Utilizing a recently developed brain imaging technique new research suggests that measuring accumulated levels of a protein called tau may predict future neurodegeneration associated with Alzihemer’s disease. The discovery promises to accelerate clinical trial research offering a novel way to predict the progression of the disease before major symptoms appear.

Exactly what occurs in the human brain during the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease remains quite a mystery for dementia researchers. While studies have homed in on several pathological signs signaling moderate to severe cases of Alzheimer’s, it’s still unclear what the initial triggers for the disease are, and without this vital information scientists are struggling to generate effective drugs and treatments to slow or prevent the disease.

The two big pathological signs of Alzheimer’s most researchers agree on are accumulations of amyloid and tau proteins in the brain. Abnormal aggregations of amyloid proteins, into what are referred to as plaques, are generally considered to be the primary causative mechanism behind Alzheimer’s. Masses of misfolding tau proteins, forming what are known as neurofibrillary tangles, are also seen in the disease.

So what comes first? The amyloid plaques or the tau tangles?

This question has been the source of great debate amongst researchers for a number of years. The overriding consensus has been amyloid aggregations come before the tau tangles. One researcher even used the analogy of tau being a bullet, but amyloid is the trigger, with its plaques activating the conversion of tau to a toxic state.

Following years of failed clinical trials into drugs targeting these amyloid and tau aggregations a growing community of researchers is looking further afield for potential undiscovered causal mechanisms behind Alzheimer’s. But the association between these two protein build-ups and neurodegeneration is still undeniable, and a big challenge for researchers has been the inability to clearly measure these toxic protein aggregations in living human subjects.

“No one doubts that amyloid plays a role in Alzheimer’s disease, but more and more tau findings are beginning to shift how people think about what is actually driving the disease,” explains lead author on the new research, Renaud La Joie. “Still, just looking at postmortem brain tissue, it has been hard to prove that tau tangles cause brain degeneration and not the other way around. One of our group’s key goals has been to develop non-invasive brain imaging tools that would let us see whether the location of tau buildup early in the disease predicts later brain degeneration.”

Positron emission tomography (PET) is one of the best tools researchers currently have at their disposal to image different protein accumulations in the brain. Until recently it was almost impossible to clearly identify tau aggregations in a living human brain, however, a recently developed imaging agent called flortaucipir has been nothing short of a game-changer.

Over the last few years researchers have increasingly found flortaucipir PET imaging to effectively measure tau levels in living patients. This breakthrough has subsequently led to studies examining tau levels in brains at the very earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease. For the first time researchers can now evaluate this chicken or the egg conundrum, and UC San Francisco scientists are suggesting tau levels effectively precede Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

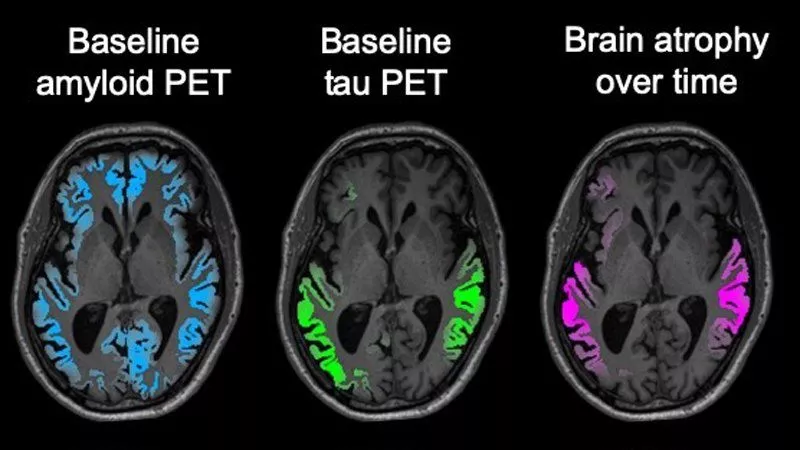

The new study recruited 32 subjects with early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Every subject received two bouts of PET imaging around 15 months apart, tracking both amyloid and tau levels in the brain. The primary goal was to evaluate whether amyloid or tau better predicted subsequent brain atrophy and disease progression.

“The match between the spread of tau and what happened to the brain in the following year was really striking,” says Gil Rabinovici, leader of the PET imaging program at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center. “Tau PET imaging predicted not only how much atrophy we would see, but also where it would happen. These predictions were much more powerful than anything we’ve been able to do with other imaging tools, and add to evidence that tau is a major driver of the disease.”

Unfortunately, this new discovery will not directly translate into wide clinical diagnostic applications. This kind of PET imaging is expensive and time-consuming, so it cannot easily be deployed by doctors as part of a routine health check-up. But, for researchers, this discovery should significantly help accelerate clinical trials investigating prospective new drug treatments.

“Tau PET could be an extremely valuable precision medicine tool for future clinical trials,” says Rabinovici. “The ability to sensitively track tau accumulation in living patients would for the first time let clinical researchers seek out treatments that can slow down or even prevent the specific pattern of brain atrophy predicted for each patient.”

The new research was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Source: UC San Francisco