In the final part of our extended chat, the CEO and co-founder of Triton Submarines takes us through some highlight dives from an extraordinary career, from salvaging the "smoking gun" from the Challenger space shuttle and filming with James Cameron, to the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

In part 1, Patrick Lahey took us through his early years as a commercial diver, and the lightning-bolt moment when he got the chance to pilot his first submarine. He also discussed the OceanGate bombshell earlier this year, in which the entirely preventable death of a cowboy operator and his unfortunate passengers sent shockwaves around the world.

In part 2, he took us through the difficult birth of his own company, Triton Submarines, detailing what it took to gain the trust of his first customer, and the boundary-pushing innovations that make Triton's personal submarines stand apart to this day.

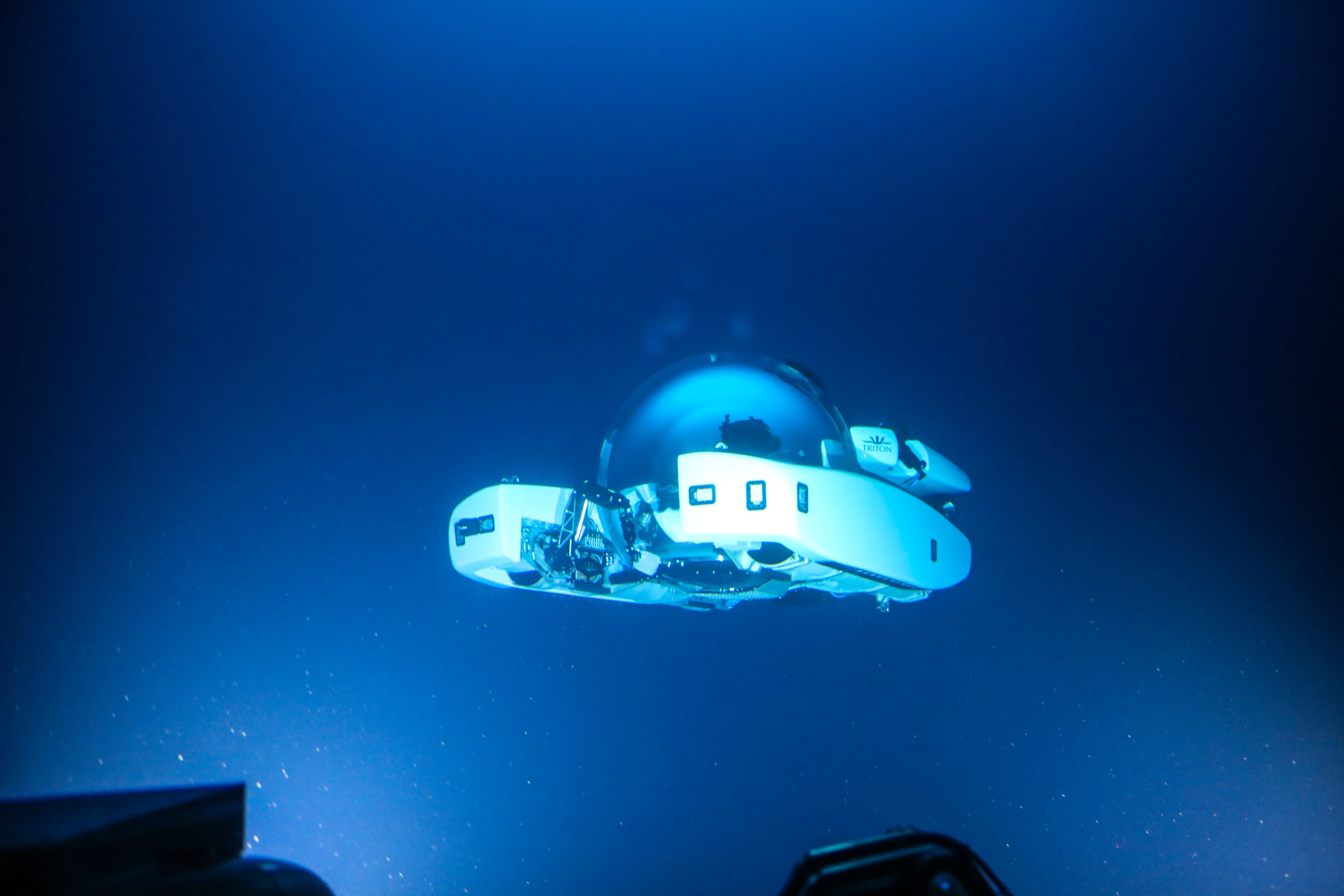

Now, if you'll forgive the unforgivable, it's time for a deep dive into some of the most memorable experiences Lahey has enjoyed in his own submarines, including the astonishing titanium-hulled Triton 36000/2, which regularly travels to the deepest points in the oceans.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation, in his own words.

Memorable dives from a remarkable career

Most memorable dives! That's a hard thing for me to sum up ... All my answers are long winded, though you're probably getting used to that by now! But yeah, I have been really fortunate in my life to have had some really extraordinary diving experiences. And most of those have been in subs.

I think one of the early ones would have to be diving on the space shuttle Challenger in 1986, and recovering pieces of the shuttle off the east coast of Florida here with Harbor Branch. Those ones I'm never going to forget. They were very sad, because you're recovering pieces of this machine that seven people died in, but it was one of the largest salvage efforts ever mounted. And to be part of that was ... I felt privileged to be out there. Even though when you'd see the pieces, you know, you felt awful.

We recovered the part that was the cause of the accident. The smoking gun, you know, the tongue and clevis joint that failed. It was pretty thrilling to be in the sub when that piece was found. So that was memorable.

I think the dives that I did when I worked for James Cameron were pretty interesting. We did some really interesting dives where we were diving four subs together. The two Russian Mirs and the two Deep Rovers were diving on these hydrothermal vents in the North Atlantic, all in a big area that almost looked like a movie set, even though it was a natural site. And these hydrothermal vents are really remarkable to see.

The two Russian Mirs dived always as a pair, and the two subs that Jim owned at that time also dived as a pair. His primary reason diving them in pairs is you can have one sub filming, while the other one was kind of in the action, if you will. So one that he called the film ship and one that was like, a subject ship or a lighting ship.

I was in the film ship with Jim, and he was, you know, filming. "We're painting it now!" Just a fantastically interesting individual.

