Australian researchers have achieved two firsts that will assist in the global battle against heart disease: they created a tiny beating heart with its own vascular system and then uncovered how the vascular system affects inflammation-driven heart damage.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are one of the leading causes of death globally. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CVDs claim an estimated 17.9 million lives yearly. Death rates due to CVDs are expected to rise, given our aging population and the impact of lifestyle-related risk factors.

CVDs include any condition that affects the heart or circulation, such as heart attack and coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, stroke, and vascular dementia. Given the prevalence of CVDs, it’s important that research continues to uncover new ways of preventing, diagnosing and treating this group of diseases.

Australian researchers have contributed to the acceleration of research in the area of heart disease with their creation of a tiny heart organoid.

Organoids are tiny structures that mimic human organs. They’re grown in a lab, using human pluripotent stem cells, which can be generated using ‘reprogrammed’ skin or blood cells.

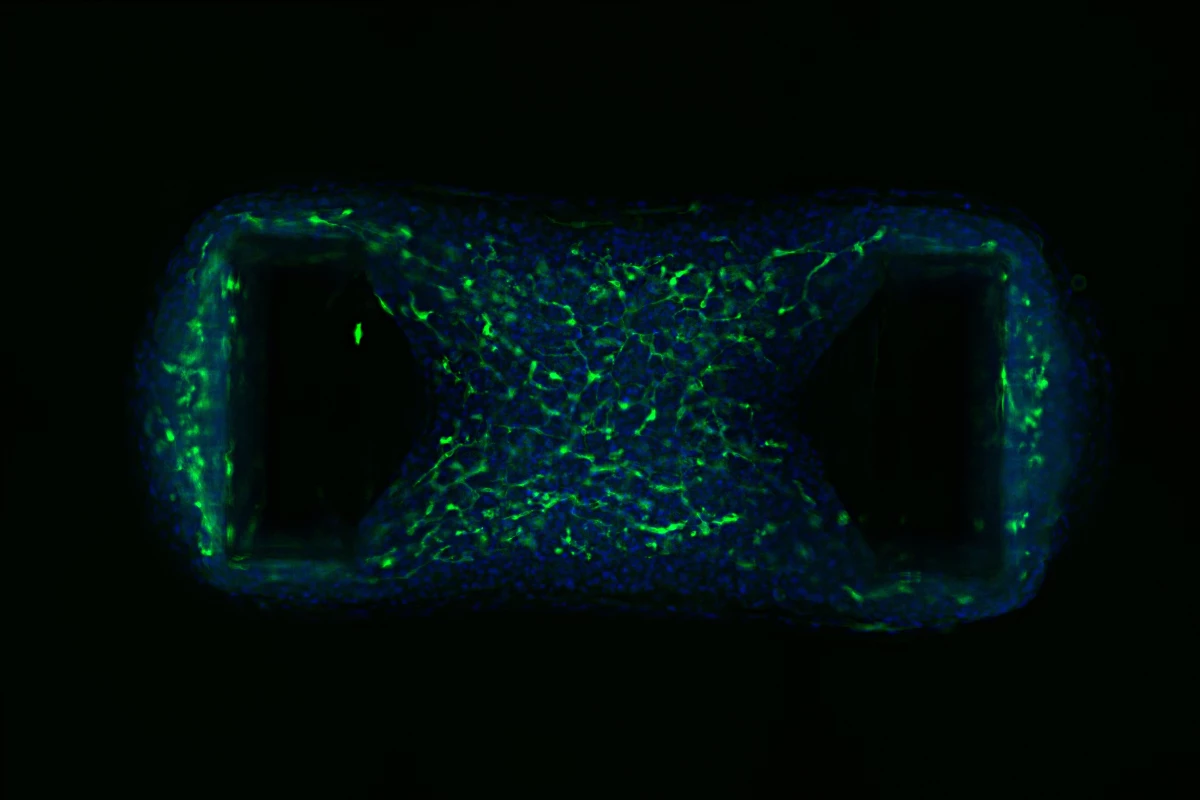

“Each organoid is only about the size of a chia seed, measuring just 1.5 millimeters [0.06 in] across, but inside are 50,000 cells representing the different cell types that make up the heart,” said James Hudson, corresponding author of the study.

Here, researchers created a tiny beating organoid, which is nothing new. But, for the first time, they were able to successfully incorporate vascular cells, the cells that line blood vessels, bringing the model heart even closer to replicating the real thing.

“Incorporating the vascular cells for the first time in our mini heart muscles is very significant because we found they had a key role in the biology of the tissues,” Hudson said. “Vascular cells made the organoids function better and beat strongly. This has really opened up our ability to better understand the heart and accurately model disease.”

