It takes guts to start a company. It takes a lot more guts to start a company manufacturing cutting-edge private submarines. And as Triton's CEO and co-founder explains, it takes even more guts to slap down your money and become the first customer.

In part 1 of our three-part interview with Patrick Lahey, we learned about his early days as a commercial diver, and the career-shattering revelation he experienced the first time he jumped in one of the Mantis submersibles Graham Hawkes was building in the 1980s and 90s. If you're looking for his thoughts on the recent OceanGate Titan disaster, check out part 1.

In part 2, Lahey takes us through the beginning of Triton Submarines, from its conception, to 12 years later, when his first client placed millions of dollars – and his life – in Lahey's hands to order the company's first submarine.

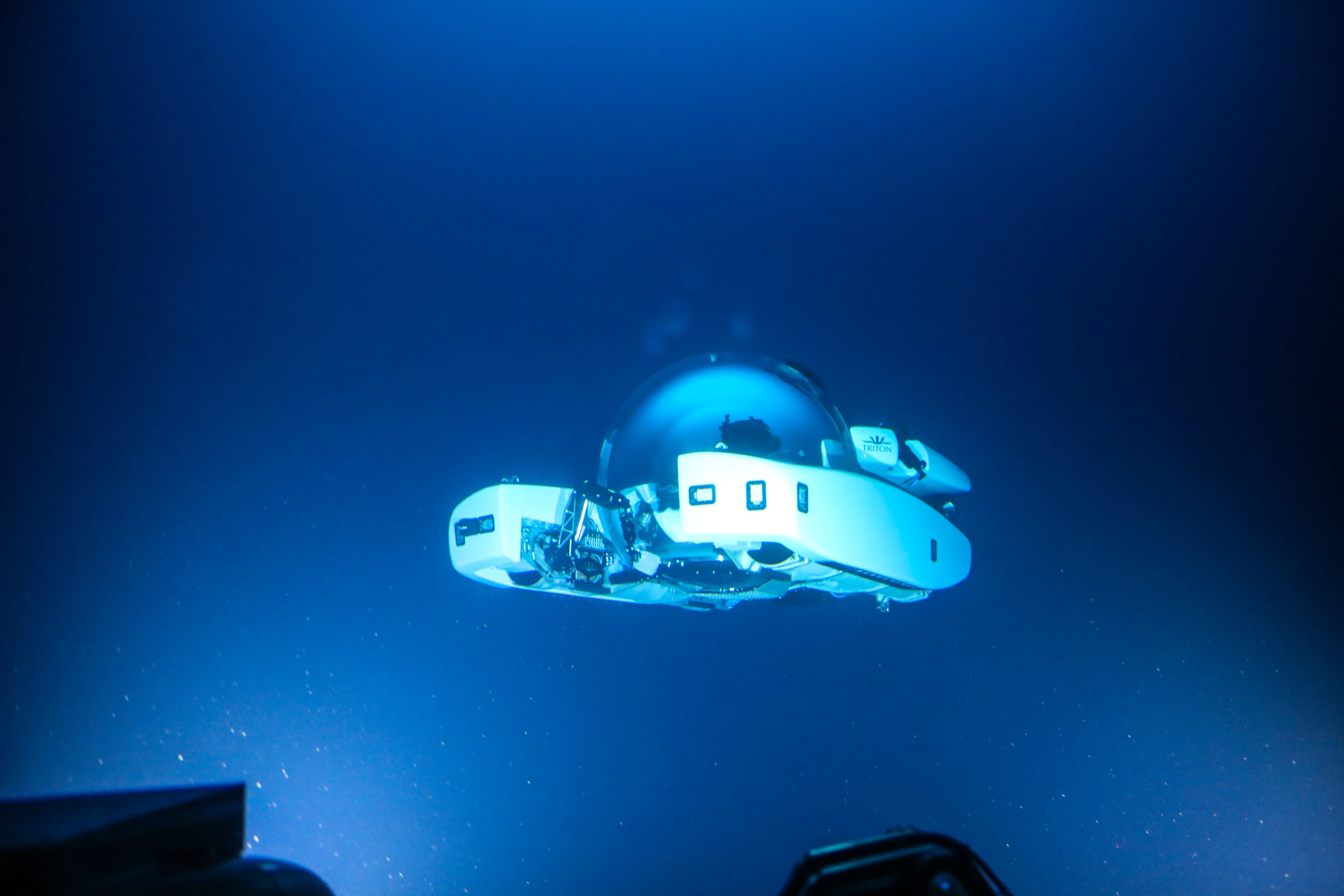

He speaks about the groundbreaking acrylic bubble hulls that have defined many of the company's builds, and that will, if OceanGate hasn't destroyed the market for everyone, eventually form the transparent pressure hull of Triton's upcoming 4000/2 Abyssal Explorer (previously known as the Triton 13000/2 Titanic Explorer).

