A new, dissolving, textile-based stem cell implant has reduced pain and restored hip joint function to dogs with moderate osteoarthritis, in what researchers say could be a first step toward less invasive joint resurfacing in dogs as well as humans.

Instead of resurfacing the joint with an artificial material, this implant uses a new technique that allows the body to regenerate its own cartilage tissue through the use of stem cells.

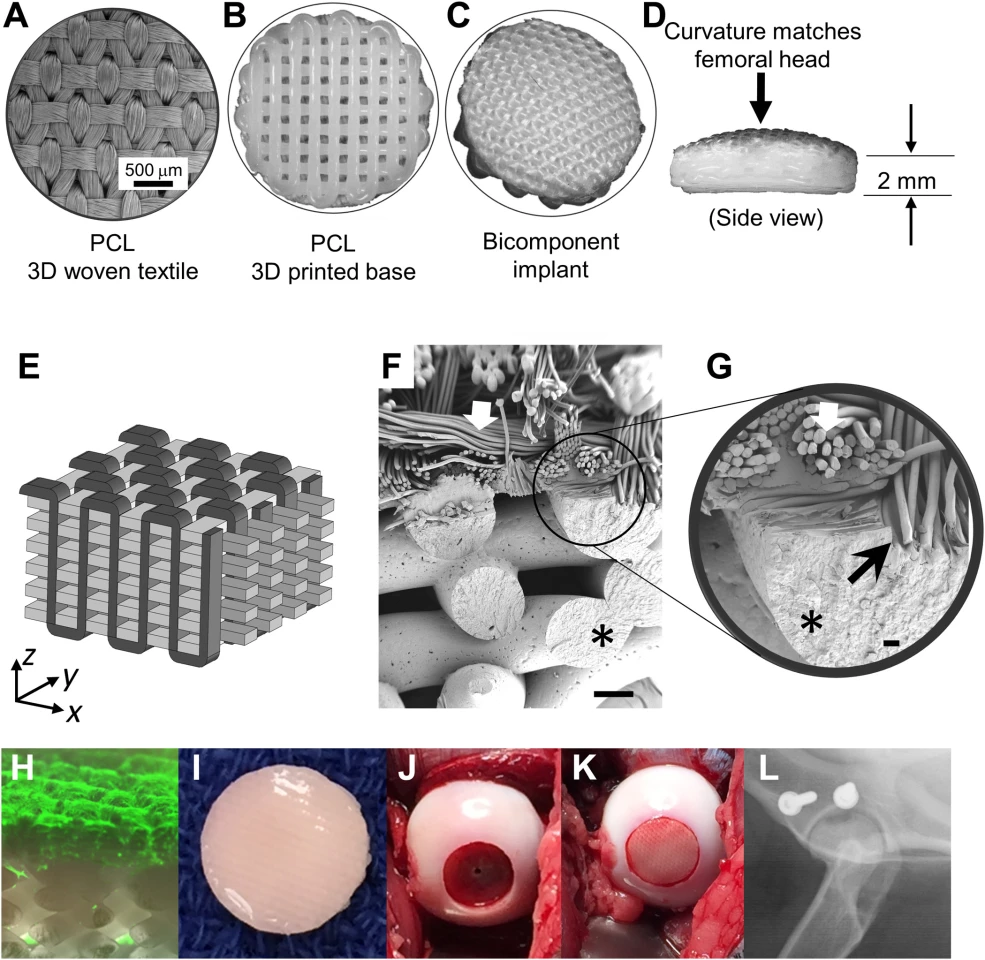

The implant is partially 3D printed, and partially made in advanced textiles. Before surgery, it's impregnated with the patient's own stem cells, then kept in an incubator, bathed in specific solutions and allowed to grow into cartilage over a period of around two months. Immediately after surgery, the implant acts like artificial cartilage, restoring function from day one.

But over time, it's designed to dissolve away, leaving nothing but the body's own new cartilage tissue that's grown to replace it.

The team, led by researchers from North Carolina State University, Washington University in St. Louis, and Cytex Therapeutics, trialed the technique on a group of 12 "skeletally mature hounds," which were given "massive osteochondrial lesions" in their hips and split into control and study groups.

Four months post-surgery, the team reports that where control group dogs saw no improvement, "the group that received the cartilage implant had returned to baseline levels for both function and pain." The researchers also "saw evidence that the implant had successfully integrated into the hip joints, effectively resurfacing them."

"What we saw is that with the implant these dogs were doing as well as or better than they would be after a total joint replacement," says Duncan Lascelles, professor of surgery and translational pain research and management at NC State and co-corresponding author of the research.

"We were thrilled that the implant was so effective at restoring the activity levels of the animals," adds Cytex co-founder Bradley Estes. "After all, this is why patients go see their physicians – they want to be able to play tennis, play with their kids, and, in general, re-engage in a pain-free active lifestyle that had been taken away by arthritis."

The team sees this treatment as an early intervention that "could be a major advance in postponing joint replacements for dogs and hopefully one day for humans," according to Lascelles. Joint replacements performed early in life often require multiple revisions as patients age, each replacement hip typically failing faster than the last.

This study serves as preliminary data only; further research including "longer time points and other preclinical work" is required before the technique could move to a phase 1 clinical trial in human patients.

The research was published in Science Advances.

Source: North Carolina State University