The sooner a farmer knows that their crops are suffering, the faster they can take action to prevent major crop failure. A new plant-leaf-poking sensor could soon help them do so, by sending an alert as soon as the plant gets stressed.

Plants of all types continuously produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as part of natural processes such as photosynthesis and respiration.

They produce higher amounts of the chemical when they're stressed, however, as a means of sending signals between cells in order to activate their defense mechanisms. Stressors causing this reaction can include drought, pest damage, and infections.

While there are methods of detecting elevated H2O2 levels in plants, most of them involve removing a leaf, taking it back to a lab, then subjecting it to a multi-step analysis. There are also optical devices that gauge H2O2 concentrations based on how a plant fluoresces, but they can be thrown off by the plant's chlorophyll content.

That's where the new sensor comes in.

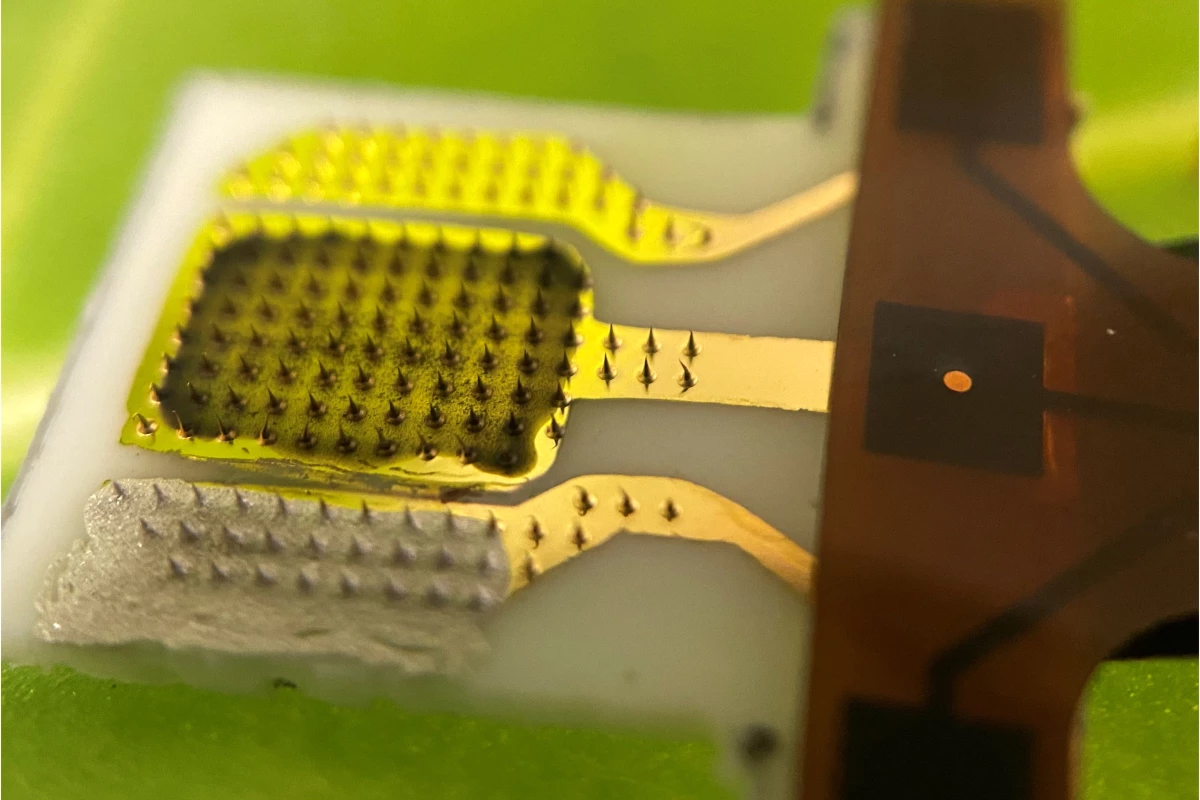

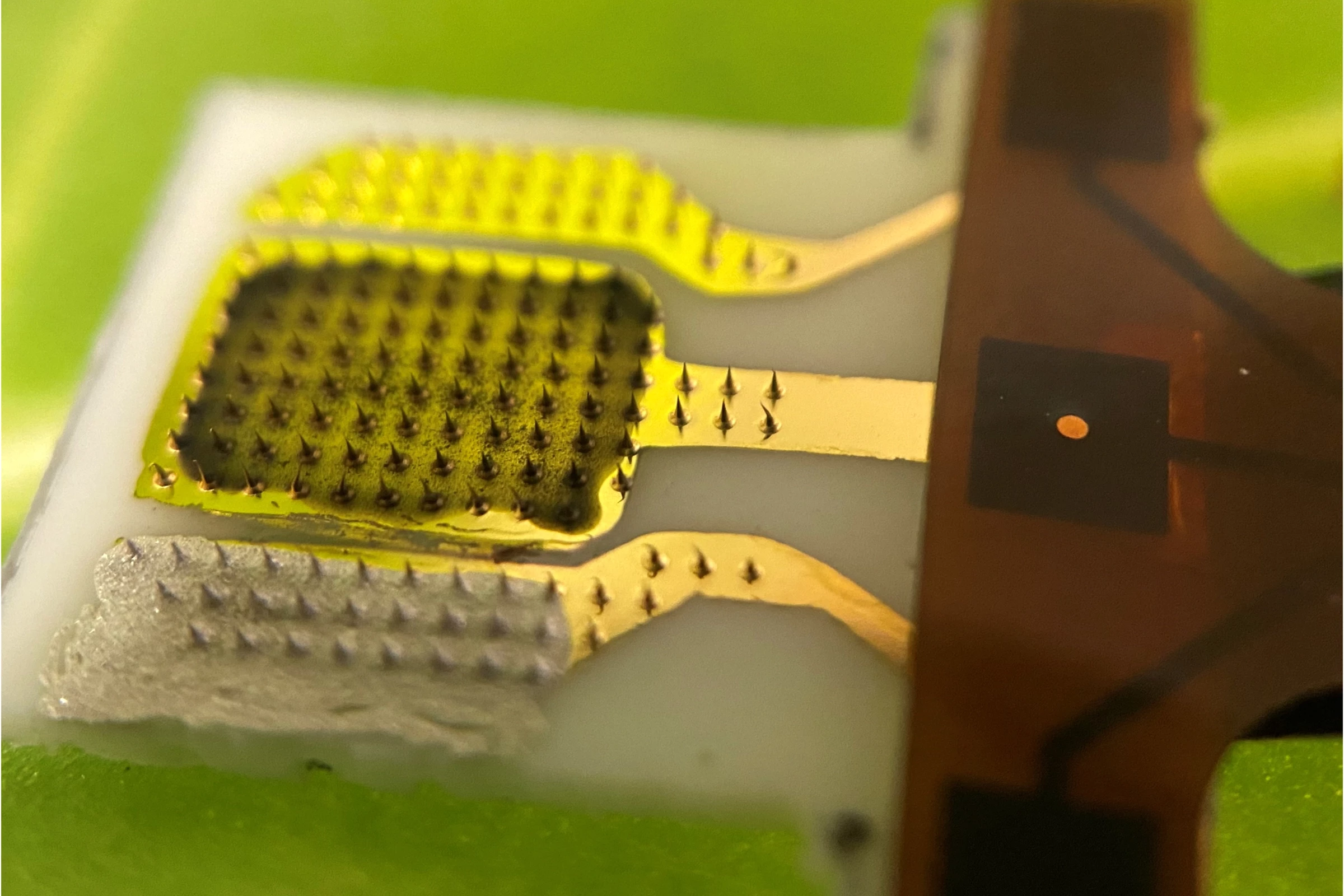

Developed by Prof. Liang Dong and colleagues at Iowa State University, it takes the form of a flat, flexible polymer patch with array of tiny gold-coated "microneedles" along its underside.

That side is additionally coated with a hydrogel made up mainly of a bio-based material known as chitosan. The gel also contains an enzyme that reacts with hydrogen peroxide to produce electrons. A third gel ingredient, graphene oxide, causes the electrons to flow between electrodes in the sensor, producing an electrical current.