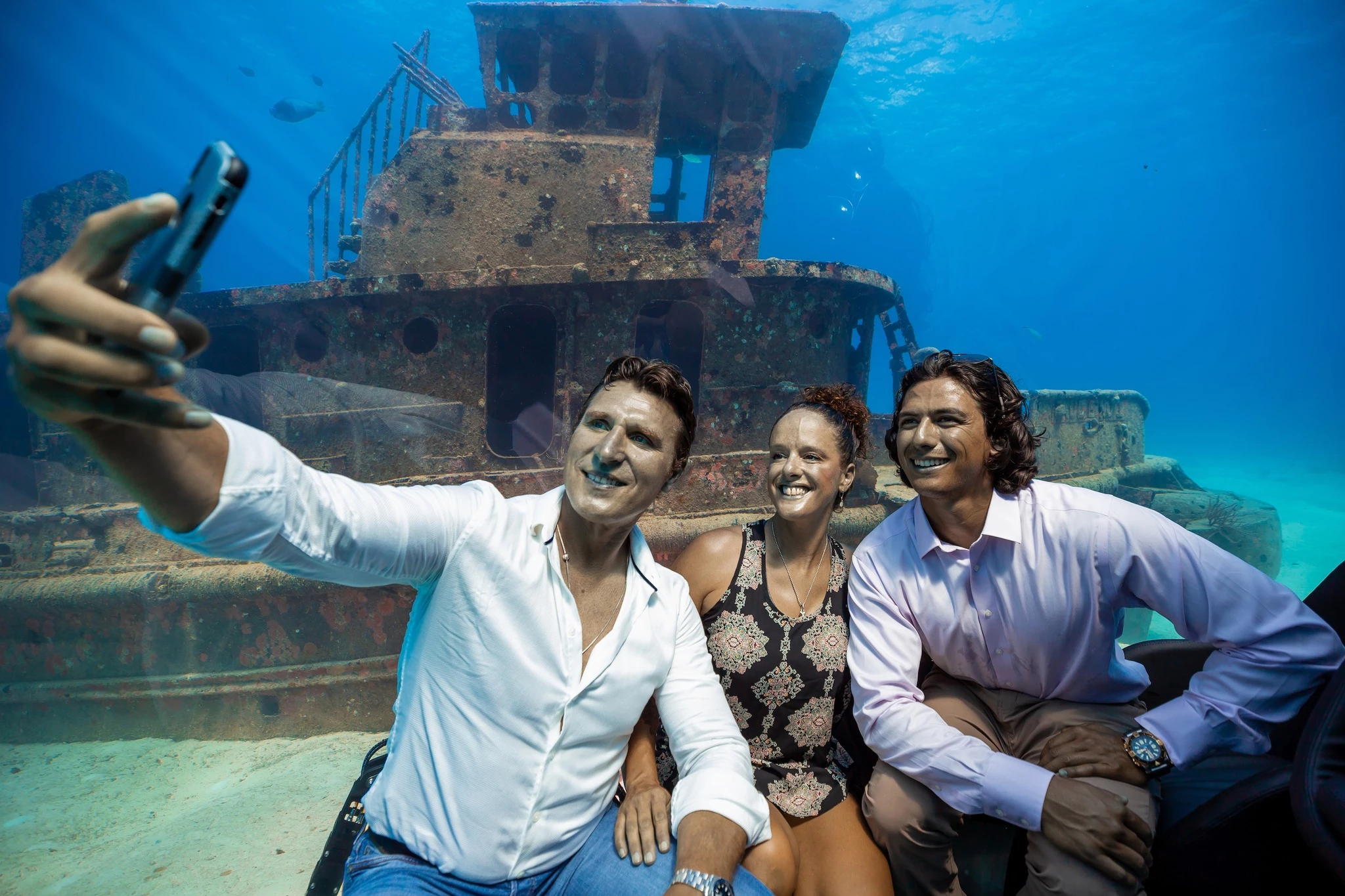

I'm sure I'm gonna forget some really good ones here. But in the early days of Triton we we did some really neat stuff. When Ray Dalio purchased his first sub from us we went and did a documentary about deep sea sharks. So we filmed some really fantastic stuff in Sagami Bay, Japan, as part of that documentary. And we proceeded south and we were involved in the filming of the giant squid. First time the giant squid had ever been captured and filmed in its natural environment. This was about 2011, 2012, I think.

I didn't know anything about biofluorescence. I mean, I'm not a scientist. I'm just a hardhat diver, you know.

Then I think around 2015, we did some really interesting dives in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, where we were filming bioluminescence and biofluorescence. Those dives kind of blew my mind. I didn't know anything about biofluorescence. I mean, I'm not a scientist. I'm just a hardhat diver, you know. So being in these subs, and we started putting on these yellow goggles and we had these blue lights ... We were down filming with the American Museum of Natural History.

And we switched on the blue lights and put on the yellow goggles. And all of a sudden, there was all this green shit all over the reef, there were these animals that were biofluorescing. I mean, stuff that if you took your goggles off, you know, wasn't there, but when you put them on it was there. Almost like, I don't know, a magic trick or something. But you suddenly realize there's a whole bunch of animals out there that are there, but you don't see them. And that was pretty interesting.

We also did this super cool dive that really left another indelible impression, we were doing a thing called a vertical transect, where you go to the bottom, and then you come up incrementally. And the idea was to capture this vertical migration that you've probably heard about, you know, where the animals migrate from the deep sea up to the surface at night. And then they go from the surface back down to the deep sea in the day.

And so, we're down there diving in the darkness, we started at 1,000 meters (3,281 ft), and then we come up in 100-meter (328-ft) increments, in the hope that you're going to capture this vertical migration as it's happening. And at 700 meters (2,297 ft), we were going up in darkness, and then you close your eyes, and then you set off these powerful strobes.

