A "bi-sensory" treatment combining precisely timed sound and touch has shown impressive results in reducing people's experience of tinnitus, a common and debilitating form of hearing damage that presents as an incessant ringing sound in the ears.

That ringing sound can become incredibly penetrating and stressful, particularly in a silent room. It's not a real sound, it's believed to be generated in a brain region called the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN). The DCN is one of the first processing stops for audio signals in the brain, but it also processes touch sensations from the head, the ear and the jaw.

Researchers believe that tinnitus develops when the neural circuitry of the DCN is altered in response to cochlear damage from exposure to loud noise, causing the auditory system to perceive sounds that aren't there.

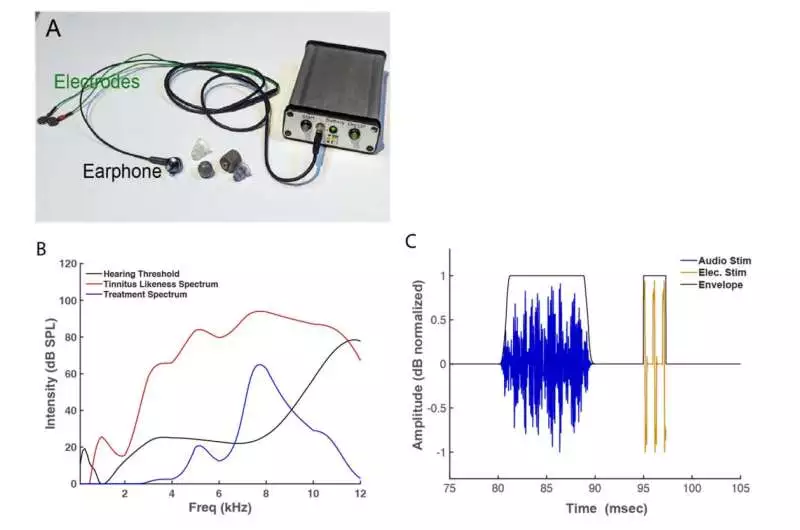

A University of Michigan team looked at animal studies, in which it was found that bi-sensory stimulation of the DCN via sound and touch signals could induce neuroplasticity, either strengthening or weakening the circuits associated with tinnitus, depending on the precise timing between the stimuli.

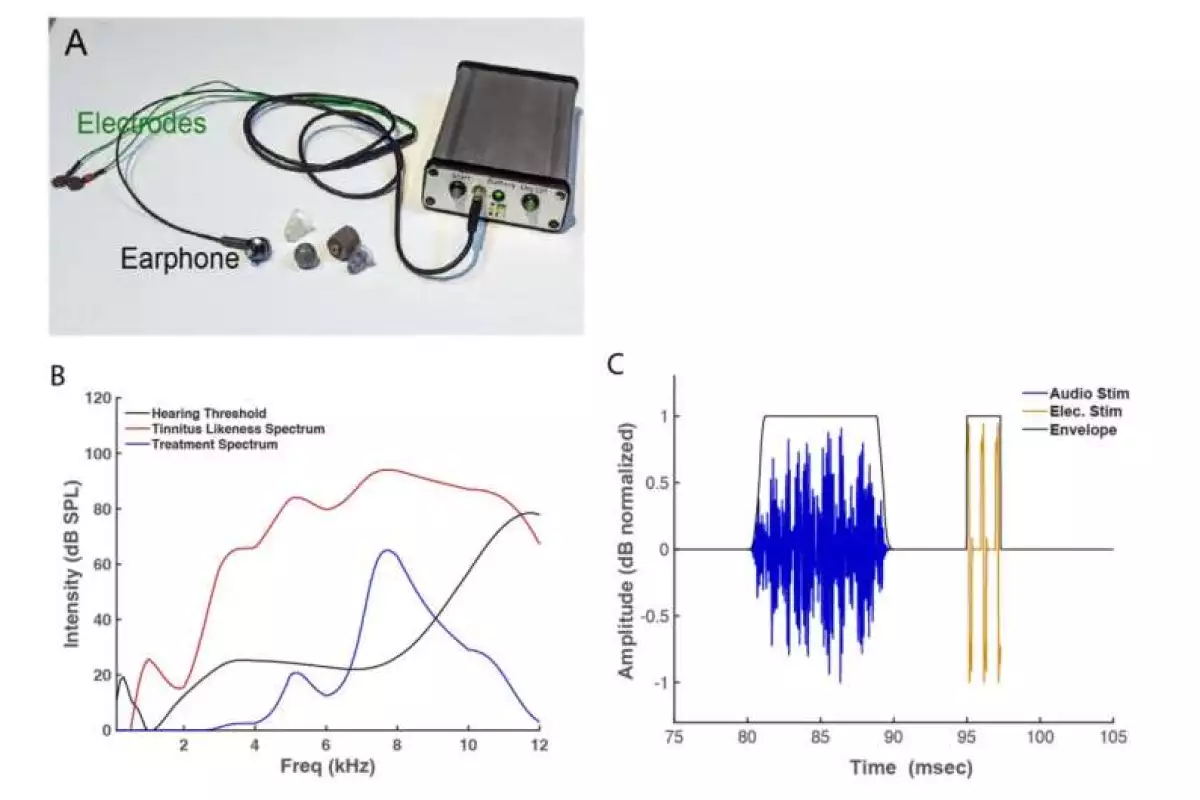

The researchers designed a human trial, in which 59 males and 40 females with tinnitus that could be modulated with jaw, head or neck motions – representing the majority of tinnitus patients – were trained in the use of a portable, take-home device running custom software.