What follows is an edited transcript, in Lahey's own words.

A difficult birth: starting a new submarine company

For years, I operated subs for different people in different capacities. Whether it was oil and gas, or filmmaking, or science or salvage, a lot of different disciplines. And then I went to work for a company called Atlantis Submarines for about seven or eight years, building their subs.

I think I just got this idea in my head that I could build a better sub. I found myself making excuses for the things that weren't right with them, and just knowing I could build something that might be better. And I just became fixated on this idea: wouldn't it be cool if you could build your own sub?

And I met my former business partner, Bruce Jones, in around '94, I was actually doing an Atlantis Submarine build in Everett, Washington. I'd read some kind of a newsletter that Bruce had written, which kind of resonated with me, so I just picked up the phone and called him and he invited me to meet him at his house. We started talking about the idea that, hey, maybe we could build our own subs.

It took a while for it to happen. Wasn't until about 12 years later that we actually got the opportunity to build our own sub. So it wasn't a quick thing, didn't happen overnight or anything. And there was a lot of frustration ... I think when we started telling people "hey, we can build a submarine for you," they probably thought we were a little bit crazy. People wouldn't take us seriously.

It wasn't until 2006 that We met Chris Cline, our very first customer. And he took a chance that we weren't crazy. I had some sketches of the sub that we wanted to build for him. And he looked at me and kind of sized me up. He said "can you really do this?" And I said yeah, we can do it.

And he asked someone else he had on a call, turned out to be Jim McFarlane from ISC. And Jim said "listen, if Patrick tells you he can do it, he can do it." I don't know if that's what did it, but for whatever reason, he gave us a chance to build the sub. And that's really what got the ball rolling for Triton Submarines.

Chris, unfortunately, died in a helicopter crash about four or five years ago, just a brilliant human being and a visionary. And somebody that was willing to break with the pack and do something different. If it hadn't been for Chris Cline ... He definitely was instrumental. Not just in placing that first order, but in fundamentally changing the conversation.

Because now Chris had one of these things on the back of his yacht, Mine Games, and he was so proud of that sub sitting on the back of his boat. And it created a lot of buzz, a lot of excitement. And I think when Chris started speaking enthusiastically about the really cool dives that he was doing, that's what shifted things. That's what changed the conversation. So I'll always be deeply grateful to Chris, for his willingness to give us a chance.

The sub that we sold Chris on was originally called the Triton 650, because it was going to be good for 200 meters (656 ft), with a metal back end and an acrylic front end. But we eventually turned it into the Triton 1000/2, which was a completely transparent acrylic sphere, that would go to 305 meters or, 1,000 feet.

It's a simple looking kind of a sub today – coincidentally, it's in my shop right now, the very first sub we built is still in service, still being used by a new owner. When I look at it, it's kind of like an MG Midget. It's very simple, but there's something wonderfully elegant about the simplicity of it.

A little two man sub, 1,000-ft depth. I think it was really where the company's founding principles were created, you know, this idea of simple to operate, easy to maintain, reliable, safe, fun, all that sort of stuff. That sub was the start of it all. And I think the fact that it's still around 17 years later, and still in great shape, and still in the hands of a client that we have a great relationship with, that speaks volumes about the company, our commitment to the products that we build, the efficacy and the reliability of the things we built in the early days.

We built two of those. We never built anymore two-person subs. I thought mistakenly, by the way, that everybody would want a two-person. Like, if you're going to buy a Lamborghini or a Ferrari, you're not going to hire a chauffeur to drive you around, you're going to drive the goddamned Ferrari or Lamborghini yourself, right?

I was grossly mistaken, our customers weren't actually interested in operating the subs themselves.