Everywhere you looked, in all directions, the entire water column was lit up with these biofluorescent or bioluminescent animals.

And boom, at 700 meters, it lit up these creatures all around us in the water column and all directions. It's hard to describe how incredible it was to see it. It underscores why you need human-occupied vehicles, because I don't know that there's an imaging system in existence that could capture the scope of that.

Everywhere you looked, in all directions, the entire water column was lit up with these biofluorescent or bioluminescent animals. I had two scientists in the sub with me and I remember them saying "f*****ck, look at this!" Here's these PhD scientists, just losing their minds. And I took a flashlight and I clicked a flashlight a couple of times, and off in the distance, another animal flashback the same number of times that I did at the same kind of frequency. The two scientists say, "did you f*cking see that?"

And on the way up, you know, we're getting near the surface, and there's scientists up there, they were capturing these things called flashlight fish. They literally have like a light organ, below their eye, that looks just like somebody stuck a f*ckin' LED there. I'm not kidding. Check it out. I could be wrong. I'm not a biologist. Full disclosure here! But all I know is I got a picture of one of these things and it's just sitting in the palm of my hand, and it's got this oval shaped feature on its face. And those give off light.

And so we were coming up the wall, and we looked up and like tens of thousands of these things are coming over the wall. And their light organs are all lit up, and it's just like ... it's like fireworks. It's the only way I could describe it. You ever been to Scotland and watch the tattoo from the Edinburgh Castle? Well, they do this thing where they have these fireworks that bore down the f*ckin' wall. That's what it looks like. It was awesome.