Participants spent 30 minutes per day hooked up to this machine, with an electrode placed on the skin near the neck or face, to create tiny electrical pulses, just below the level participants were able to feel. These pulses were presented alongside short, low-volume pulses of audio designed to replicate the sound of the patient's tinnitus, with timing designed to shrink and weaken the tinnitus circuits in the DCN over time.

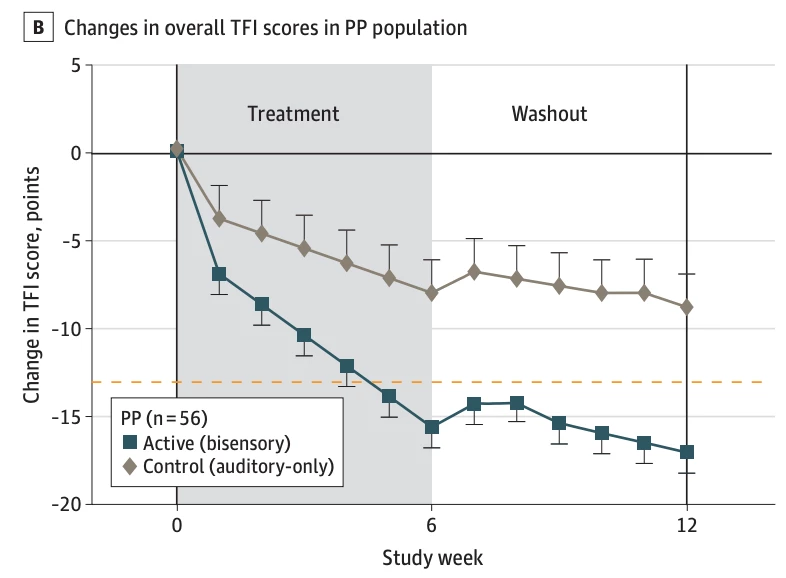

Roughly half the cohort received a control treatment for the first six weeks, without the electrical pulses. At six weeks in, both groups were given a six-week "washout" period in which they didn't have to do anything, and then the groups were switched for a second six-week treatment period. Anyone whose experience of tinnitus became worse during the program was taken out of the experiment. Patients reported they couldn't tell the difference between the active and control treatments.

In both six-week treatment phases of the experiment, the active group, on average, showed a clinically-significant improvement in their Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) scores, and the control group did not. A clinically significant improvement is defined as a 13-point drop in a patient's TFI score, and some 65% of active group patients who followed the test protocol achieved such a drop, while only 25% of control group patients experienced the same.

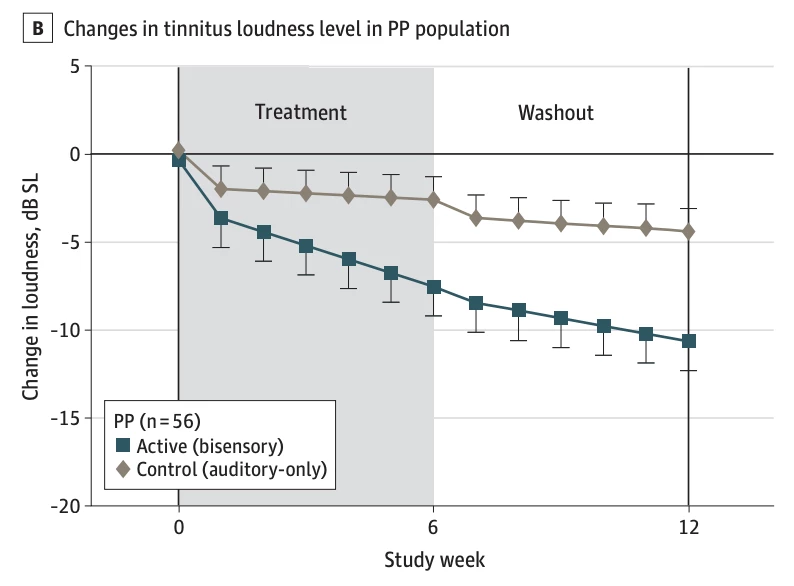

Active group patients who followed the test protocol experienced an average reduction of about 7.5 decibel sensation level in their tinnitus at the six-week mark. Unexpectedly, the first active group's symptoms continued to improve throughout the washout period without treatment, and after 12 weeks, their average reduction in symptoms was more than 10 decibel sensation level. The study didn't measure any similar long-term improvements in the second-phase active group.

The research team says these positive results indicate the treatment is likely to have a lasting positive impact, and could result in personalized bi-sensory tinnitus treatments for sufferers.

The research paper is open access in the journal JAMA Network Open.

Source: University of Michigan