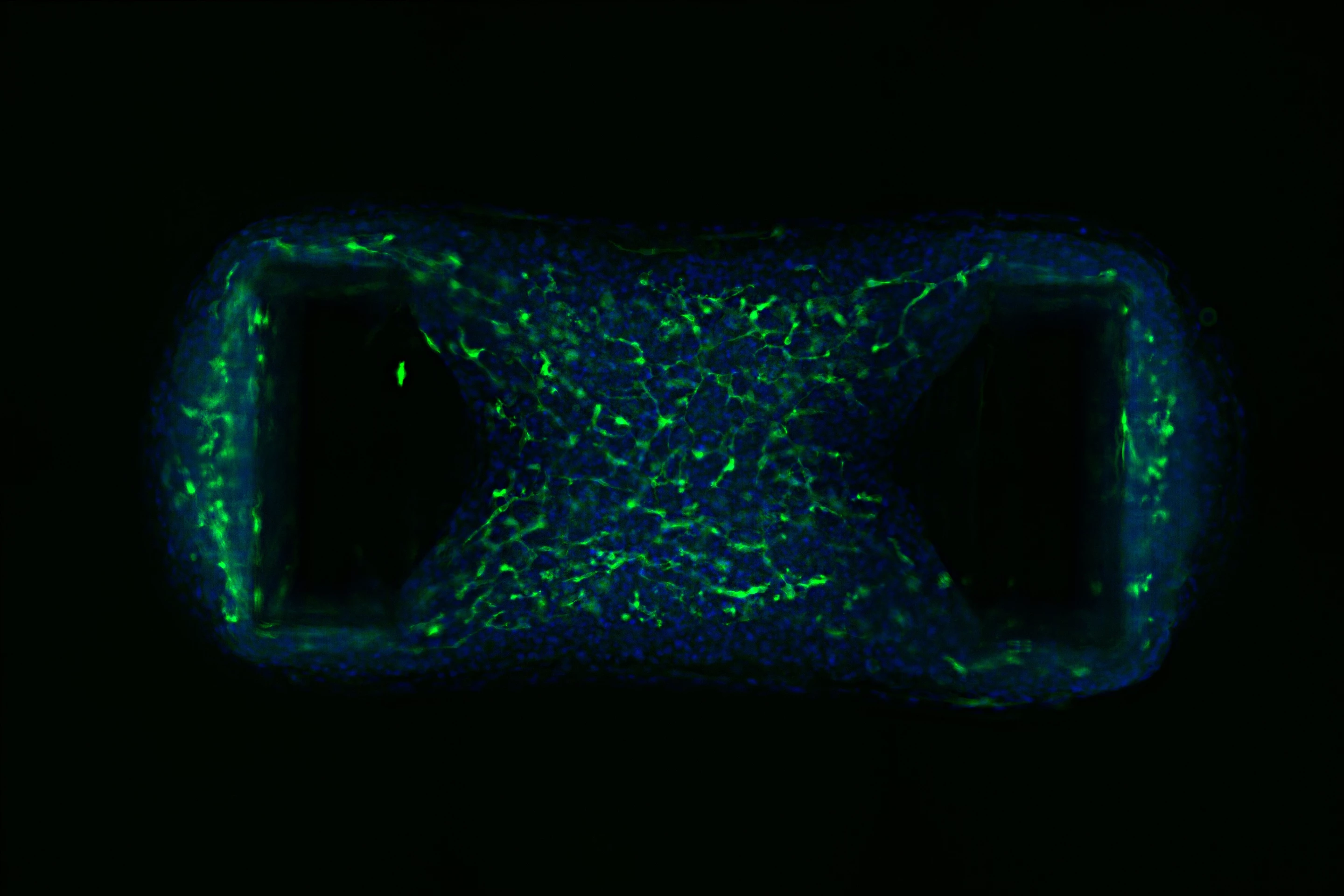

The added bonus of vascular cells meant that the researchers could investigate how they affect inflammation, which can cause the heart to stiffen. In another first, the researchers uncovered the key role the vascular system plays in inflammation-driven heart muscle injury.

“When we stimulated inflammation in our mini heart muscles, we found the vascular cells played a central role,” said Hudson. “We only saw the stiffening in the tissues that had the vascular cells. The cells sensed what was happening and changed their behavior, and we identified that the cells release a factor called endothelin that mediates the stiffening.”

The researchers say that this discovery, and the use of their novel heart organoid, could lead to new treatments for heart disease.

“That’s where our new system of producing vascularized cardiac organoids will really give us an advantage because we’ll be able to progress the search for new treatments much more quickly,” Hudson said.

Publication of the study will help researchers worldwide create their own vascularized organoid, boosting the global effort to tackle heart disease, the researchers say. Moreover, they say their discovery could be used to create kidney and brain organoids, accelerating research into the diseases that affect those organs.

The study was published in the journal Cell Reports, and the below video from the QIMR Berghofer shows the novel human heart organoid in action. James Hudson, one of its creators and authors of the current study, explains how the organoid was created and how it might be used.

Source: QIMR Berghofer