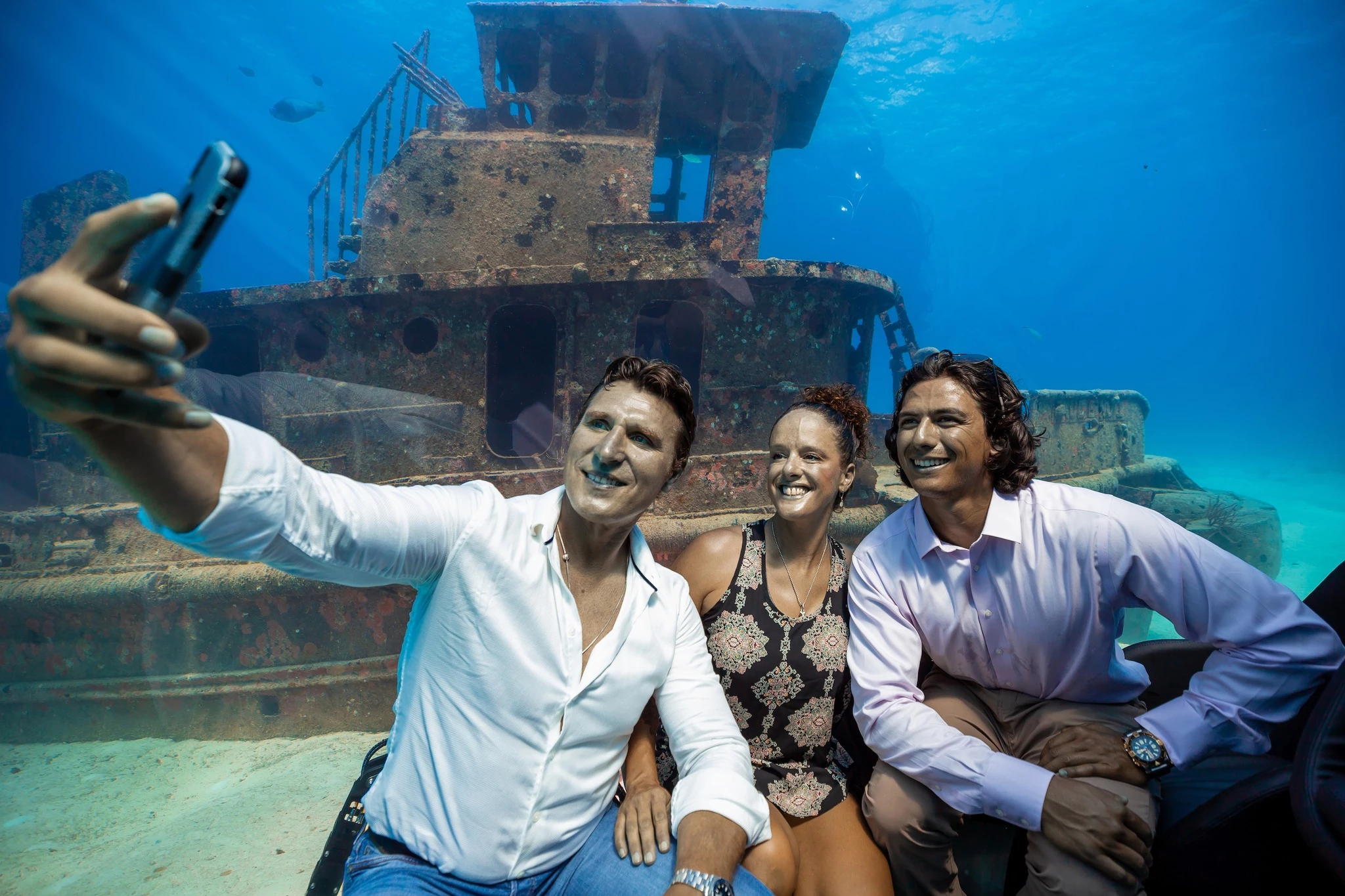

But I was grossly mistaken, our customers weren't actually interested in operating the subs themselves, they were more interested in enjoying the experience with somebody else, which is why virtually all of the subs that we've built since – not all of them, but most of them – have been three people or more.

You got a professionally trained pilot that knows the vehicle, understands the procedures and everything else. And you can just sit there and enjoy it with your wife or your girlfriend, being able to share the experience with someone else, and not worry about how to operate and maintain it.

