US researchers have developed an innovative smartphone-based kit that can test saliva samples for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses. Early studies have found the cheap system is as accurate as current lab-based testing and significantly faster.

Many people are most likely intimately familiar with the varieties of ways they can be tested for the virus that causes COVID-19. The two common options we currently have are PCR tests and rapid antigen tests.

Rapid antigen tests are quick and easy but can often miss positive cases. The test requires a certain amount of viral material to be captured by a nasal swab or saliva samples.

PCR, or polymerase chain reaction, technology is the most accurate way to test for SARS-CoV-2. It involves taking a swab sample from a subject and amplifying the viral genetic material in a lab.

In order to amplify the viral fragments a sample is subjected to a number of cycles that force the genetic material to replicate. These cycles involve rapid temperature changes spanning 50 to 95 °C (122 to 203 °F), repeated up to 30 times. And very particular equipment is needed to complete this process, meaning PCR testing requires access to specialized labs.

This new testing process is based on a different technology known as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), which is similar to PCR in that it identifies viral material through a process of amplifying any DNA present.

However, the novelty of LAMP technology is that it can amplify viral material without the complex temperature cycling required by PCR testing. The main problem with LAMP diagnostics has been over-sensitivity. It is so effective at enhancing viral replication that it often results in high volumes of false-positives.

One of the major innovations in this new research, explains one of the study’s authors, Douglas Heithoff, is solving this high-sensitivity LAMP problem – a problem that has, for decades, limited the broader deployment of LAMP testing technology.

“The key finding was solving the LAMP ‘primer-dimer’ problem – false positives due to high sensitivity – which scientists have struggled with for more than 20 years,” says Heithoff. “It took more than 500 attempts to solve it for COVID-19, after which flu viruses were detected on the very first try.”

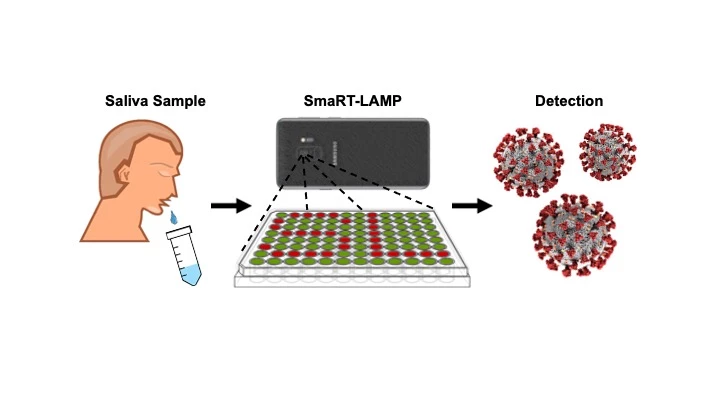

Alongside solving this false-positive problem the researchers designed a novel smartphone-based system that can be produced for less than US$100. The system has been dubbed smaRT-LAMP (smartphone-based real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification).

Using just a smartphone, LED lights and a hotplate, the researchers claim saliva samples can deliver accurate results in 25 minutes. The cost of each individual test has been estimated at around $7, significantly less than a lab-based PCR test.

The system can also be easily adapted to detect other viruses. In its current iteration, the researchers have demonstrated that simply changing the primers used to interact with a saliva sample can shift the kit from detecting SARS-CoV-2 to the influenza virus.

The researchers have already developed a smartphone app that directs smaRT-LAMP users through the testing process. Currently the focus is on introducing this technology to parts of the world struggling with access to PCR testing.

“Rapid and affordable point of care testing is critically important for underserved communities around the world, many of which are struggling with inadequate diagnostic testing access and limited laboratory infrastructure,” said Lynn Fitzgibbons, a researcher working on the project.

Michael Head, a global health expert from the University of Southhampton, calls the smaRT-LAMP system "interesting" and "exciting", but he does point out there are still limitations in how accessible smartphone-based systems are in remote and low-income parts of the world. His work in Ghana has found many rural communities do not have access to smartphone technology so this kind of system would need more development before it could be helpful to those kinds of communities.

“We in the Northern Hemisphere do rather have a history of taking ‘our machine that goes bing’ to our favored country of choice, and presenting it as a fait accompli for them to use,” said Head, who did not work on this new research. “So, requesting input from the target populations is vital, to ensure any product has the best possible chance of success. New mobile diagnostics are certainly exciting, but implementation in resource-poor settings will need consideration beyond for example the accuracy of the test itself.”

A new study demonstrating the accuracy of the system was published in the journal JAMA Network Open.

Source: UC Santa Barbara