New research presented at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society has demonstrated how tiny roundworms can be used to detect lung cancer. A “worm-on-a-chip” device has been developed that is currently 70 percent effective at detecting cancer cells.

Humans have long exploited the olfactory skills of other organisms. Most familiar is our use of dogs to detect everything from drugs and explosives to cancer and malaria. But more recently researchers have turned to other other organisms, such as mice, honeybees and locusts, as they are often much easier to train and cheaper to manage.

Earlier this month a team of researchers in France demonstrated a method for training ants to detect cancer cells. The preliminary findings revealed ants could be as accurate in homing in on cancer cells as dogs.

This new research, yet to be peer-reviewed and published, goes even smaller than ants, looking at tiny roundworms called Caenorhabditis elegans. Prior lab studies with urine samples have found these roundworms seem to preferentially move toward samples from patients with cancer so the new research looked to turn this behavioral characteristic into a simple diagnostic test.

“Lung cancer cells produce a different set of odor molecules than normal cells,” explained Shin Sik Choi, principal investigator on the research from Myongji University in Korea. “It’s well known that the soil-dwelling nematode, C. elegans, is attracted or repelled by certain odors, so we came up with an idea that the roundworm could be used to detect lung cancer.”

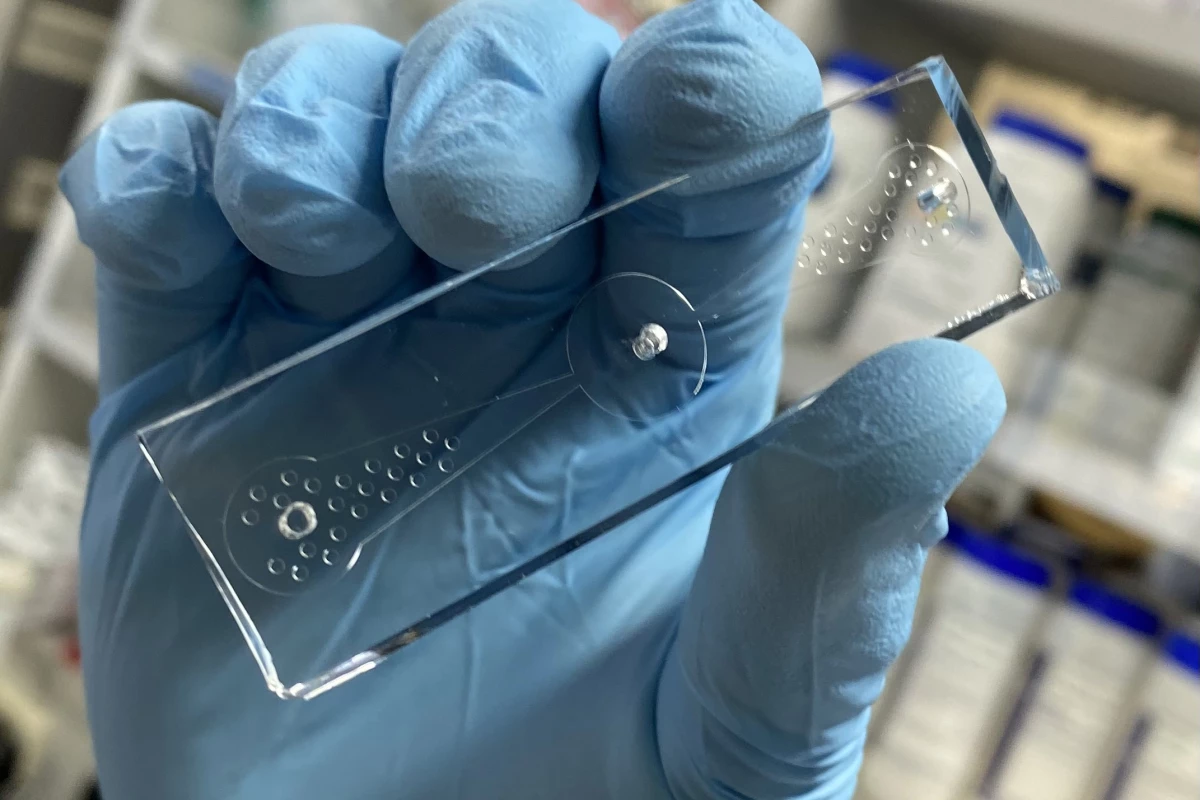

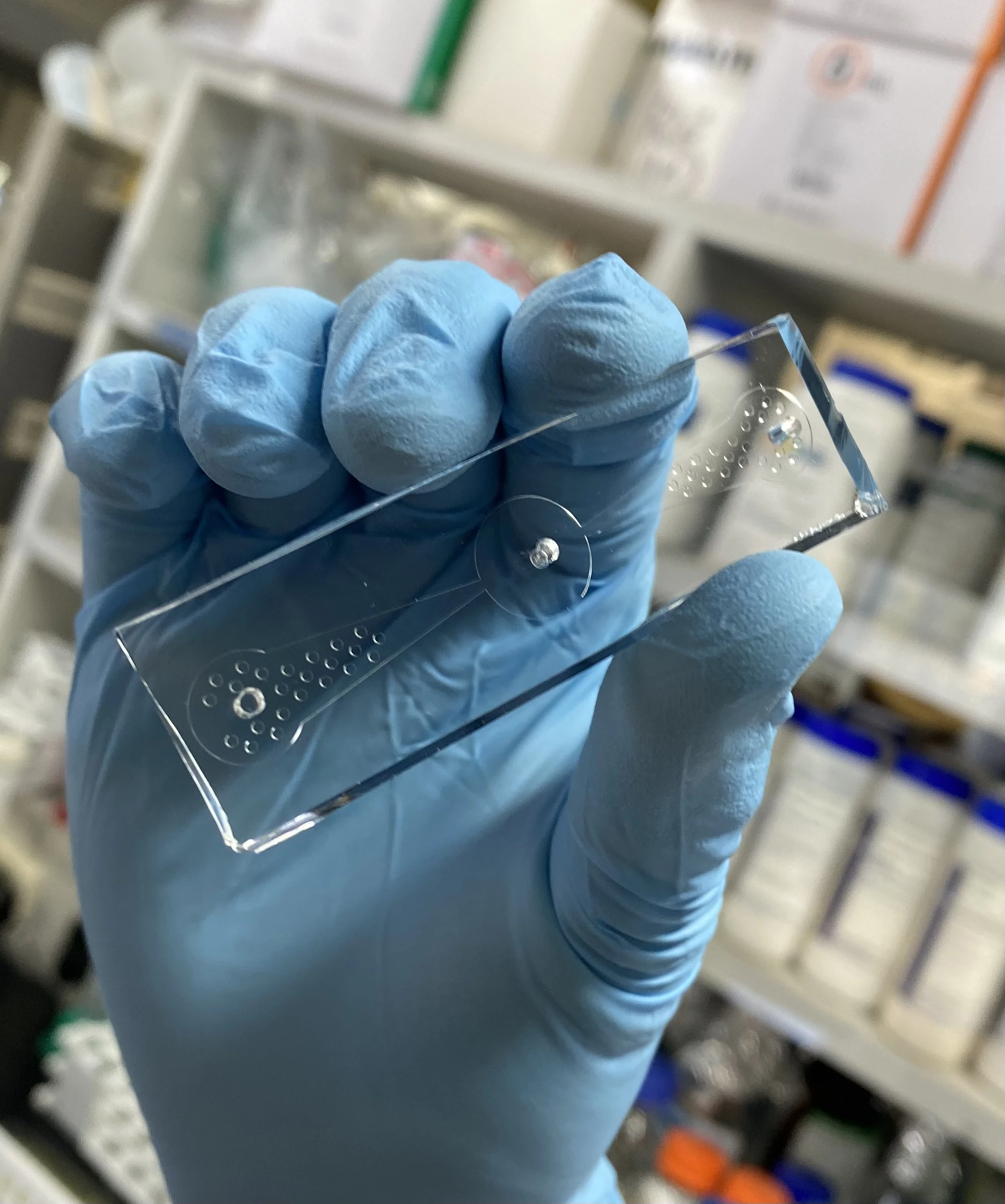

