Scientists have performed the first successful transplant of an organ that had been cryogenically frozen and rewarmed, thanks to a new preservation chemical. Rats that were given transplants of kidneys preserved through this technique regained regular organ function within weeks, paving the way for more successful organ transplants in humans.

Organ transplants can save lives, but unfortunately there’s a very short window where they remain viable between donor and recipient. That means that scores of organs go to waste, even while waitlists for them continue to grow. Freezing organs can prolong their storage times, but ice crystals that form between cells can damage the tissue, rendering many unusable.

An alternative technique called vitrification sidesteps this problem by snap-freezing organs to extremely low temperatures using cryoprotective chemicals, which invokes a glass-like state that doesn’t form ice crystals. Unfortunately, the tricky part there is defrosting organs without damaging them – current rewarming methods start from the surface, resulting in uneven heating. As areas of the tissue warm up at different rates, they expand at different rates and create cracks or tears.

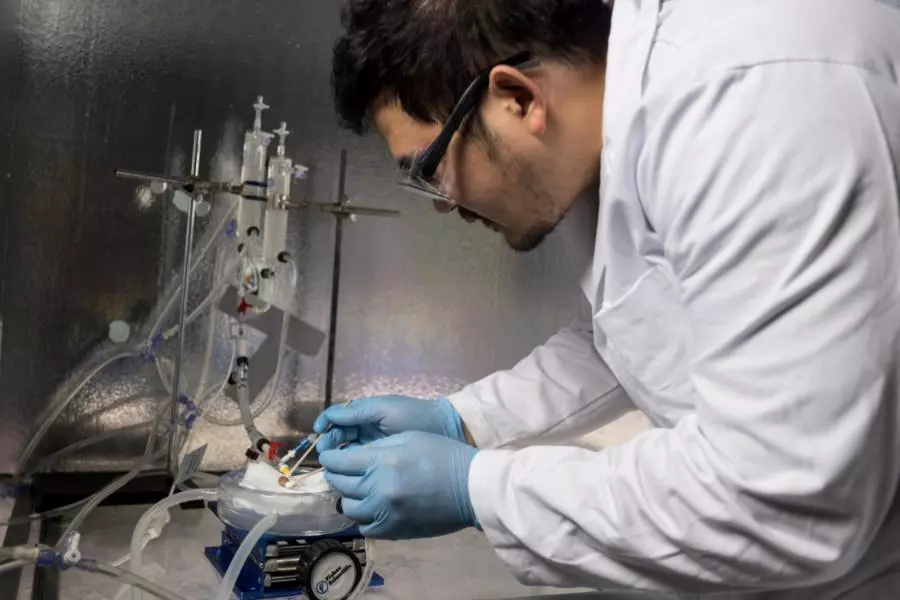

But in recent years, researchers at the University of Minnesota have developed a new rewarming technique that heats up a frozen organ quickly and evenly, from the inside out. The trick is to add iron oxide nanoparticles to the cryoprotectant chemical. When alternating magnetic fields are applied to the organ, these nanoparticles – dispersed throughout the organ’s blood vessels – all act like tiny heaters, warming up the organ evenly.

In the new study, the scientists demonstrated that the technique does work in live animal tests. The team cryogenically stored rat kidneys for 100 days, rewarmed them, cleared out the fluids and nanoparticles used to preserve them, and then transplanted them into rats. All five recipients not only survived the procedure but regained full kidney function within 30 days.

“This is the first time anyone has published a robust protocol for long-term storage, rewarming, and successful transplantation of a functional preserved organ in an animal,” said John Bischof, co-senior author of the study. “All of our research over more than a decade and that of our colleagues in the field has shown that this process should work, then that it could work, but now we’ve shown that it actually does work.”

The team says this important milestone could eventually lead to long-term organ banking, which would reduce wasted donations and wait times, improve donor/recipient matching and ultimately save more lives. The next steps will be to test the technique on pig kidneys.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: University of Minnesota