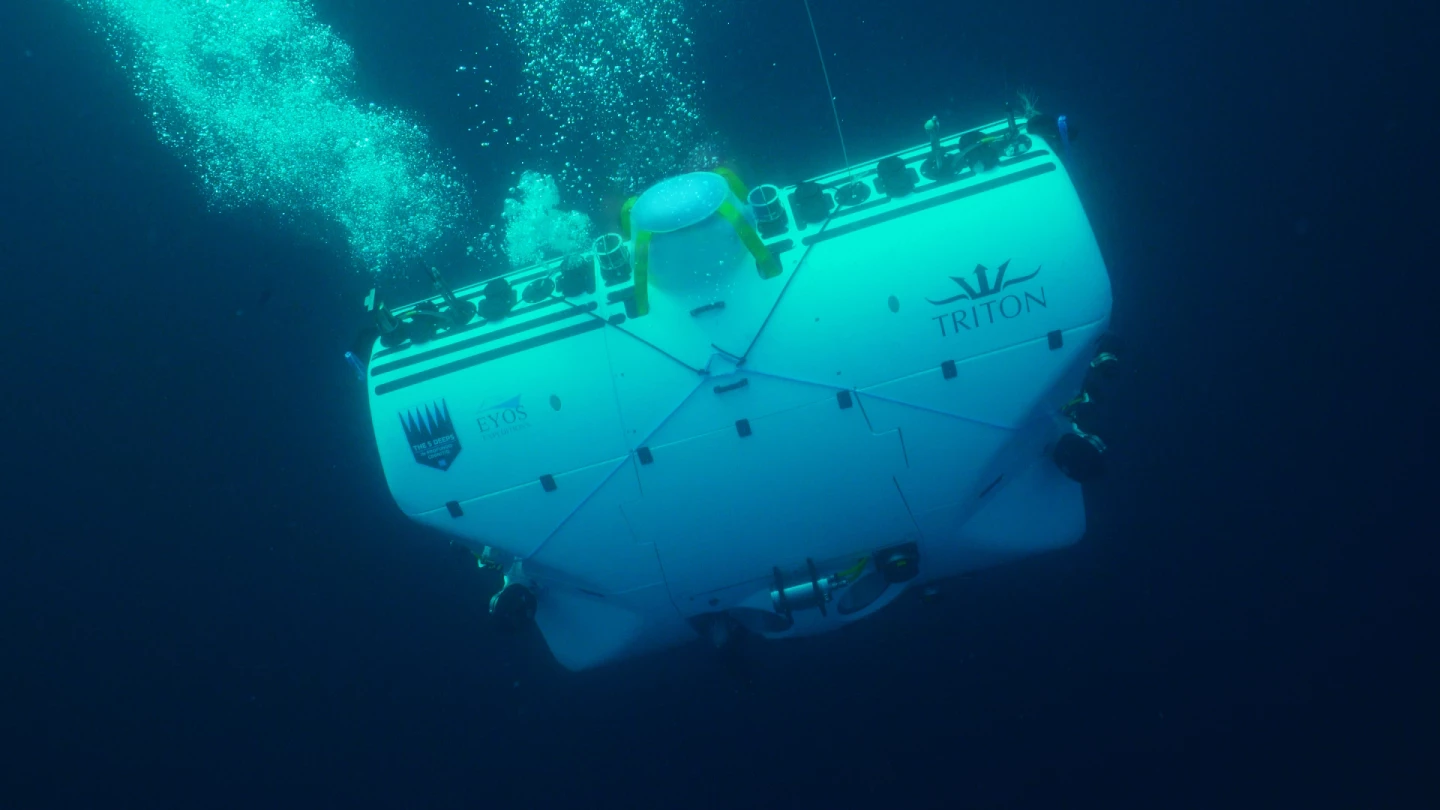

And then of course, you know, the dives that we did recently on the Five Deeps expedition and the opportunity to be part of that historic mission where we built the deepest diving sub in the world – and a sub that has now made 20 dives to full ocean depth – the Triton 36,000/2. Building that sub was really the realization of a dream for me, and a chance to be part of something much bigger than I could have ever imagined.

We still use acrylic but we have only three windows which are spherical sector viewports – one for the pilot, one for the copilot, one that they share, you know, because you can't use acrylic in a full ocean-depth-rated sub. The pressures are just beyond what the material is capable of managing. You're talking like 16,000 psi, or 1,100 bar.

It would take 292 fully fueled 747s, sitting on top of the pressure hull of the Triton 36,000/2, to equal the pressure that it's under in the Mariana Trench.

If you were to take a 747, which weighs I think three quarters of million pounds fully fueled, it would take 292 fully fueled 747s, sitting on top of the pressure hull of the Triton 36,000/2, to equal the pressure that it's under in the Mariana Trench. Imagine the Eiffel Tower on your big toe, that kind of thing.

The way Five Deeps started was, you know, Victor had this audacious goal, wanting to dive to the deepest point in each of the five oceans, so he calls us up and said, you know, can you guys build me a submarine that can dive to the deepest point in the ocean? Of course, I immediately said yes. Without really having an idea of how we're going to do it or whatever. But interestingly, we'd been thinking about that for probably about eight years before he reached out to us.

We wanted to build a sub with a glass hull, because, of course, I value that transparent viewing experience and recognize how much more powerful it is. But that wouldn't have worked. He came out with us, went for a dive in one of our Triton 3300/3s. I think he loved the experience, and decided to engage us. Initially, we did a design study and during the design study we came up with a plan for the vehicle we would build as well as a budget and a timeline. And after he saw that, and he greenlighted it, we could then build the vehicle.

But you know, I have the privilege and the good fortune to work with some incredibly smart, incredibly talented people. I do not consider myself to be among them, by the way. These guys are the ones that come up with these brilliant designs. And I think the only thing I bring to the table maybe is a lot of experience in operating subs. We did a year of design and engineering. Then we did two years and two months to build the vehicle. And then it took us 10 months to prosecute the expedition, when we finally got started in about November 2018.

Inside that crinkled, boxy looking shape – some people said it looks like a sewing machine, it's shaped that way to create a minimum amount of drag in the most important direction, which is the vertical direction. So it can travel through the water column very efficiently, when it's going to the dive depth and when it's returning from depth. So inside of that structure that you see, which is mostly syntactic foam, is a perfectly spherical titanium pressure boundary, that's 1,500 mm, or about 59 inches in inside diameter, and 90 mm or about three and a half inches thick.