Honestly, you know, it'd be great to say you have to be super brilliant to do it, but it's really super easy. When I say they're simple to operate, I mean it, they really are very intuitive. And they have to be; we realized that the market we're selling to would be intolerant of anything that wasn't simple, and reliable, and safe. So just by necessity, we had to build stuff that worked well, and was reliable. Because if it wasn't, they'd kick it off the boat.

At this point, we're closing in on around 25 vehicles, so it's not a huge number. People think, shit, 25 submarines in 16, 17 years, but it started out very slowly. We built the first one in 2006, delivered it in like 2007, another one in 2007, delivered in 2009. So it was really slow to begin with. And we also had to overcome a technical challenge in the early days of the company that threatened to put us out of business: the reliable production of acrylic.

And until we solved that problem and created a new methodology for producing the acrylic that we use in our products, we would have never been able to do the things that we've done since. As of today, we're now going to be consistently building three, four, maybe even up to six subs a year.

So you're gonna see a dramatic uptick in our volume, if we can continue to manage the production. But yeah, the cat's out of the bag. People's perception of these things as dangerous and scary and complicated, that's changed. And now people are far more receptive to the idea of buying a sub and putting it on a motor yacht.

But I can tell you, initially, there was a lot of skepticism and a lot of pushback, because people thought that if you got in one of these things there was a better than average chance you weren't gonna get back out of it alive.

If you watch, every film you'd associate with a submersible is a disaster, you know, people choking to death and being depth charged and all that. It's something that is certainly an impediment to us making sales because people are afraid of these things. They think, Oh, my God, this thing must be really frightening and dangerous, and wickedly complicated and all that. It's taken us a while to break down those barriers, and demonstrate to people that they really are simple. They really are fun and exciting and safe.

It's really only in the last five to seven years that people have really begun to embrace the idea of a sub on a yacht. And I can tell you this seachange moment was clear at boat shows about seven years ago, when the yacht manufacturers that were laughing at us when we came to talk to them suddenly turned around and started coming to us. Their customers were wanting subs on their yachts, and they needed us to show them how to do it.

If you watch, every film you'd associate with a submersible is a disaster, you know, people choking to death and being depth charged and all that.

It's not that complicated, but you can imagine, if you want to put a sub on a yacht, it's something that requires some thought and planning. The subs are heavy. You need cranes or gantries, or lifting platforms to put them in and out of the water. And that requires a foundation. You need support equipment. You need compressors to create the high pressure that you need. You need oxygen storage for life support and other things. So you can imagine that if you're building a boat that you want to put a sub on, it's a whole lot easier to do that if you've planned for it when the vessel is being conceived, rather than trying to do it as an afterthought.

The key innovation: Acrylic pressure hulls

But yes, one thing nearly sank us. We were pushing up against the limits of what was possible in those days with traditional acrylic manufacturing. When we first began trading, the only way to produce acrylic spheres for subs was using a methodology called slush casting where they take liquid acrylic and solid bits of acrylic, and they put them into a mold. And then they they take that mold, and they vacuum it down and they anneal it in an autoclave.

Back around 2011, the vendors weren't able to deliver the acrylic because we were trying to produce a sphere that was thicker and bigger than anybody had ever made before. And they were encountering real difficulty with that, in fact, such difficulty that I had orders I couldn't fill. And the fact that I couldn't fill those orders threatened to put us out of business.

And so realizing that we were in trouble, I went over to Germany and met with the people who invented acrylic. This is a company that used to be called Rohm & Haas. They actually invented it pre World War Two. Haas was Jewish, so he fled to the United States and started producing it as Plexiglass. Rohm was producing acrylic back in Germany under the name Acrylite – same material, PMMA, polymethyl methacrylate. That's the material that's used in all our subs.

[Röhm has since been in touch to clarify the history here: "Dr. Otto Röhm was producing acrylic in Germany under the trademark PLEXIGLAS® since he registered brand in 1933. The brand PLEXIGLAS® belongs since August 2019 to Röhm GmbH Germany. And the sister brand for the same PMMA products in America is ACRYLITE®, which was registered in 1976 and now belongs to Roehm America LLC."]

When you submerge in a sub with a crush pressure hull made of acrylic, it's almost like it disappears when you submerge.

