Fraunhofer scientists have used ultra-thin diamond membranes to drastically cool electronic components and boost electric vehicle charging speeds, taking advantages of diamond's excellent thermal conductivity..

Heat is usually an unfortunate side effect of electricity, and too much of it can damage components and devices, sometimes in dangerous ways. As such, managing and removing heat is a major consideration in electronics design, with heat sinks usually made of copper or aluminum. The problem is, these metals are also good conductors of electricity, so another insulating layer is usually needed. So for the new study, the Fraunhofer team turned to diamond, which is an excellent conductor of heat but an insulator for electricity.

“We want to replace this intermediate layer with our diamond nanomembrane, which is extremely effective at transferring heat to the copper, as diamond can be processed into conductive paths,” said Matthias Mühle, a scientist on the project. “As our membrane is flexible and free-standing, it can be positioned anywhere on the component or the copper or integrated directly into the cooling circuit.”

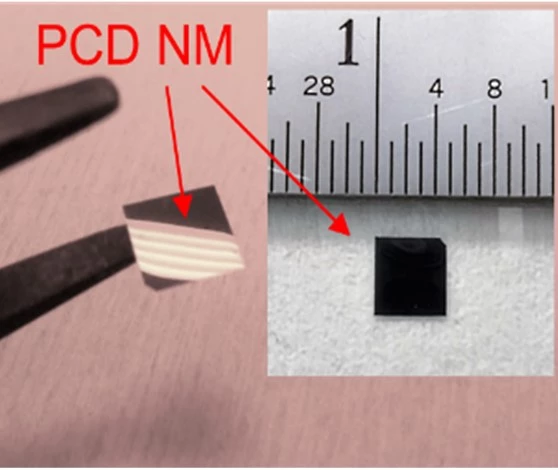

Diamond heat spreaders are already starting to find use, but these are usually more than 2 mm thick, and can be tough to attach to components. The nanomembranes, however, are just a micrometer thick, flexible and can be bonded to electronic components by gently heating them to 80 °C (176 °F). The team manufactured the nanomembranes by growing polycrystalline diamond on top of silicon wafers, then detaching and etching the diamond layers.

The researchers estimate that the diamond nanomembranes could reduce the heat load of electronic components by a factor of 10, which would of course boost the energy efficiency and service life of those components and the overall device. If it was incorporated into charging systems, the team says that the membranes could help boost charging speeds for electric vehicles by five times.

Maybe best of all is that because the diamond nanomembranes can be made on silicon wafers, the manufacturing process should be relatively easy to scale up for industrial use. The team has already filed a patent for the technology, and plans to start testing it later this year in inverters and transformers in electric vehicles and telecommunications.

Source: Fraunhofer