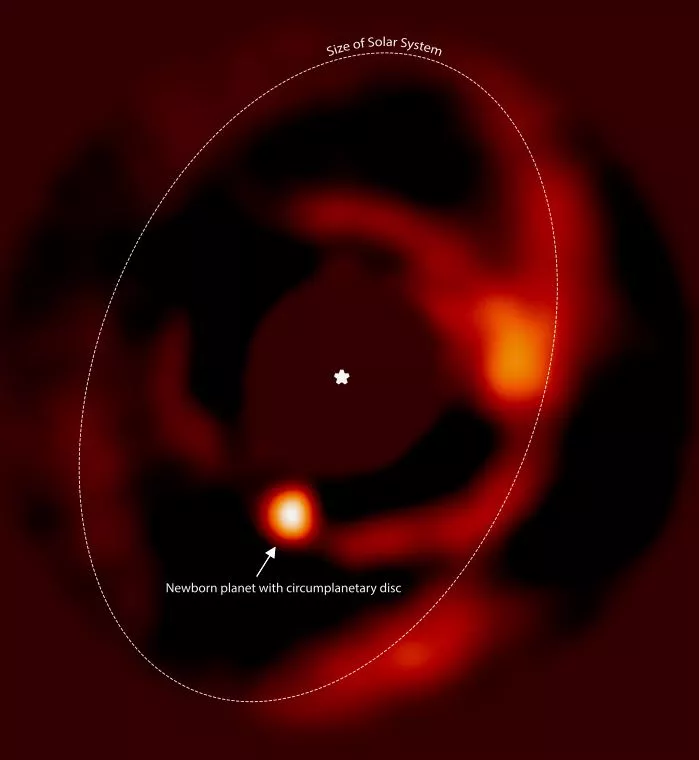

An international team of physicists has finally found proof of circumplanetary disks, adding substantial weight to current theoretical models of planet formation. These disks of gas surrounded by dust have eluded detection, until now.

The international study, led by the Monash School of Physics and Astronomy in Melbourne, Australia, looked at the very early stages of planet formation – typically only a few million years in – using the power of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) facility in Chile.

The VLT consists of four optical telescopes – each huge in their own right – which in this instance, were used together, making it functionally, the largest optical telescope on the planet. The research team, led by Dr Valentin Christiaens from Monash University, used the VLT to gather infrared images of different wavelengths of a newborn giant planet.

"We found the first evidence for a disc of gas and dust around it – known as a circumplanetary disk," says Dr Christiaens. "We think the large moons of Jupiter and other gas giants were born in such a disk, so our work helps to explain how planets in our Solar System formed."

Scientists have long searched for circumplanetary disks via numerous techniques and at different wavelengths, but to no avail. The key to this discovery lays in an algorithm developed by the team to extract faint signals from complex datasets. Since newborn planets were overwhelmed by the glare from the star they orbited, the star's glare needed to be removed from the images. Once this was done, the circumplanetary disk revealed itself.

"Despite an intensive search, circumplanetary disks have until now eluded detection," says Christiaens said. "This first piece of evidence suggests theoretical models of giant planet formation are not far off."

The discovery brings us closer to a more complete understanding of how our own Solar System – and we ourselves – came about.

The research has been published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters .

Source: Monash University