Platelets are best known for stopping bleeding by clumping together to produce blood clots. But researchers have discovered they have an unexpected ability: they produce a biochemical that has been found to rejuvenate the brains of aged mice, similar to the way physical exercise does. The discovery may lead to drugs that improve the cognitive function of older people who can't exercise because of mobility issues.

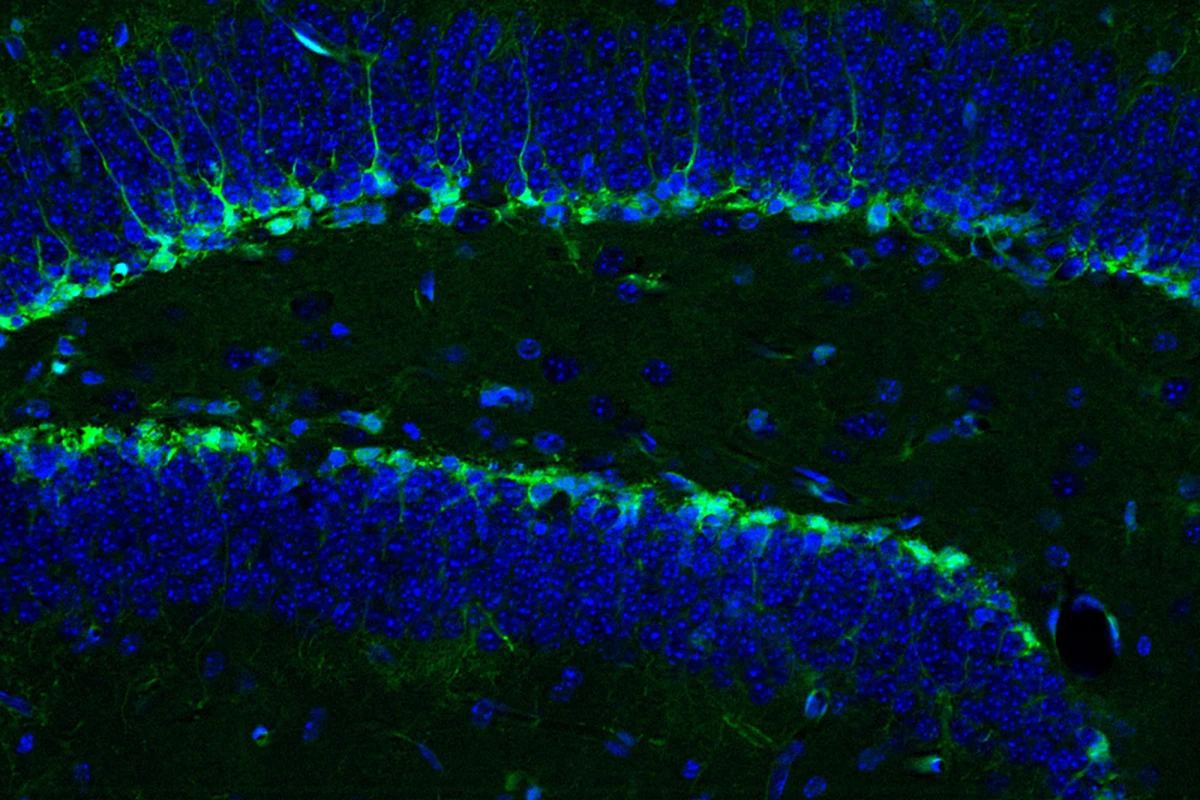

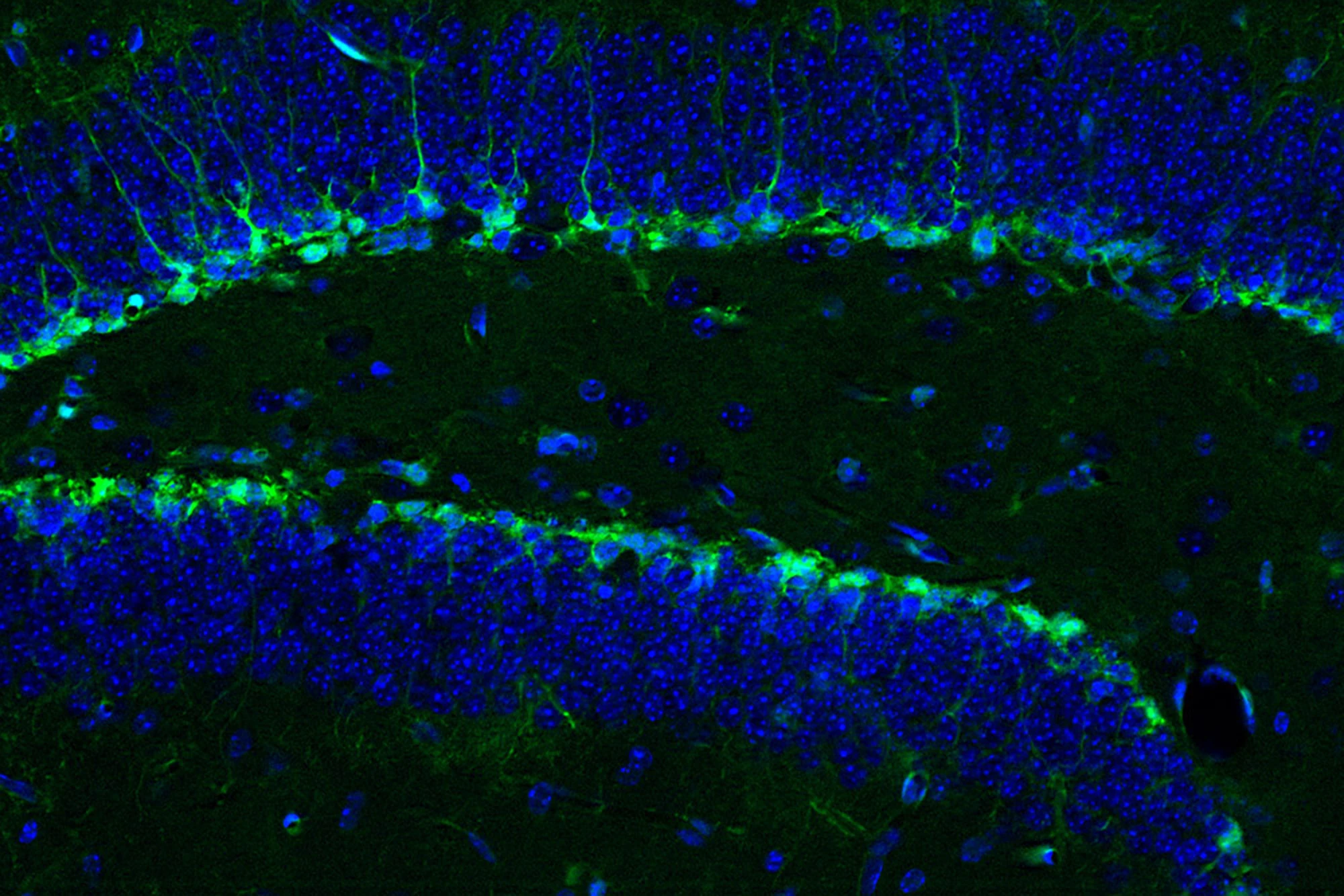

Much research has proven that regular physical exercise can counter age-related cognitive decline and the decline seen in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. While the molecular mechanisms underpinning how exercise benefits the brain remain poorly understood, animal studies have found that exercise promotes the growth of new cells in the hippocampus, a part of the brain involved in learning and memory, by causing the release of exerkines.

This is where platelets come in. Researchers from the University of Queensland recently discovered that the colorless cell fragments that circulate in our bloodstream and are best known for clumping together to prevent and stop bleeding in damaged vessels, had another unexpected function: producing biochemicals called exerkines. In a new study, the researchers investigated how platelets, and the exerkines they produce, affect the brains of aged mice.

“We know exercise increases production of new neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain important for learning and memory, but the mechanism hasn’t been clear,” said Odette Leiter, the study’s lead author. “Our previous research has shown platelets are involved, but this study shows platelets are actually required for this effect in aged mice.”

