Madman daredevil Evel Knievel never managed to complete his most famous stunt: the rocket bike jump across Snake River canyon in 1974. But 42 years after millions watched Knievel's Skycycle X-2 fall a mile into the canyon after a parachute failure, somebody crazy enough to try to finish what Evel started has finally stepped forward. Stuntman Eddie Braun is going to attempt the jump in September, in a replica rocket bike called the Evel Spirit, which has been lovingly built by Scott Truax, the son of famed rocket engineer Bob Truax who built the original Skycycle X-2.

It's funny who we choose as childhood heroes. By most accounts, Evel Knievel was a violent, alcoholic, womanizing egomaniac driven to crazed paranoia by pain meds, booze and massive stardom. A con man and a thief.

But when I was learning to ride a bicycle as a young kid in the early 80s, he was everything. What kid of that era never put three bricks and a plank down and jumped a pushbike over their infant brother in his bassinet? Who didn't have an Evel Knievel action figure, the one that did wheelies and backflips?

Knievel is regarded by many as the father of extreme sports, the original motorcycle-jumping daredevil, the inspiration for a tidal wave of freestyle motocross jumpers that followed in the 1990s.

But the guys in the business today are landing double front flips and jumping nearly 350 feet in the air, and they're doing it in relative safety, using tailor-made motocross bikes, foam pits, inflatable crash barriers and meticulous preparation.

Knievel's situation couldn't have been more different. He was jumping streetbikes for starters, 500-pound mile-munching Harleys and Triumphs that could hurtle through the air just fine, but weren't fond of landing. His preparations were laughable, too; a friend would stand by the jump and eyeball it as he approached on a practice run, telling him if he looked like he was going quick enough to make it.

The very fact that he crashed and hurt himself almost as often as he landed a jump was a big part of what made Evel Knievel the unmissable spectacle he was. People tuned in to Wide World of Sports in their millions to see a man either defy gravity or succumb to it in a very visceral way. Knievel knew it; he used to say "nobody wants to see me die, but they don't wanna miss it if I do."

He wasn't afraid of pain or failure, learning early in his career that a bad crash tended to be better for business than a successful landing. And his failures were majestic – people remember them above everything else.

The bone-crunching ragdoll landing at Caesar's Palace. The back-and-pelvis shattering crash at Wembley Stadium, where his friends lifted his smashed motorcycle off his broken body and hauled him to his feet so he could walk out the way he walked in. And of course, the Snake River canyon jump.

The Snake River Canyon Jump

This was lunacy from its very conception. Strapping a man onto a rocket-powered motorcycle and launching him over a 1600-foot-wide gap looked like a fine way to turn a perfectly good human being into bolognese sauce.

But Knievel did have the best in the business at his disposal. Bob Truax was the biggest name in private rocketry in the late 60s, and he was focused on sending men and cargo into space without the billowing expenses and red tape of government involvement. A puny canyon jump should be a walk in the park.

The first Skycycle design, the X-1, was designed in conjunction with Doug Malewicki, inventor of Robosaurus, the car eating dinosaur. The plan was for the X-1 to look as much like a motorcycle as possible, but with angled wings and a pair of rockets hanging off the side. As such, it performed horribly, and went straight in the drink in its first test.