It's really a perfect sphere, because it's two halves, that are bolted and clamped together through a mating ring, with no welding whatsoever. And the reason there's no welding is because welding introduces the possibility of changing the material characteristics of the titanium, which would create areas of high stress, or discontinuities, you know, that create areas of high stress.

So by bolting and clamping it together, which is again, another brilliant idea of one of engineers, you eliminate all of that. And you know, there's something really simple, but elegant about that option. Most everything else is welded, but there was no welding, it was just bolted and clamped together, which made it as close to a perfect sphere as you could probably ever achieve. I mean, effectively, it's just a giant f*ckin' ball bearing.

How much do these submarines cost?

A lot! That particular submarine was the most expensive sub we've ever built by quite a bit. It's a US$37-million-dollar submarine. Most of our subs, though, are are much more ... well, I'm not gonna say reasonably priced, but certainly a lot more affordable than that one! They're clustered in the kind of $4 to $8 million range. The outlier is the Triton 4000/2 Abyssal Explorer (previously known as the Triton 13,000/2 Titanic Explorer), which would be probably around $15 million.

But we haven't built one yet. It'll be amazing. I hope that somebody steps up. And by the way, all our subs start like that, as just renderings, and then you get somebody that's willing to say, "you know what, yeah, I'd like one of those," and then it becomes real. And just because it's a rendering, it doesn't mean that we haven't put a lot of thought into it. If we build one of those Triton 13,000/2s, it would look a lot like that. Probably almost identical to that. Because a lot of thought and engineering time has gone into creating it.

The way it'll let you see below your feet, that's really important, right? Spatial awareness, situational awareness, whatever you wanna call it, it's really an important part of safety. So if you want to build something that's safe, make sure the people who are in it can see.

Not to mention, if you want to make the experience profound and memorable, build a transparent hull and give people the best view possible. Because at the end of the day, a submersible is a visual tool. And the more compelling, the more powerful you can make that visual experience, the better we've done our job as submarine manufacturers.

What's it like diving to the deepest parts of the ocean?

The full ocean depth sub, the 36,000/2, it would take us four and a half hours to go from the surface to 11,000 meters, or 10,932 meters (35866 ft), and about three and a half hours to come back up. So, it's about an eight-hour round trip. And then, whatever time you spend on the bottom, which is typically no less than four hours ... So those dives would be 12 to 14 hours in duration.

I've actually made five dives to in the Marianas Trench. Super cool. I mean, for me, it was exhilarating. People ask me was I hesitant about going? F*ck hesitant! Are you kidding me? I couldn't wait to make that dive. Wild horses couldn't hold me back. It was something that I had dreamed of doing.

You know, I grew up reading about people like Don Walsh, and Picard. Don Walsh became a friend. Shortly after I went to high school, actually, I met him when I was in my early 20s. But, you know, he's really another great mentor. And somebody that is an inspiration to so many people, including me. I've been lucky had lots of great mentors. So, for me, the chance to make that dive was ... I mean it when I say it was a realization of a dream, you know, so it was just super cool.

My first dive was actually with a guy named Jonathan Struwe. He was the DNV surveyor from the certification agency, the people responsible for the accreditation of the sub. And this individual, as part of the accreditation process, has to validate that the sub can actually go to full ocean depth. So he climbs in the sub with me and we go to the bottom of the ocean. That's commitment right there, on his part. He could've said "hey, listen, take some pictures when you get there." But no, man, he f*ckin' jumped in and we made the dive together.

And it turns out, we ended up having to do a salvage at that depth too, because one of the landers was stuck in the mud. So together we went over, found the lander, pulled it out of the mud and sent it back to the surface. That was a pretty great friggin day.

Because not only do we do the certification dive and get the sub the first certificate they've ever issued that says "unlimited diving depth, any ocean." That was kind of cool. But also, we not only proved we could get to the bottom and come back up safely, we actually were capable of doing meaningful work on the bottom, we rescued this lander that was worth $400,000. It had a unique watch on it. The lander itself is worth a quarter million bucks. I think the watch was another 150k. So getting that thing and bringing it back to the surface was pretty friggin great.

