Researchers at Cornell University have been working on batteries that can 'flow' through the internal structures of robots, kind of like how blood in humans' veins powers our bodies.

The team has been exploring an idea it's calling 'embodied energy,' where power sources are organically incorporated into machines, as opposed to fitting them into compartments.

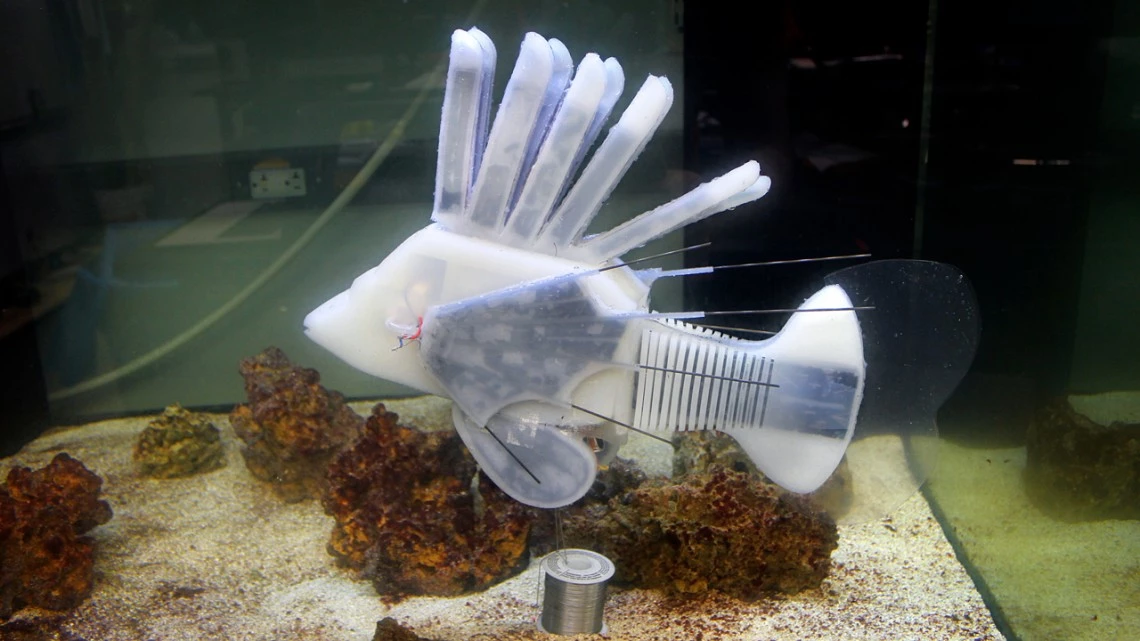

The engineers previously demonstrated this concept in a soft robot inspired by a lionfish back in 2019. Now, they've developed a worm and a jellyfish that are powered by a circulating hydraulic fluid releasing energy into their systems. Anyone getting Horizon Zero Dawn vibes from this?

How in the heck, you ask? And why go to all this trouble when every other standard-issue worm- and jellyfish-shaped robot manage just fine with regular batteries?

Good questions, both. 'Robot blood' systems can reduce the weight and increase the battery density of power sources for small robots designed for challenging applications, like monitoring ocean floors, investigating pipes, and exploring tight spaces. That means these robots can operate for longer before they need to be retrieved and charged.