Acrylic is a wonderful material. It's strong, it's malleable, it's a perfect insulator. It has a really interesting characteristic in that it has the same refractive index as water. So if you take acrylic and you submerge it in water, it appears to vanish. You can't tell where the water begins and the acrylic begins. And that's one of the things that makes diving in a sub with an acrylic pressure boundary so compelling – because it's a very immersive experience.

When you submerge in a sub with a crush pressure hull made of acrylic, it's almost like it disappears when you submerge. It's almost like there's nothing between you and the environment that's around you. And that really makes it emotionally powerful. I mean, you just feel like you're right there, you could touch the fish, they could swim into the cabin.

The challenge that we encountered was the physical limitations of acrylic manufacturing using slush casting, but these guys in Germany, I figured if anybody could figure out a better way to do it, they could. So we went there and met these guys, their company was called Evonik at the time, outside Frankfurt.

And I asked them if they could produce spheres for us. And they said "well, we've never produced spheres, we've done flat windows, we've done spherical sector windows. But we've never done anything as big as as a sphere. But we think we could do it. We're going to have to do a design study, it'll take about two years."

So they embarked on this design study to prove that they could produce these acrylic spheres using what's called thermoforming, where you take acrylic, which is produced in these big flat sheets that are six meters long and three meters wide (20 x 10 ft), and they cut a disc out of the block. And then they take that block, and they put it in an autoclave, and they can form it into a hemisphere. And then they can machine it, polish it, bond it and produce spheres. And after two years, they confirmed that yes, they could do this, they accepted our order. And they produced the first ever thermoformed acrylic pressure boundary.

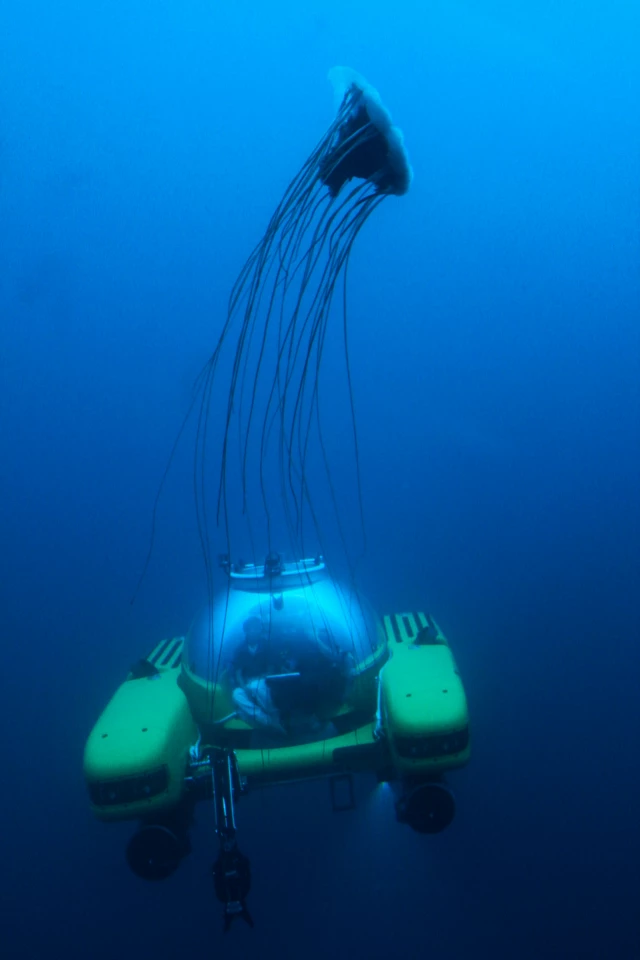

That was for a sub called the Triton 3300/3. So a sub that goes to 1,000 meters (3,280 ft), and carries three people. Our nomenclature is just diving depth in feet, slash number of people.

But we didn't realize the significance of this move until later, when we realized that with thermoforming, we could build much bigger, much thicker acrylic spheres. And there was an added benefit: because we weren't slush casting the spheres, the acrylic material is about 20% stronger. So we can build better, stronger, clearer spheres. They didn't have the chemicals added to it, the crosslinking agents, so you could bond it more effectively, you could reduce the thickness of the bonded joints. And as a consequence of that development, we've been able to produce a whole range of interesting subs that can go deeper.

