In what sounds like the opening scenes of a sci-fi disaster movie, scientists have managed to revive microorganisms that have laid dormant for over 100 million years. These microbes were discovered deep beneath the seafloor, where they’ve been slumbering since the age of dinosaurs.

The sediment samples were taken 10 years ago, during an expedition to the South Pacific Gyre. Located in the huge expanse of ocean between Australia and South America, this region is the furthest from dry land you can get on this planet.

Here, the team drilled a series of sediment cores that extended 100 m (328 ft) into the seafloor, which itself lies almost 6,000 m (20,000 ft) below the ocean surface. This area is thought to be pretty lifeless due to few available nutrients, and the researchers wanted to find out.

“Our main question was whether life could exist in such a nutrient-limited environment or if this was a lifeless zone,” says Yuki Morono, lead author of the study. “And we wanted to know how long the microbes could sustain their life in a near-absence of food.”

The team found oxygen in all of the cores, meaning that if this sediment forms slowly oxygen could filter all the way down. This could potentially support microbes that require oxygen to live, even for millions of years. To find out, the researchers incubated some of the sediment samples, providing plenty of nutrients.

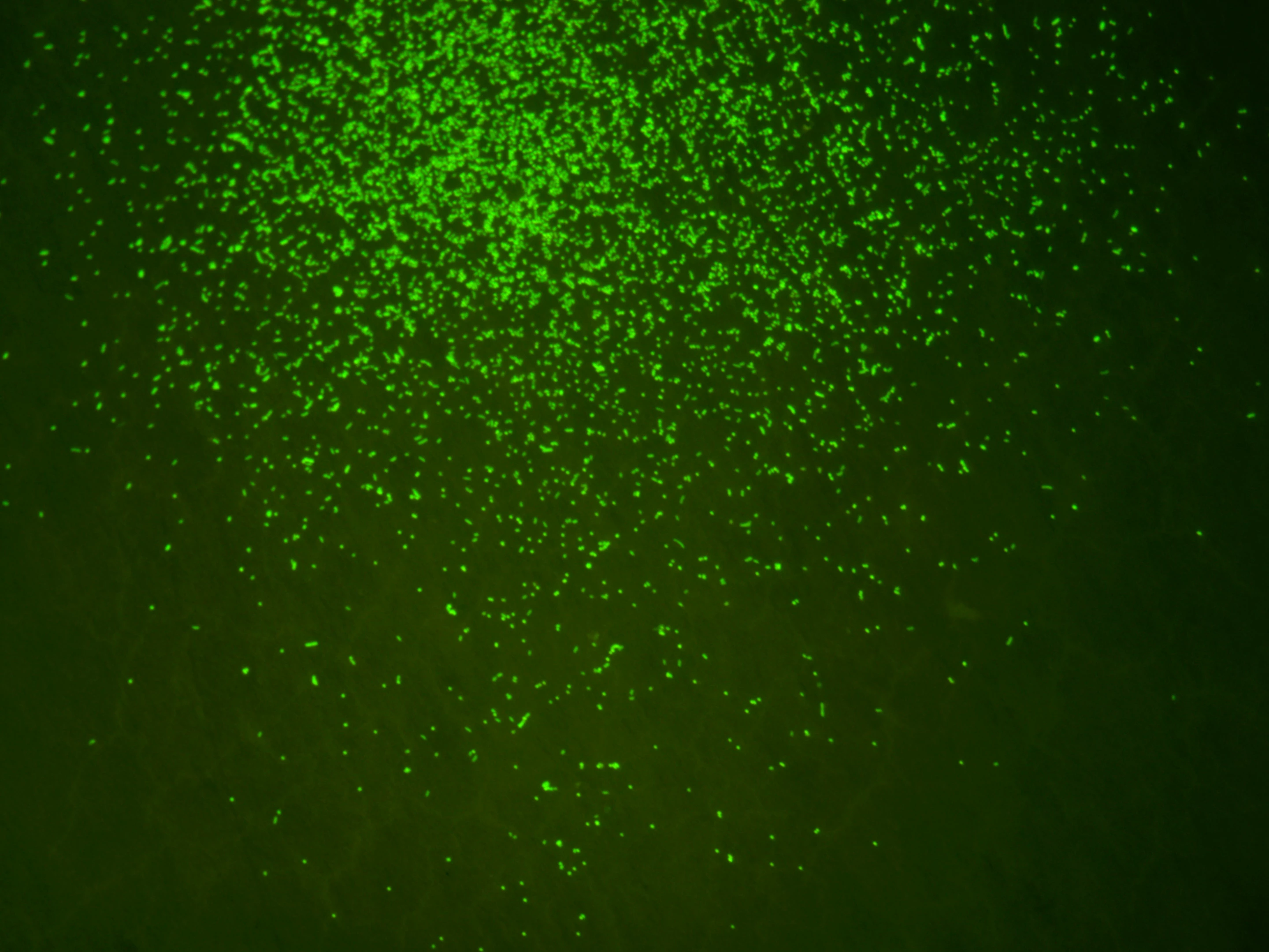

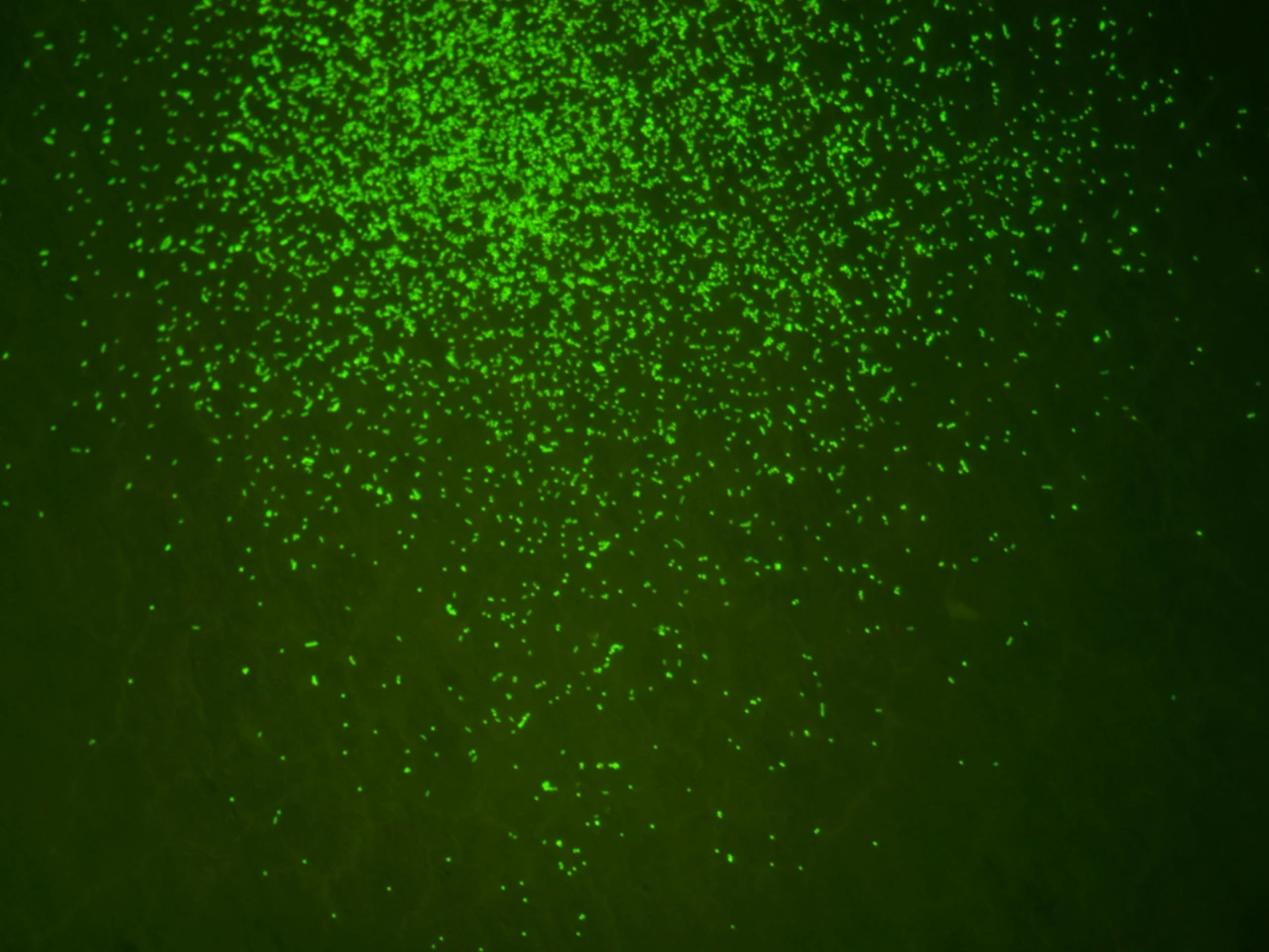

Sure enough, the ancient microbes began to stir. And not just a few – it was almost all of them, even the oldest specimens. The team found that 99.1 percent of microbes dating back to 101.5 million years ago were still alive, and started eating when food became available.

“What’s most exciting about this study is that it shows that there are no limits to life in the old sediment of the world’s ocean,” says Steven D’Hondt, co-author of the study. “In the oldest sediment we’ve drilled, with the least amount of food, there are still living organisms, and they can wake up, grow and multiply.”

Because of the limited resources, life progresses much more slowly for these organisms. It’s unlikely that they evolve very quickly, considering that all of their very little energy goes towards just barely maintaining their existence. Other studies have found similar long-lived bacteria living as far as 5 km (3.1 mi) underground.

These microbes are, clearly, among the oldest living things on Earth, dating back to the height of the dinosaur age. They easily beat the oldest multicellular animal, which is a worm thawed out of the Siberian permafrost after a 40,000-year hibernation. Other microbes may have them beat though – some bacteria have been revived from spores trapped in amber for 250 million years. But since those were spores and not the bacteria themselves, you could make the argument that they don’t count in this competition. Still, it’s all pretty amazing.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: University of Rhode Island