It looked like Netflix has a serious Oscar contender on its hands from one of the world’s truly legendary filmmakers.

But what about that pesky theatrical exhibition problem?

Martin Scorsese is an old-school filmmaker. He is, of course, an advocate for the big screen experience and has clearly expressed a preference for theatrical film screenings. Netflix, on the other hand, simply does not care about screening its films in theaters. Other than the bare minimum of theatrical requirements to qualify for Oscar consideration, Netflix’s model is to get content onto its streaming platform as soon as possible.

But, Netflix was faced with a quandary. It needed to keep Martin Scorsese happy, to help pave the way for more relationships with big name filmmakers. The 90-day release window was still a sticking point for all the big US theater chains. AMC, Regal and Cinemark, accounting for thousands of screens across the country, all said no to Netflix. They will not screen this landmark film if Netflix doesn’t play the 90-day waiting game.

Netflix scrambled to cobble together a short one-month run for the film in the United States, making deals with smaller independent theater chains such as the Alamo Drafthouse. But was this enough to appease the concerns of Scorsese?

And so we return to the strange case of an iconic New York theater being retrofitted to screen films for the first time its 112-year history.

The Belasco Theatre in New York City will screen the film for one month starting on November 1st. The film will then appear globally on Netflix on November 27th, available for hundreds of millions of subscribers to watch on their televisions at home.

The Irishman is one of at least 10 films Netflix is offering limited theatrical releases for over the next few months. Some of the screenings are limited to just a few venues before appearing on the streaming service as little as one week later. Others, such as Noah Baumbach’s Oscar tipped Marriage Story, will get a broader one-month roll out before hitting the global streaming service. None of these films will screen in any major theater chain.

The line has been drawn. Neither Netflix nor the theatrical chains are budging. So the big question we are left with is whether Netflix is about to win the war and get its Oscar next year. And if it does win Best Picture with The Irishman it will be the final disruption for a film industry struggling to navigate a rapidly changing exhibition landscape.

Netflix may reasonably seem like an existential threat to major theatrical exhibitors, but is this a war the theaters can win?

And when significant films from great American artists are essentially blacklisted from widespread theatrical screenings by nervous exhibitors trying to protect an old business model, one has to ask whether this attempt to preserve theatrical business will actually cause more harm than good.