Scientists have discovered the fossil remains of what may be the largest penguins that ever lived. The bones, found on a beach in New Zealand, belonged to a giant bird that was more than three times the size of the biggest living penguins today.

We often associate the distant past with gigantic animals, for good reason. The era of the dinosaurs saw the largest-ever animals on land, in the skies and possibly in the seas, and later, huge versions of modern creatures like sharks, otters, turtles and ostriches roamed the Earth.

Now scientists have added another animal to the list – penguins. Fossil bones found on a beach in Otago, on New Zealand’s South Island, were attributed to a previously unknown species, which has now been named Kumimanu fordycei. It lived between 55 and 60 million years ago, placing it just after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

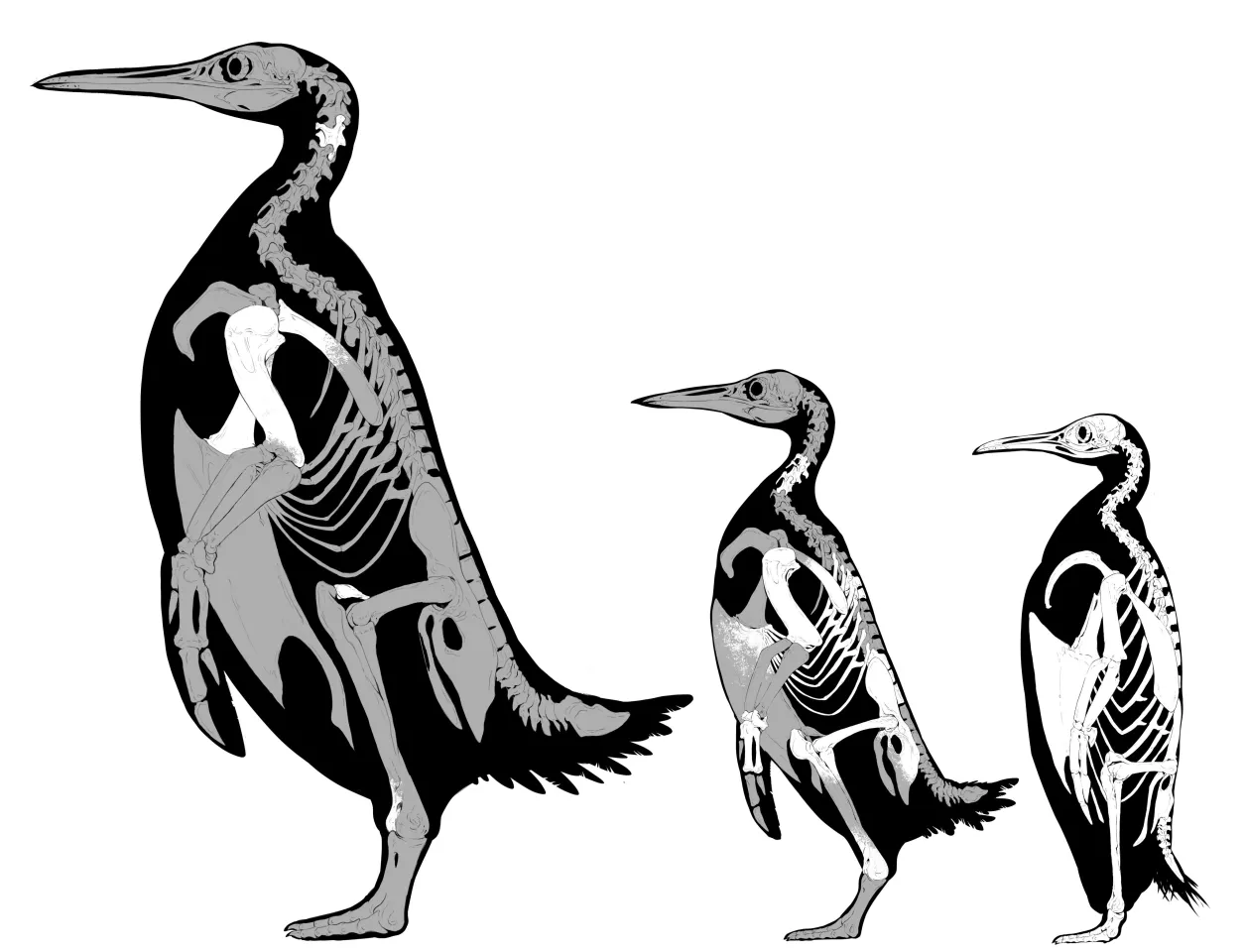

By creating digital models of the bones and comparing them to other fossils and living penguins and other semi-aquatic birds, the team was able to estimate the size of the ancient species. They estimated that it would have weighed around 154 kg (340 lb) – by comparison, the largest living species, the emperor penguin, tops out at about 45 kg (100 lb).

That also makes K. fordycei much larger than known extinct giant penguins like the related Kumimanu biceae, which was found in the same region and dates back to about the same time period. The latter is estimated to have weighed a little over 100 kg (220 lb).

The researchers haven’t officially estimated how tall this new species would have stood, however. That’s because different penguin species have different proportions and postures, and there wasn’t enough of the skeleton found to make that call.

The team also discovered another new species of extinct penguin from the same time, which they named Petradyptes stonehousei. This one weighed in at about 50 kg (110 lb), making it a little larger than today’s emperor penguin.

The fossil finds allow scientists to reconstruct the evolutionary history of penguins. Obviously, the animals grew very big very early in their history, and the team says this likely would have allowed them to dive deeper than their modern counterparts, and could have helped keep them warm in cold waters.

The research was published in the Journal of Paleontology.

Source: University of Cambridge