After we recovered the lander, I looked over at him. And I look over at him and say "okay, Jonathan, is there anything else you want to see?" And he said, "you know what, I can't think of a friggin' thing." He wouldn't say friggin' though, because he's very polite, unlike me. He said, "I can't think of a thing." So we break out this apple strudel. And we both eat some apple strudel. And then I throw on Give Me Shelter by The Rolling Stones and pull the pin and we head back up to the surface.

So get this. Back in March, you might have heard about this. There was a shooting in Hamburg, Germany, at a church. Seven people were killed, four people seriously injured, and another four people, you know, badly injured. Jonathan Struwe was one of the people in that church. He was shot seven times, and survived. Just a further testament what to what an extraordinary human being this guy is. I don't know how the f*ck he survived, but he did.

We have a really creative group of people involved in the development of our subs. And we've managed to create some pretty interesting, innovative, exciting, new designs. And we're not done yet. I'm going to keep doing it. Because I love it.

And we need more of it, frankly, because I think it's a part of our world that we've kind of neglected. Honestly, I don't think we've ever given the ocean the attention that it deserves, and that's warranted. There's so much for us still to do in the ocean space.

And I know that everybody is very enamored by what's happening in space. And, you know, the idea of taking off in rockets and finding new planets, and all that sort of stuff, it's wonderful and very exciting. But frankly, I think we need to devote a lot more time, energy and resources to ocean exploration and to learn more about the most significant, most important feature of our own planet. I'm encouraged by the progress that we've made in the last 10 years in particular, but there's still a lot more that we could and should be doing.

There's so much of it that we haven't actually visited or studied or even seen. So the idea of building more subs and giving more organizations, more entities, more people, access to those subs is something I'd like to see happen. I don't know if we ever will, because they're expensive.

And the resources that people seem willing to direct towards the ocean are a fraction of what we lavish on space exploration. I'm not sure what accounts for the disparity, honestly. You know, why there's this fascination with space? I think I have some ideas and I've often shared those with others. I think it's that when you look at the ocean, you know, it's harder to imagine things than it is when you look up into the sky.

But space is mainly space, and there's a hell of a lot going on under the surface [of the ocean]. And I suppose that's why common sense would dictate that we should start directing more of our time and energy at the ocean. It's no secret that we're heavily dependent on the ocean, which supplies most of our oxygen and controls our climate. It's a carbon sink, it's by far the most beautiful place in the world, as far as I'm concerned. So yeah, I think it would be great if we spent more time on it. It's a lot cheaper than going to space, as well.

A friend of mine, Grant Gilmore, is an ichthyologist that lives here in Florida. And I remember him telling me once years ago that a single space shuttle launch would provide the budget for the oceans for eight years. The full budget for ocean science for 80 years as well, something like that? It's kind of a staggering statistic. And I don't know whether it's relevant anymore, but it's probably even more skewed towards space now than it ever was.

The resources that people seem willing to direct towards the ocean are a fraction of what we lavish on space exploration.

But what's encouraging to me – and I like to think of the encouraging things because, as my customer Victor Vescovo is fond of telling me I am a relentless optimist – what's encouraging to me is seeing people like Ray Dalio, James Cameron, people like the Schmidt family ... There's a number of individuals who have become keenly interested in funding ocean science related projects, and it's great to see that happening because we need people with that pioneering spirit to underwrite these ambitious kind of undertakings.

Victor Vescovo is another example. His program, while it wasn't focused entirely on science, it had a legitimate, very important science component to it. And you know, frankly, that stuff that we did during the five deeps expedition – we traveled 50,000 nautical miles and we took 400,000 samples and mapped three quarters of a million square kilometers of deep ocean at a level of accuracy that's never been done before. That's great stuff. We need more of it.

Be sure to check out parts one and two of this interview if you haven't already. Thanks to Patrick Lahey, Tatiana Maravich, Kelly Downey and Sharon Wolfe for their assistance on this story.

Source: Triton Submarines