The researchers created a simple plastic chip with wells at either end connecting to a channel in the middle holding a small number of the roundworms. A culture from lung cancer cells was placed in a well at one end and healthy lung cells were placed in the well at the other end.

After one hour the researchers said a significantly higher volume of worms moved to the lung cancer cells than the healthy cells. Early results showed this device could be used to detect cancer cells with 70 percent accuracy.

To confirm the organisms were attracted to certain odor particles the researchers conducted the same test using roundworms with gene mutations designed to disrupt their olfactory senses. The roundworms with mutated odor genes did not display the same preferential behavior targeting the cancer cells.

Another experiment focused on what specific volatile organic compound was attracting the roundworms. The researchers discovered the organisms seemed to be attracted to a molecule called 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, present in lung cancer tissue.

“We don’t know why C. elegans are attracted to lung cancer tissues or 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, but we guess that the odors are similar to the scents from their favorite foods,” said So Jang, another researcher working on the project.

The work is still deeply in preliminary stages and the researchers are initially looking at ways to optimize the accuracy of the current test. Nevertheless, looking ahead the “worm-on-a-chip” device could hypothetically be used to target a range of cancers in a cheap and non-invasive way.

“We will collaborate with medical doctors to find out whether our methods can detect lung cancer in patients at an early stage,” Choi added.

Source: American Chemical Society