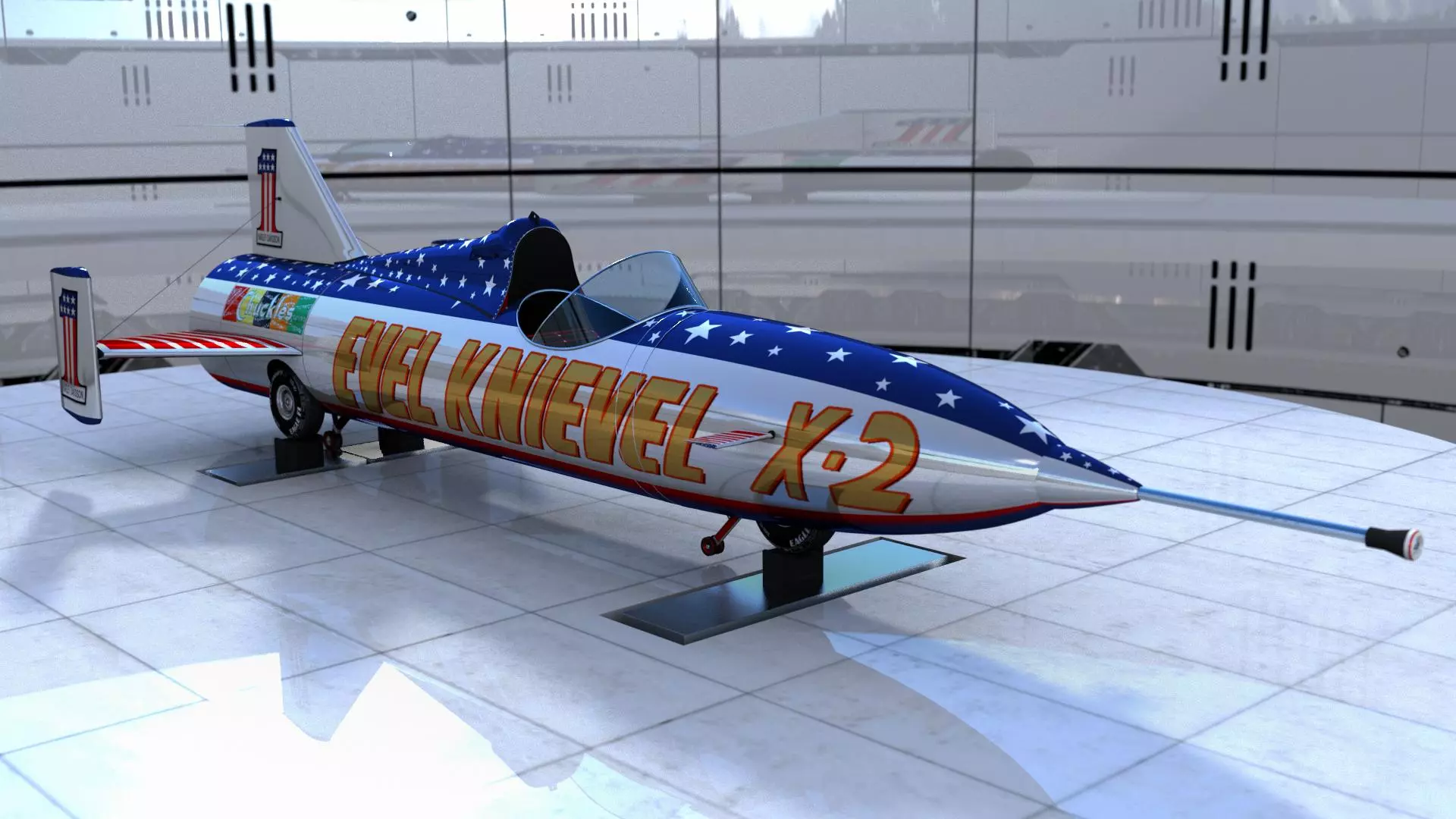

Truax took over for the second design, the X-2, which was essentially a 13-foot rocket with an Evel-sized open-air cockpit, and three vestigial wheels installed basically just to get it up the ramp, which would be set at an extreme angle. All pretense that it was a motorcycle had gone out the window by this point.

Truax's rocket of choice was the steam rocket, a big, dumb, simple booster that offered adequate performance for the job while being extremely reliable. Essentially, it was a giant tank of water, heated to 468 degrees fahrenheit, and prevented from boiling off simply by keeping it pressurized at 500 psi.

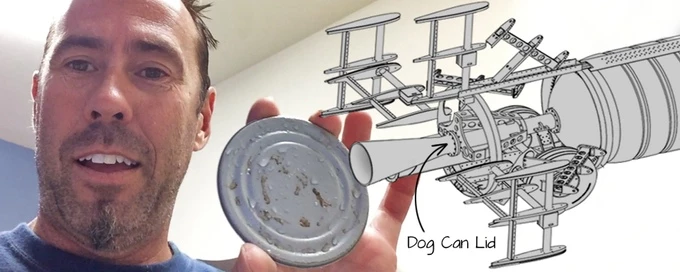

All it had to hold that pressure in was a dog food can lid at the bottom – yes, an actual dog food can lid – and when that was removed, the water within would rush out through a booster nozzle, flash-evaporating into steam and providing some 6,000 pounds of thrust in the opposite direction - enough to boost the rider to 400 miles per hour from a dead stop in less than 5 seconds, and theoretically enough to fling it three quarters of a mile downrange, or about three times as far as the canyon gap, with a maximum arc height of 2,000 feet.

Truax built three X-2 Skycycles. The first was designed to fail as theatrically as possible, so footage could be leaked to the media that would make the whole thing look like even more of a death trap than it was. It succeeded admirably, both at failing, and at drumming up a crazy level of attention.