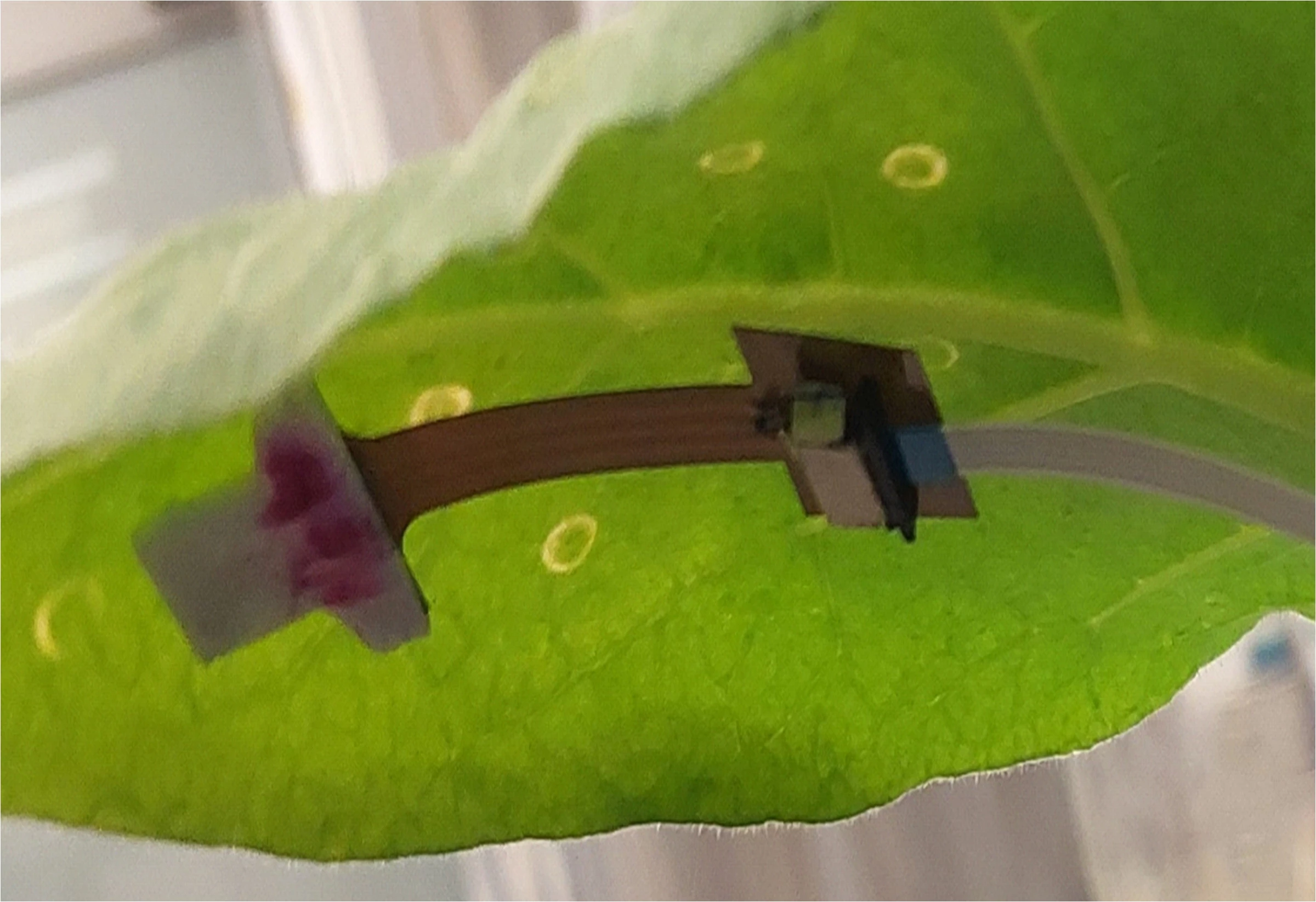

When the device is pressed onto a plant's leaf, the microneedles harmlessly pierce the very top layer of tissue, coming into contact with the sap contained within. The greater the amount of hydrogen peroxide that is present in that liquid, the greater the number of electrons produced, and thus the stronger the measured electrical signal.

If that signal is strong enough to indicate that trouble is brewing, a hardwired battery/electronics module will send an alert to the farmer's mobile device via Bluetooth, or to their home computer via Wi-Fi or existing wireless networks.

In tests performed on soybean and tobacco plants, the sensor was able to differentiate between healthy plants and those that had recently been infected with the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. What's more, the H2O2 levels indicated by the device matched those measured by traditional chemical analysis.

"The sensor can be used in different ways," Dong tells us. "One approach involves the farmer applying the sensor to a plant leaf for a one-time, on-the-spot reading across multiple plants. Another approach is to attach the sensor to several sentinel plants for continuous monitoring for several days or weeks. The current version of the sensor allows for several insertions into plant leaves, and further improvements will be made to extend its reusability."

A paper on the study was recently published in the journal ACS Sensors.

And no, this is not the first leaf-mounted plant stress sensor we've seen. Previous examples, that work by a variety of different means, are being developed by scientists at Tohoku University, North Carolina State University, and MIT.

Source: American Chemical Society