Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a way to 'supercharge' vaccines to the extent that just a single dose can provide strong protection from HIV.

Vaccines typically comprise two key components: immunogens that trigger an immune response in the body, and adjuvants which boost your immune system's response to the immunogens. The MIT team, which collaborated with the medicine-focused Scripps Research Institute, focused on the latter, and actually combined two adjuvants to elicit a significantly better immune response than a vaccine with just either of them.

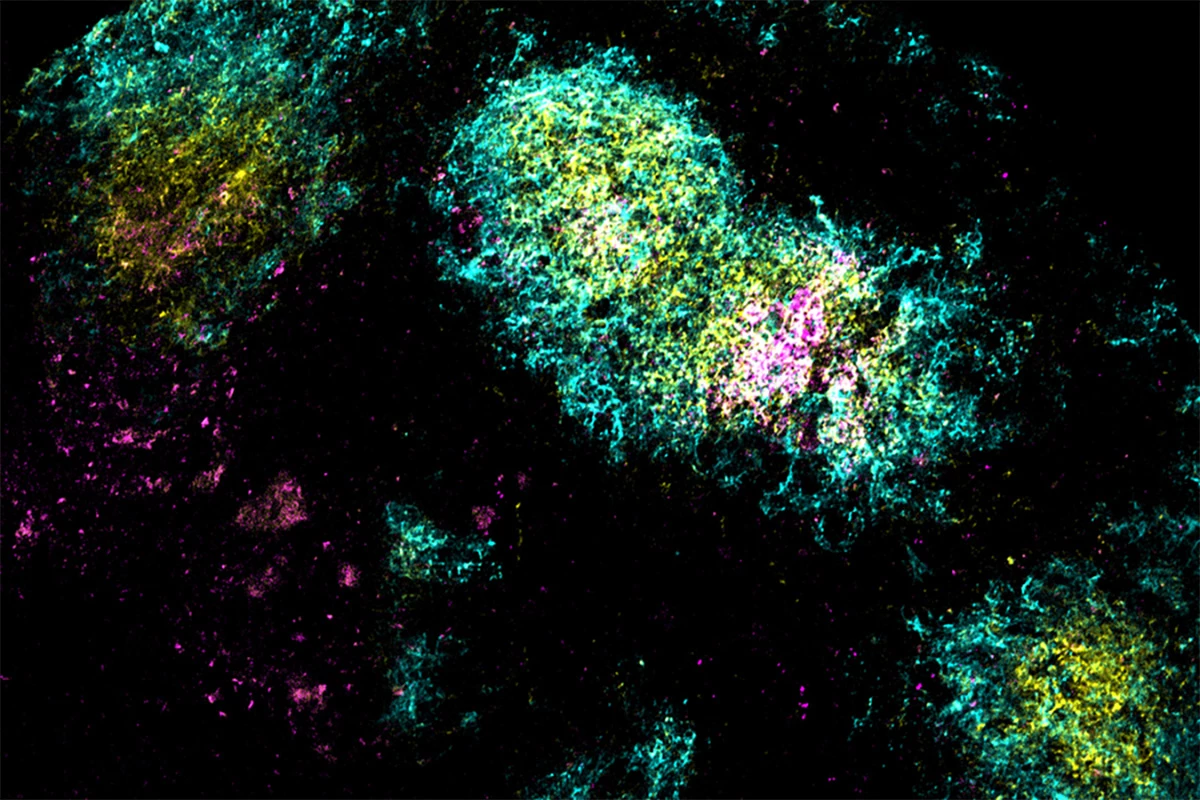

In the team's study, whose results appeared in a paper in Science Translational Medicine this week, mice that received the dual-adjuvant vaccine exhibited a much wider range of antibodies against an HIV antigen, compared to those who received a vaccine with only one of the adjuvants.

The adjuvants in question are the commonly used aluminum hydroxide or alum, and a nanoparticle called SMNP developed by researcher and immunology professor Darrell Irvine. SMNP contains saponin, an adjuvant derived from the Chilean soapbark tree, and a synthetic adjuvant called Monophosphoryl Lipid A (MPLA).

In this work, the researchers found that the dual-adjuvant vaccine boosted what's called the B cell response by two to three times more than single-adjuvant formulations. These B cells produce antibodies that can recognize a pathogen the body has previously been exposed to, and that gives you a better chance of fighting off dangerous viruses.

Indeed, the new approach caused the dual-adjuvant vaccine to accumulate in the mice's lymph nodes and stay there for a month, during which time their immune systems effectively built up plenty of antibodies against the HIV protein.

"What’s potentially powerful about this approach is that you can achieve long-term exposures based on a combination of adjuvants that are already reasonably well-understood, so it doesn’t require a different technology," chemical engineering professor J. Christopher Love remarked. "It’s just combining features of these adjuvants to enable low-dose or potentially even single-dose treatments.”

According to the researchers, this approach could come in handy for formulating protein-based vaccines to protect against many more challenging viruses, including influenza and SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID-19).

Interestingly, this breakthrough comes just as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Lenacapavir, a twice-yearly injection that's described as a 'near-perfect shield against HIV infection.' Rolling it out might prove challenging, as major global health programs that would procure and distribute the drug in low-income countries, have been slashed or undermined.

For context, HIV has already claimed more than 42 million lives worldwide, and nearly as many people were estimated to be living with the condition by the end of 2023. Of those people, 65% are in Africa. And in 2023, it was estimated that 1.3 million were infected with HIV globally.

Measures to prevent infection, such as strong vaccines, will prove vital to fighting this disease in the years to come.

Source: MIT News