The thickest one we've built was for Project Rev Ocean, and that's has a pressure hull that's 324 mm (12.7 in) thick. It'll carry three people and dive to 7,500 feet, or 2,300 meters. Completely unprecedented. We produced that sphere just a few years ago, just to illustrate how far we've come, the 3300/3 was the largest and thickest acrylic sphere ever made when it was built. Now, we produce a sphere that's twice that thickness.

The 3300/3 was the largest and thickest acrylic sphere ever made when it was built. Now, we produce a sphere that's twice that thickness.

The halves stick together with glue. It's a pretty good glue, though. The glue joint is actually stronger than the parent material. So it's not as though it's an inferior or a weak area, an area of high stress or anything like that – the bonded joints are incredibly strong. And they're so thin. In the early days, I remember being in subs where the bonded joints were three quarters of an inch thick.

And they weren't thermoformed, so they looked like a soccer ball, made up of fused pentagons, little pieces of acrylic that were all glued together like a jigsaw puzzle. But now those bonded joints are almost invisible. I mean, if you're looking right at them, you can see them. But if you get five or 10 degrees away from it, it disappears, you can't see it.

They've come so far, we can now produce spheres that are so big, the early spheres that we thought were so incredible in 2013, you could put one of those inside the spheres we're building now. We're building subs that will carry seven people and go to 1,650 feet, a Triton 1650/7 – or six people and go to 1,000 meters, 3300/6.

All of that was made possible by those pioneering efforts of the German vendors that produce our acrylic spheres. For whatever reason, this multi-billion-dollar company Rohm kind of took up the technical challenge of producing these spheres. And I'll tell you something, if they hadn't taken an interest, Triton probably wouldn't exist today. So it was really thanks to them. It's probably only a tiny fraction of their business, we're like the gnat on the elephant's ass. They did it because they were passionately interested in the engineering challenge.

Now, we can even produce a sphere that would be 450 mm (17.7 in) thick, and go to 4,000 m, 13,000 ft. That's our Triton 4000/2 Abyssal Explorer [previously known as the 13000/2 Titanic Explorer], which is our deepest diving acrylic sub. And then, as you correctly pointed out, the other interesting thing is now, we have elliptical shaped pressure boundaries. And those are a complete departure from convention. In fact, not only are they a complete departure, they don't even fit within the standard PVHO guidelines (pressure vessels for human occupancy).

One of our engineers came up with this clever idea about using an elliptical shape. And the reason that it's such an inspired idea is because it will allow us to carry more people in a smaller volume. Subs are displacement vehicles. So the bigger and more comfortable they are, the more they displace. The more they displace, the heavier they are. The heavier they are, the more difficult they are to manage. So the idea behind the elliptical hull is people can sit down in it, and stretch out and be comfortable, have a great view, but there's not a lot of wasted volume.

And the wasted volume adds to crane weight. So when you can use the volume more efficiently, you can reduce the overall weight of the vehicle. So we can now produce a sub that will carry nine people, a pilot and eight passengers, that only weighs about 12 tonnes. So that's huge. And it's opened up another interesting potential market for our products, notably the cruise ship industry, where a cruise ship can handle a relatively small, modest sub that weighs 12 tons, but it can carry nine people and eight guests.

The idea of a sub that can take that many people and make multiple dives every day is really pretty exciting. You know, if you go to one of these great locations – Galapagos, Antarctica – the idea of being able to climb in a submarine and go and see what's underwater is really appealing. And not only does it appeal to the guests on the ship, it appeals to the people that own the ships, because they want to create memorable experiences for their guests.

That's the Triton 660/9 AVA. We're building the first two of those right now. We haven't delivered it yet. The first one is being delivered in October this year, to a company called Scenic. They operate a really extraordinary six-star cruise ship vessel that only takes 150 - 200 guests. So you're dealing with smaller numbers of people that are focused on expeditions, they want to go and have interesting, exciting experiences. They don't just want to go to Cancun and Jamaica, they want to go to more exotic and more interesting, more exciting places.

Stay tuned for part 3, coming soon, in which we'll follow Lahey as far down as it's possible to go, on some of his most memorable dives. Triton's 36000/2 would become the first submersible in history certified for any depth, in any ocean, an express elevator that can take two people to the bottom of the Mariana Trench in four hours, then up again in three and a half.

Source: Triton Submarines