The second was the actual test vehicle, and it was launched under total secrecy. Ominously, there was a problem with the parachute, which released early, and it fared no better than the first, tumbling 500 feet down and crashing into the river as Knievel looked on, contemplating his mortality.

But Evel always felt his word was his guarantee, and despite Truax pleading with him to run more tests, he decided the jump was to go ahead as scheduled.

By the time the day arrived, on September 8, 1974, a huge crowd had assembled at the launch site, a lot of whom were biker types and camping out. Their partying escalated to near-riot levels as anticipation built for the main event.

And although there was a 20mph headwind whipping back across the canyon, Knievel wasn't going to postpone the jump. It was on. With some 10,000 people looking on, and millions more tuned in to live closed circuit broadcasts, he made a quick speech, winched himself up into the cockpit, and hit the button.

And as the world watched, his greatest failure unfolded. The parachute deployed early - not, as some guessed, because Evel passed out from the extreme G-forces of the launch and let go of his dead man's release stick. But because of a mechanical failure, similar to what happened on the second test flight.

The rocket boosted Knievel about a thousand feet into the air, with the parachute dragging behind, and although it still took him right across the canyon at his apex, that headwind blew him backwards, back into the canyon and perilously close to the cliff face as he plummeted a mile down, bouncing off lava rocks at about 70 feet over the water, then crashing down just a few feet from the river.

Had he landed in the river, he would likely have drowned; the jumpsuit and harness he was wearing made it very difficult to get out of the Skycycle. But on dry ground, Knievel emerged, roughed up but virtually unharmed apart from a bloody broken nose. And his legend rocketed into the stratosphere in a way the Skycycle never could.

Evel Knievel died in 2007 at the age of 69, although decades of abuse and a Guinness World Record 433 bone fractures left his body looking more like a 90-year-old's. Bob Truax made it to the ripe old age of 93 and died from cancer in 2010.

Truax's dream of cheap private space transport never became a reality. Likewise, a plan to do a successful jump with Evel and the Skycycle over Mt. Fuji in Japan never happened, because Knievel beat his ex-press agent half to death with a baseball bat and ended up broke, disgraced and in jail.

And the launch site at Snake River canyon sits there to this day, a monument to a historic and heroic failure. "That canyon hasn't moved an inch," Knievel used to say, "and I don't see a long line of daredevils lining up to jump it."

He's right. It's not a long line, it's just one.

Completing the legacy: Return to Snake River

Eddie Braun is a stuntman, stunt driver and stunt co-ordinator with hundreds of hollywood credits to his name, from the original Dukes of Hazzard TV show, through to The Avengers, Sons of Anarchy and the Transformers movies.

Like many in the business, Braun holds Evel Knievel as an icon, a childhood hero and inspiration, and to cap off a crazy career, he's decided to retire with one last stunt. Braun is going to jump that Snake River canyon in a rocket bike – an almost perfect replica of the one Evel rode 42 years ago.

And who better to build it than Scott Truax, whose father built the original? Scott was just a child back at the 1974 launch, but he was there on the launchpad with his dad when it happened. Eddie and Scott are determined to complete what the last generation started.

The new bike, the Evel Spirit, has been built according to Bob Truax's original blueprints; an emotional journey for Scott, who spent many hours working with his father's original sketches, notes and calculations, as well as visiting the Evel Knievel museum in Canada where he measured "every nut, bolt and rivet" on the original test rocket. Building the Evel Spirit has been very much an exercise in walking in his father's footprints, and Truax hopes to prove his father's original design would have done the job if the 'chute didn't let go.

The new bike has some extra support structures in the nose cone to soften the landing, and it's got a more sophisticated ballistic parachute system that the pair believes will prevent a repeat of the problem that brought the Skycycle X-2 to its end. It's also got a Troy Lee Designs paint job and an official theme song – Elton John's Rocket Man, performed by Slash.

But again, it's a steam-powered rocket, slated to produce 6,000 pounds of thrust and some 10,000 horsepower as it blasts Braun upwards to 400 mph (644 km/h) in about 5 seconds. And again, to honor the original design, Scott Truax has cut the top off a dog food can to keep the pressure in before launch.

The jump is scheduled for September 17 at the original launch spot near Twin Falls, Idaho, there's a Kickstarter in effect to help defray the costs, and the whole spectacle will be webcast live around the world for viewers willing to fork out five bucks.

But that's not how I want to see it. This stirs my inner child like few other ideas. Screw it, I'm going over to see this in person. See you there!

More information: Evel Spirit