For all they do for us, our hearts aren't very good at repairing themselves. So when a person suffers a heart attack, their blood pump is left with a large amount of scar tissue, which can impede the organ's flexibility and thereby its function. Inspired by the way young hearts heal themselves, researchers have now found a way to transmute scar tissue into healthy tissue in mice, thereby walking back some of the damage brought about by heart attacks.

In the United States alone, someone has a heart attack every 40 seconds, which means finding a way to prevent and minimize the damage from these cardiac events is a major priority for scientists. While plenty of research goes into preventing heart attacks, we're now seeing investigations into how to repair the heart after it suffers damage, particularly the scar tissue that forms after a heart attack. That's because left-behind scar tissue is more rigid than healthy heart tissue. Because it flexes less, it can restrict the heart's proper functioning and lead to future complications.

Earlier this year, researchers in Australia found a way to combat heart scarring in rats by boosting elastin, a substance that gives some body tissues their stretchy qualities. In that study, the heart scars shrank and became more flexible, restoring the heart to near its normal function.

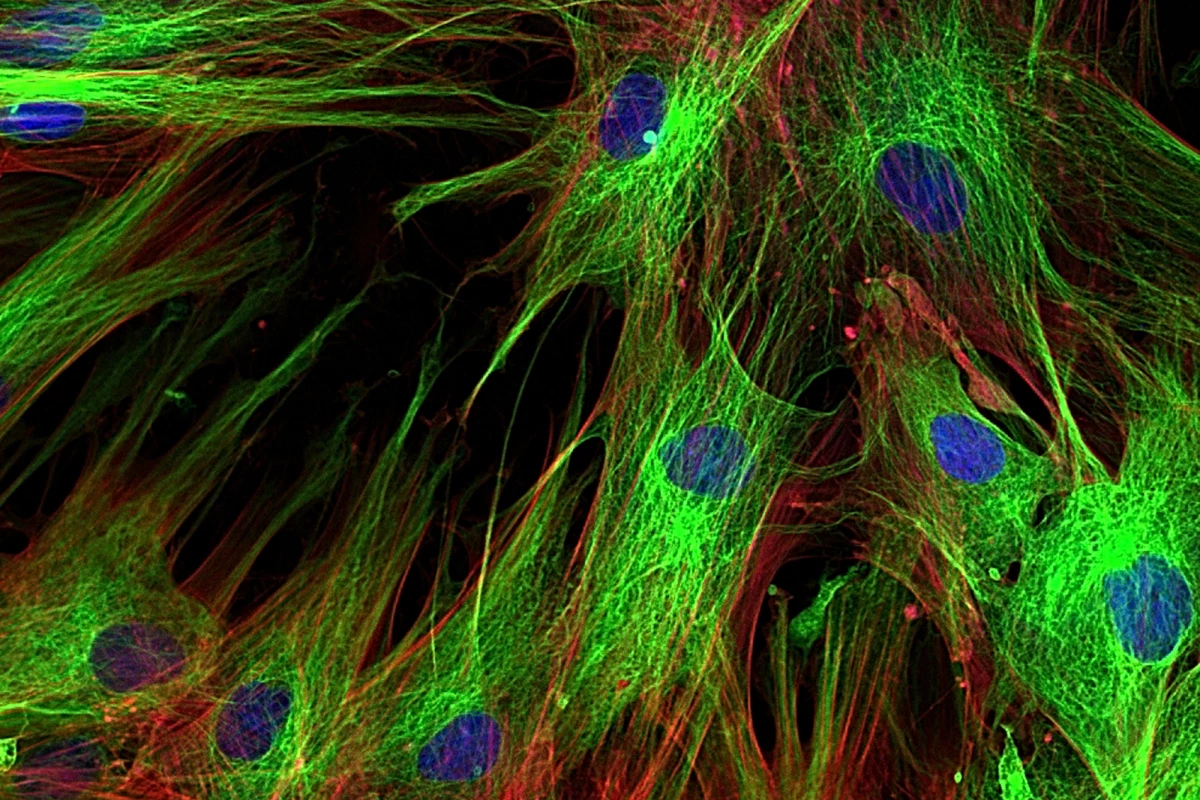

The new study was carried out by researchers at Duke University (DU), who looked to the function of fibroblasts, cells involved in forming both connective and scar tissue. Their plan was to use a process involving RNA called cellular reprogramming, that would convert fibroblasts back into healthy heart tissue following a heart attack. The technique has previously been studied not only with regard to heart repair efforts, but for restoring motor function in stroke victims, wound repair and more.

Working with mice however, they found that adult fibroblast cells were resistant to reprogramming, which was not the case with juvenile fibroblasts.

The difference, they found, involved a protein oxygen sensor known as Epas1, which kept the adult cells from following the reprogramming instructions. When Epas1 was inhibited in the adult cells, they underwent successful transformation.

Young again

"When we reversed the fibroblast aging process, essentially making the fibroblasts think they were young again, we converted more fibroblasts into cardiac muscle," said Conrad Hodgkinson, an associate professor of medicine and pathology at DU School of Medicine who oversaw the study.

With the Epas1 inhibited, the research team sent RNA packages into mice who'd had heart attacks. The RNA contained the reprogramming instructions to convert fibroblasts into healthy heart tissue and were wrapped in exosomes, sac-like structures found throughout the body.

"Exosomes are kind of like shopping bags," Hodgkinson said. "The cell sticks a lot of stuff into a big fat ball to send out and signal to other cells. They are a way cells can talk to each other."

The technique proved successful.

"We were able to recover almost all of the cardiac function that was lost after a heart attack by reversing the aging of the fibroblasts in the heart," said Hodgkinson.

Because the research not only employed cellular reprogramming, but a way to reverse the effects of aging on some cells, the researchers say the findings could have an impact in other areas of medicine, including regenerating neurons in the brain, and reversing skin scarring in certain dermatological conditions.

The study has been published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Source: American Society For Biochemistry And Molecular Biology via EurekAlert