Carbon nanotubes promise to revolutionize everything from medicine to electronics and power generation. Unfortunately nanotubes are notoriously hard to work with and chemists worldwide have struggled for years to even make them. Now researchers have unveiled a method for the industrial-scale processing of pure carbon nanotube fibers that builds upon the tried-and-true processes that chemical firms have used for decades to produce plastics.

One of the main reasons plastic is so cheap is because of the massive throughput that’s possible with fluid processing. Polymers can be melted or dissolved and processed as fluids by the train-car load and adopting the same technique to allow the processing of carbon nanotubes as fluids opens up all of the fluid-processing technology that has been developed for polymers.

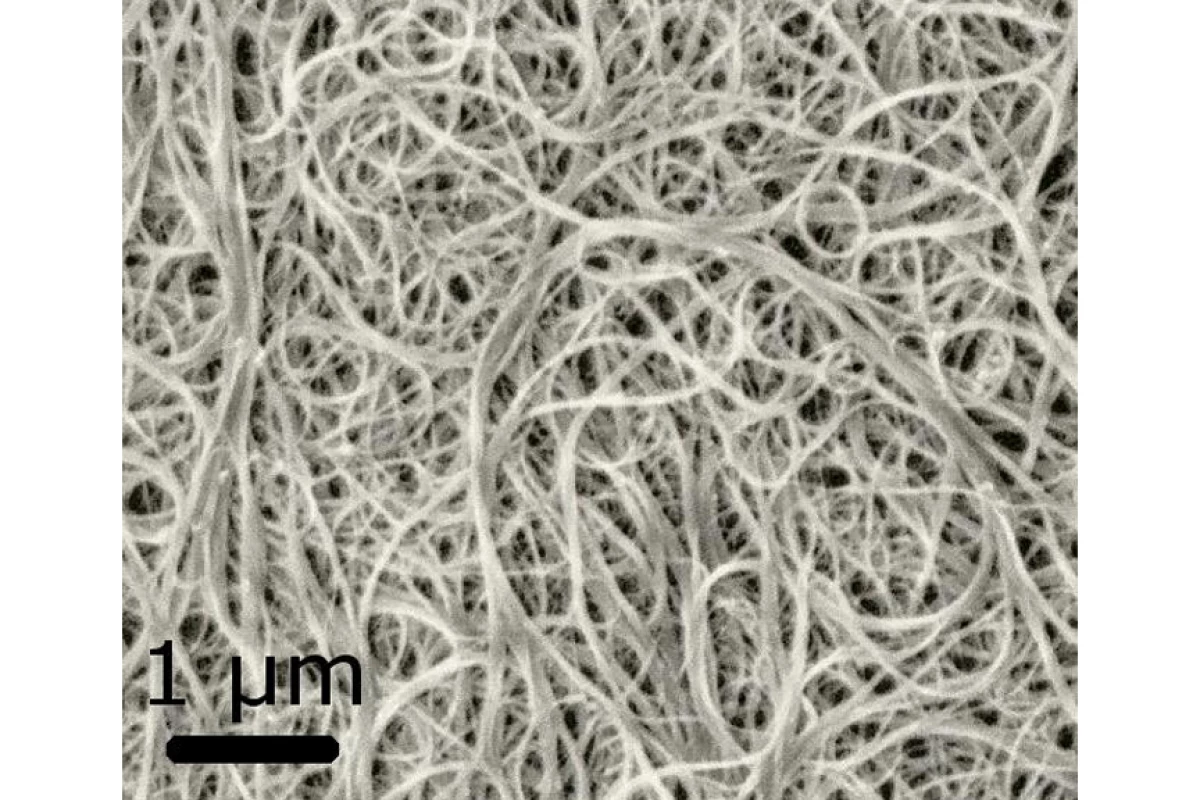

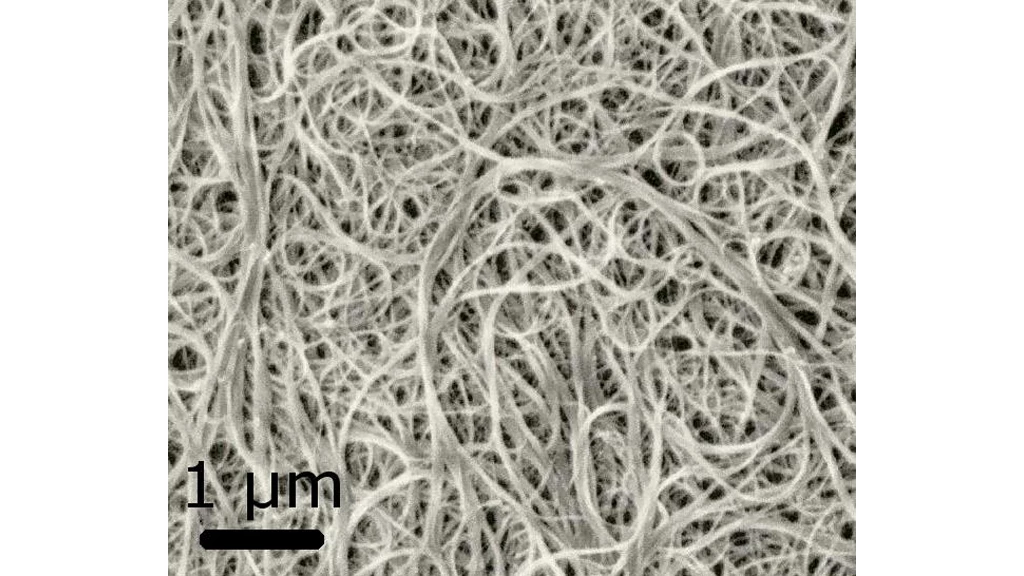

The technique developed by scientists at Rice University builds upon a 2003 Rice discovery of a way to dissolve large amounts of pure nanotubes in strong acidic solvents like sulfuric acid. The research team subsequently found that nanotubes in these solutions aligned themselves, like spaghetti in a package, to form liquid crystals that could be spun into monofilament fibers about the size of a human hair.

"That research established an industrially relevant process for nanotubes that was analogous to the methods used to create Kevlar from rodlike polymers, except for the acid not being a true solvent," said Wade Adams, director of the Smalley Institute and co-author of the new paper detailing the new technique. "The current research shows that we have a true solvent for nanotubes - chlorosulfonic acid - which is what we set out to find when we started this project nine years ago."

Following the 2003 breakthrough with acid solvents, the team methodically studied how nanotubes behaved in different types and concentrations of acids. By comparing and contrasting the behavior of nanotubes in acids with the literature on polymers and rodlike colloids, the team developed both the theoretical and practical tools that chemical firms will need to process nanotubes in bulk.

Industrial nanotube reactors today generate several tons of low-quality carbon nanotubes per year, and the worldwide market for nanotubes is expected to top $2 billion annually within the next decade.

But a final breakthrough remains before the true potential of high-quality carbon nanotubes can be realized. That's because all the methods of making high-end, "single-walled" nanotubes generate a hodgepodge of nanotubes with different diameters, lengths and molecular structures. Scientists worldwide are scrambling to find a process that will generate just one kind of nanotube in bulk, like the best-conducting metallic varieties, for instance.

"One good thing about the process that we have right now is that if anybody could give us one gram of pure metallic nanotubes, we could give them one gram of fiber within a few days," said Matteo Pasquali, a paper co-author and professor in chemical and biomolecular engineering and in chemistry at Rice University.

The paper, True solutions of single-walled carbon nanotubes for assembly into macroscopic materials, can be found in the Journal Nature Nanotechnology.