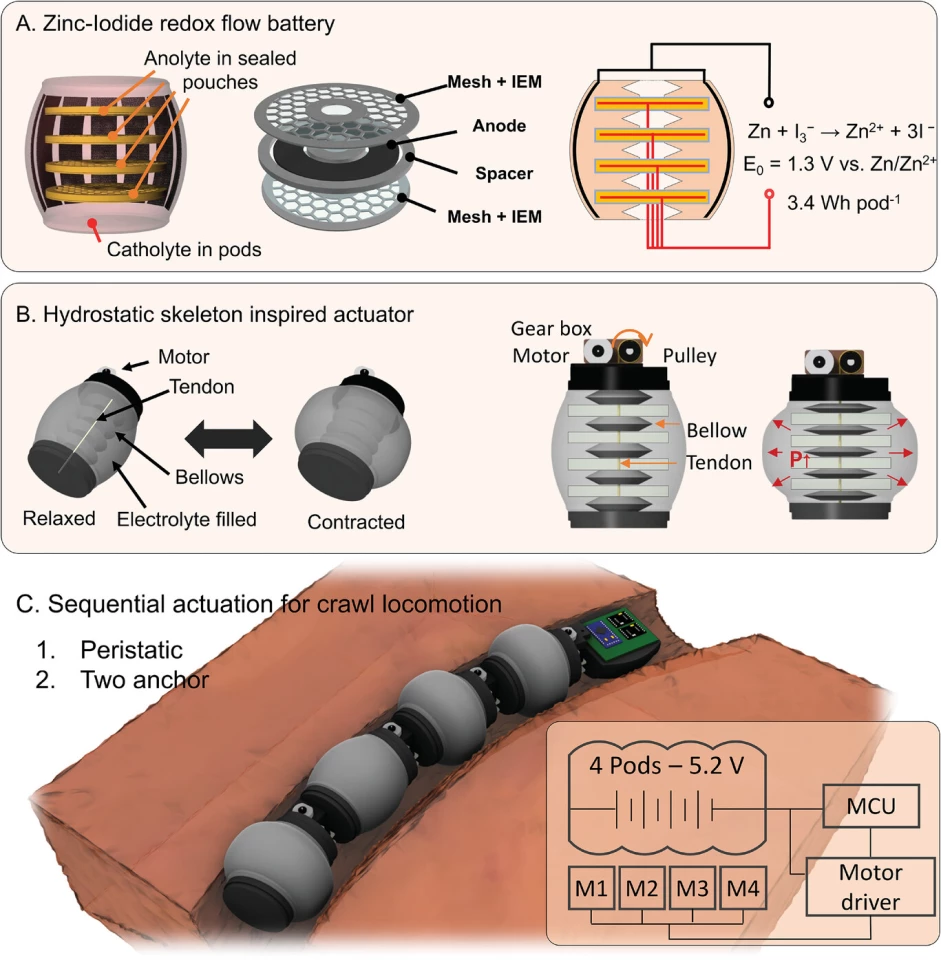

Robot blood also allows for greater mobility. Describing the worm, project leader Rob Shepherd explained, "... the battery serves two purposes, providing the energy for the system and providing the force to get it to move. So then you can have things like a worm, where it’s almost all energy, so it can travel for long distances.”

Powering the worm with a flexible battery system means the robot can inch along the ground. Its design features interconnected segments along the length of its body, each with a motor and tendon actuator. These can contract and expand to push the robot forward. It can also move up and down a vertical pipe, similar to a caterpillar.

The researchers note their worm robots are slow – covering just 344.5 ft (105 m) in 35 hours on a full charge – but they're actually quicker than other hydraulically powered ones.

The robot blood system itself is essentially uses a pair of Redox Flow Batteries (RFB). These have electrolytic zinc iodide and zinc bromide fluids dissolving and releasing energy through a chemical reduction and oxidation reaction (hence the term 'redox'). The team used this concept to build flexible batteries inside the robots that don't require rigid structures to hold them in place.

In the case of the jellyfish-shaped robot, a RFB is connected to a tendon that changes the shape of the bell at the top of its body and propels it upward through the water. When the bell relaxes, the jellyfish sinks back down. This design can operate for 90 minutes on a single charge.

The embodied energy approach could help usher in a whole range of specialized research robots in the future. To that end, Shepherd notes that the next phase in its evolution could include machines that can take advantage of skeletal structures, and walk.

Source: Cornell Chronicle