Their previous research showed that exercise-affected platelets released a particular exerkine called chemokine platelet factor 4 (PF4), so that’s what they focused on in the current study. Knowing that when PF4 was delivered directly to the brains of young mice it enhanced the growth of new cells (neurogenesis) in the hippocampus, they examined how the aged brain would respond and whether PF4 would kick-start neurogenesis and mitigate cognitive decline.

They administered PF4 to aged mice and tested their hippocampus-associated learning and memory. The PF4-treated mice performed better than those who received a saline-only injection, suggesting that PF4 treatment augmented the benefits of exercise by rejuvenating hippocampal neurogenesis and restoring cognitive function.

“We discovered that the exerkine CXCL4/Platelet factor 4 or PF4, which is released from platelets after exercise, results in regenerative and cognitive improvements when injected into aged mice,” Leiter said.

The researchers say their discovery could help the development of drug interventions, especially for people who can’t exercise due to issues with mobility.

“For a lot of people with health conditions, mobility issues or of advanced age, exercise isn’t possible, so pharmacological intervention is an important area of research,” said Tara Walker, corresponding author of the study. “We can now target platelets to promote neurogenesis, enhance cognition and counteract age-related cognitive decline.”

They stress, however, that the treatment is not meant to replace exercise.

“It’s important to note this is not a replacement for exercise,” Walker said. “But it could help the very elderly or someone who has had a brain injury or stroke to improve cognition.”

The researchers next intend to research how Alzheimer’s diseased mice respond to PF4 before moving to human trials.

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: University of Queensland